UT students describe impact of triggering language on healing process

December 5, 2021

Content Warning: This story contains mentions of suicide.

A senior in high school, Hannah Tyler called her dad to talk about college applications. They did what they always did when they spoke: laughed, joked, found humor in any situation. Three days later, Tyler’s father died by suicide.

“There’s a lot of guilt and a lot of shame that comes with suicide,” the human development and family sciences junior said. “It’s hard to not blame yourself … for not being there for someone enough, or what (you) could have done differently.”

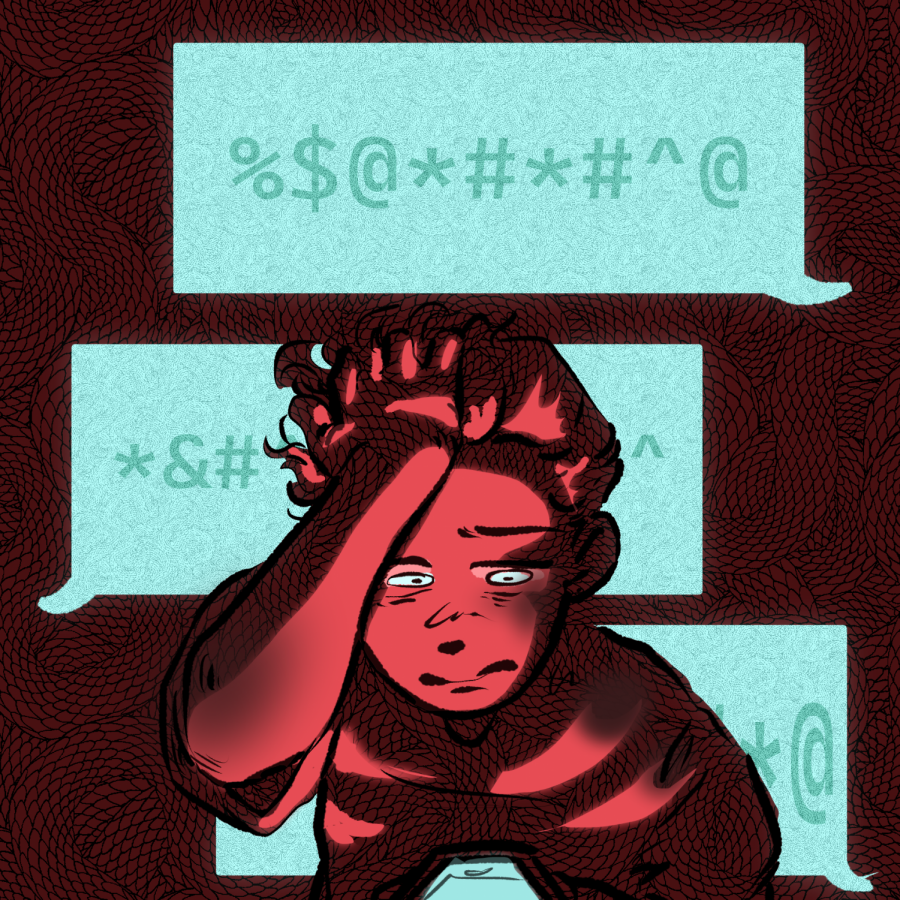

Some UT students say their peers normalize harmful language concerning suicide. With suicide being one of the leading causes of death in the U.S., this kind of language affects many, especially those who’ve personally dealt with the matter. This language hinders the healing process for many UT students.

After her father’s passing, Tyler frequently noticed this language more within her daily life, hearing and reading acronyms such as “kms” which represents “kill myself.”

“Since the day that my dad died… (hearing) those acronyms… it’s a terrible feeling,” Tyler said. “It’s an issue with everyone, I think. If someone’s struggling with suicidal ideation and they’re crying out for help, you want to be there for them and be able to help them. You can’t joke about it.”

Deisy Velazquez, a textiles and marketing senior, lost her grandfather to suicide when she was 10-years-old, and the impact of his loss still follows her to this day.

“I can talk about (my grandfather’s death) now, and it doesn’t hurt like it used to when I was younger, but it’s still very triggering for me,” Velazquez said. “It’s something that I don’t think I’ll ever be able to process correctly.”

Since her grandfather’s passing, Velazquez said the suddenness of death scares her. Carrying the weight of this loss with her, she said it upsets her to hear people normalize jokes about suicide when she suffered a loss from it.

“It terrifies me because if someone can talk about death that lightly you never know what they can do, especially if they’re going through mental health issues,” Velazquez said. “When I hear (suicidal language) I get very scared. It breaks my heart, (and) it’s very traumatic.”

This past summer, theatre junior Saylor Dement suffered the loss of her cousin at the hands of suicide. She said losing someone close to her unexpectedly caused emotional difficulty. It took a lot of effort for her to process her emotions while remaining aware of what her cousin dealt with.

Dement and Tyler met last spring through a shared spirit organization, and the two discussed Tyler’s story. Dement learned how to reconstruct her language concerning suicide, which later helped her narrate her loss and heal. She said Tyler taught her to practice more empathy and sympathy throughout her own personal experience.

“I almost got a precursor-like explanation of how not to grieve,” Dement said. “You have to be mentally aware of the person who’s gone and then your own emotions. It made me more emotionally intelligent, talking with Hannah, because I had a different outlook than I might have had without that conversation.”

Normalized suicidal language leaves Dement feeling disheartened. She understands a lot of people don’t know the detriment of this harmful language, so she encourages people to call others out when they hear language like that.

“Even if it’s an awkward conversation, you’re still doing (a) good (thing) and changing somebody’s perspective,” Dement said. “Not everybody’s going to completely change and update their vocabulary, but at least you’ve put that seed in their mind to be planted and it’s gonna grow.”