UT study shows how Mars’ surface was formed

December 14, 2021

Editor’s Note: This article first appeared as part of the October 12 flipbook.

UT researchers recently discovered that, over the span of weeks, massive Mars flooding carved out canyons hundreds of meters deep. The researchers’ new study shows how water can potentially interact with land on different planets.

While water erosion on Earth occurs over hundreds of years, the study published in September found Mars’ crater lakes stored significant amounts of water that rapidly eroded the valleys of Mars billions of years ago, said Alex Morgan, research scientist at the Planetary Science Institute. This discovery shows how other planets might interact with water differently than Earth.

“The fact that Mars’ topography is dominated by these impact craters leads it to a scenario where it can very easily pond and store lots of water that can then fill up and breach to form these catastrophic floods,” said Timothy Goudge, an assistant geological sciences professor.

Goudge said Earth’s surface is primarily affected by the movement of plate tectonics, while Mars’ surface changed due to the movement of flood waters.

“When it comes to trying to understand what’s going on on exoplanets and other solar systems … there’s a number of ways that water can affect the surface of a planet,” Morgan said. “On Earth where it’s over a long period of time, things are kind of in equilibrium … but on Mars … you’re gonna have a lot more catastrophic action.”

The team conducted the study by going through an existing catalog of Mars’ valley systems and categorizing every valley into whether or not it stemmed from a lake, Goudge said.

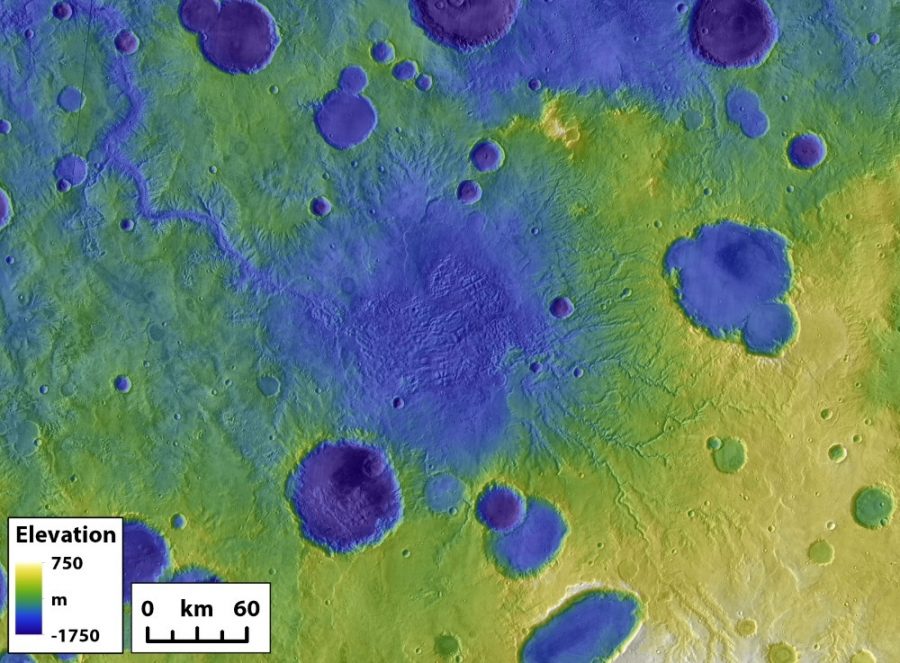

“Then we used a … global topographic map of Mars from which we could extract the volumes of these canyons, (and discover) how big are all of these canyons of valleys,” Goudge said. “Then we summed it up over the entire planet and got a final number of … the total volume of erosion from prolonged valleys versus from lake breach floods.”

Goudge said the water from these floods is currently either encased in ice, lost to deep space as a result of Mars’ weak atmosphere, or incorporated into minerals in Mars’ crust.

However, there is debate regarding how much water was lost.

“So, the most obvious reservoir of water is actually ice on Mars. So there’s a huge amount of water still on Mars: it’s just all ice. It still exists, but it’s locked up in like polar ice caps, and in fact there’s enough ice on the surface of Mars today to easily fill up all of the lakes that we studied,” Goudge said.

The team plans to continue this research through computer modeling to reproduce the lake breach flooding and examine how flooding affected specific regions of Mars.

“The next step would be to find a few case studies to understand the dynamics, and what happened as these outreach floods occurred,” Morgan said.