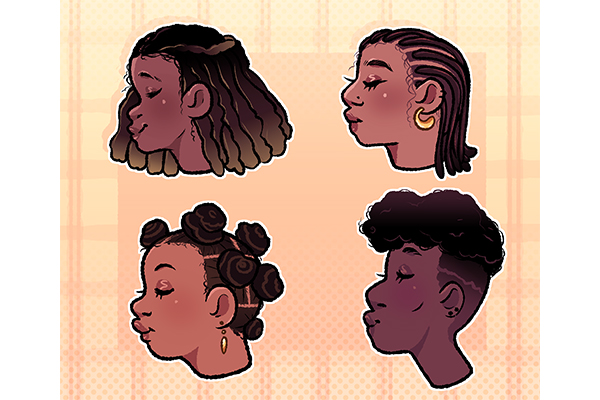

Students of color reflect on the impact of eurocentric beauty standards

December 15, 2021

Editor’s Note: This article first appeared as part of the November 30 flipbook.

Staring back at their reflection through the mirror, Angel Coleman took the last glimpse of their heat-damaged, stick-straight hair.

Straightening their hair for as long as they’d remembered, they didn’t know the last time they saw a curl on their head. So they shaved it all off. Taking in their freshly shaved head, Coleman couldn’t help but question what they’d just done.

“I was embarrassed to let other people see me because I was convinced (my hair) didn’t look good,” the radio-television-film sophomore said. “Through that process of figuring out how to like it, I slowly became more comfortable with myself.”

Eurocentric beauty standards, or the preference for light-skinned, skinny, straight-haired figures, disproportionately affect people of color’s self-image. Many UT students of color have struggled with colorism and unrealistic images of beauty since their youth, harming their self-perception and self-confidence. Now they share how they fight against these societal pressures.

With their family coming from various racial backgrounds, Coleman said the way beauty standards applied to them depended on what side of their family they were around.

“In Black communities, I (was) praised,” Coleman said. “I was constantly told I have beautiful hair and stuff like that, but from a Hispanic point of view … I would be ridiculed for being dark or for my Black features.”

After shaving their head, Coleman said they started reconstructing their ideas of beauty. In the moment, they did not find the process liberating, but eventually it made them more comfortable with their self-image. Shaving their head changed their perspective and gave them the ability to find themself beautiful without relating it to the way they looked.

“The easiest way to free yourself from eurocentric beauty standards is to retrain your brain to understand that (looks are) irrelevant,” Coleman said. “There’s other ways to be fulfilled in your life and to feel beautiful, that don’t involve the way you look.”

Mary Beltrán, a radio-television-film associate professor, specializes in the intersection of film and television and critical race theory. She said the beauty standards within society enforce social hierarchies and many people view attractiveness as related to qualities like intelligence, bravery and kindness.

“In fact, there’s no correlation at all,” Beltrán said. “People forget that there’s this really unfair system by which Black or dark-skinned Latinos have fewer opportunities.”

The application of beauty standards in media, Beltrán said, reinforces an unrealistic image of what people look like.

“It can lead to self-esteem problems … (for) kids who don’t fit that narrow standard of what beauty is thought of in Hollywood,” Beltrán said. “It does damage.”

The polar opposite of society’s beloved thin, small-nosed, white woman, Frida Espinosa described herself as a curvier, thick-skinned, thick-nosed Latina woman. The neuroscience sophomore said while she may pass as lighter-skinned and fall under that dimension of beauty standards, she faces pressures as a plus-sized woman.

“(Being plus-sized) has taken a big toll on my image of what beauty is,” the neuroscience sophomore said. “It put me down a lot as a child and embedded ideas in my head that if I was skinnier, more people would be my friend. I always wanted to be accepted and loved by everyone, to be appealing to everyone’s eye.”

Espinosa said the Hispanic community often talks down to darker complexions, deeming them unattractive. In hopes of appearing more attractive, Espinosa said she grew more conscious of the state of her skin and whether she appeared to be white passing.

“They’d call (my mom) names like ‘morena’, referring to her darker skin in a derogatory form,” Espinosa said. “It shifted my view and I (thought) if I stayed out of the sun, I wouldn’t get as dark as my mom, and that way I won’t get made fun of.”

Growing up biracial with both Indian and white heritage, sociology junior Kai Bovik said they faced colorism frequently. Receiving compliments on their white features led Bovik to value those parts of themself and accentuate them while rejecting the parts that didn’t fall into eurocentric beauty standards.

Navigating their transexual identity, Bovik said, allowed them to break free from these beauty standards. They understood that by physically transitioning they would no longer fall under the standard of beauty anymore.

“Leaving the realms of desirability behind when you transition makes you rethink a lot of stuff,” Bovik said. “Not only are the things that this transition brings me (things) that I used to think were bad, like body hair, facial hair, and (other) things that are deemed masculine — which (are) usually … associated with women of color — but I kind of started to see those as beautiful.”