UT researchers advance carbon capture technology

December 14, 2021

Editor’s Note: This article first appeared as part of the October 12 flipbook.

UT researchers discovered a way to store 200 times more carbon dioxide from the atmosphere in deep-sea technology, which can help mitigate climate change.

The research team, which partnered with ExxonMobil in 2018 to improve carbon capture technology, pressurized water and carbon dioxide to form hydrates which will then be stored in ocean beds rather than be released into the atmosphere, researcher Aritra Kar said.

Additionally, researchers found in August that by adding magnesium to reactors that create the hydrates, they were to capture carbon dioxide 3,000 times faster than current methods.

“If I just keep carbon dioxide and water inside the reactor and pressurize it and put the temperature something close to zero it will probably start forming in about an hour or even in days,” Kar said. “With magnesium what we achieved was we could reduce this time from hours and days into just minutes.”

Current carbon capture technologies require specific geological formations that can be used to inject carbon dioxide into, but not all areas have access to these formations. Hydrates can be stored in any deep-sea ocean floor, which most countries have access to.

“The idea is to not let them escape,” Kar said. “The idea is to try to grab (carbon dioxide) and (trap) them somewhere else, so that they do not go into the atmosphere and cause global warming.”

The researchers and ExxonMobil filed a patent for their discovery in July and are looking toward pursuing further research to demonstrate its potential at a larger scale, Bahadur said.

“One of the major challenges is that we need to demonstrate this at much larger scales than what we are doing currently,” Bahadur said. “Right now we form hydrates in test tubes, but eventually we want to form a roomful of hydrates.”

This research is part of ExxonMobil’s $15 million investment to the University’s Energy Institute in 2016 in hopes of pursuing technologies to help reduce the environmental impacts of carbon emissions. The investment was made with the specific aim of further developing carbon storage technologies.

“We are exploring options for what this technology could look like five years down the line, and how we could end up commercializing it,” Bahadur said.

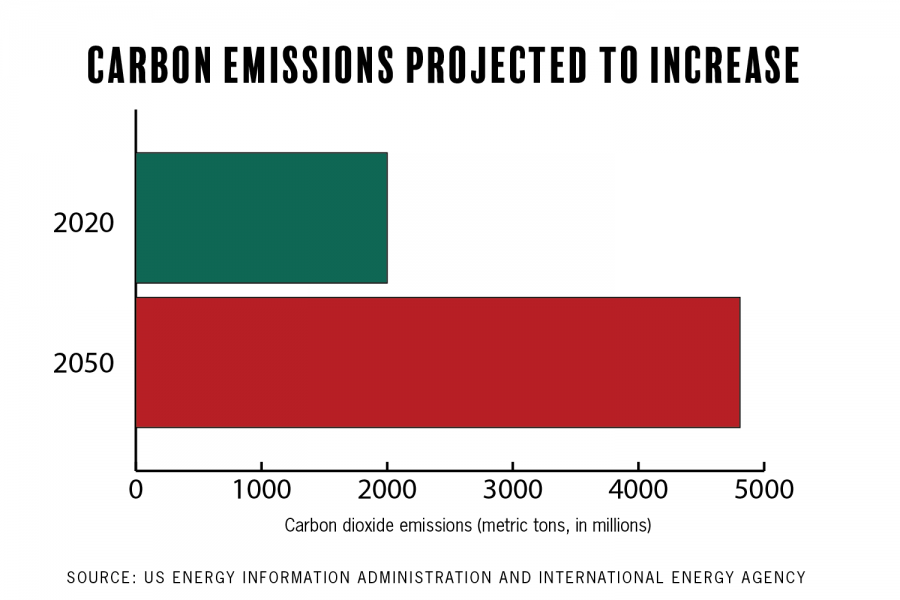

In 2020, carbon emissions fell 5.8% as a result of the pandemic, according to the International Energy Agency. However, according to the European Commission, a downward trend must persist in order to reach the Paris Climate Agreement’s goal of a 1.5 degrees Celsius limit to global warming by 2050.

“It’s extremely important to do this kind of research because where we’re at now with the climate system, we’ve put out so much into the atmosphere that even if we stopped emissions now, we (would) not stop warming,” geology professor Camille Parmesan said. “If you create a stable solid form of carbon, then that is a way of completely taking it out of the system.”