Students, staff share experiences with ADHD during ADHD Awareness Month

December 18, 2021

Editor’s Note: This article first appeared in the October 29 flipbook.

Receiving a diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) didn’t surprise Stephanie Craven. Even after finishing high school, college and earning a Ph.D., Craven said she always felt like her brain operated differently than her peers and colleagues.

The Sanger Learning Center learning specialist said in the past, doctors primarily diagnosed ADHD in young boys who displayed a certain set of behavioral traits, while for others — those who didn’t fit the typical ADHD standard — the disorder went largely undetected.

“They were not diagnosing little girls with ADHD back then unless you were really a handful,” Craven said. “If you’re pretty obedient, (and) maybe you’re shooting off your mouth occasionally or there’s some things you do that you don’t really understand, but (if) you’re making A’s, you’re not getting diagnosed with ADHD.”

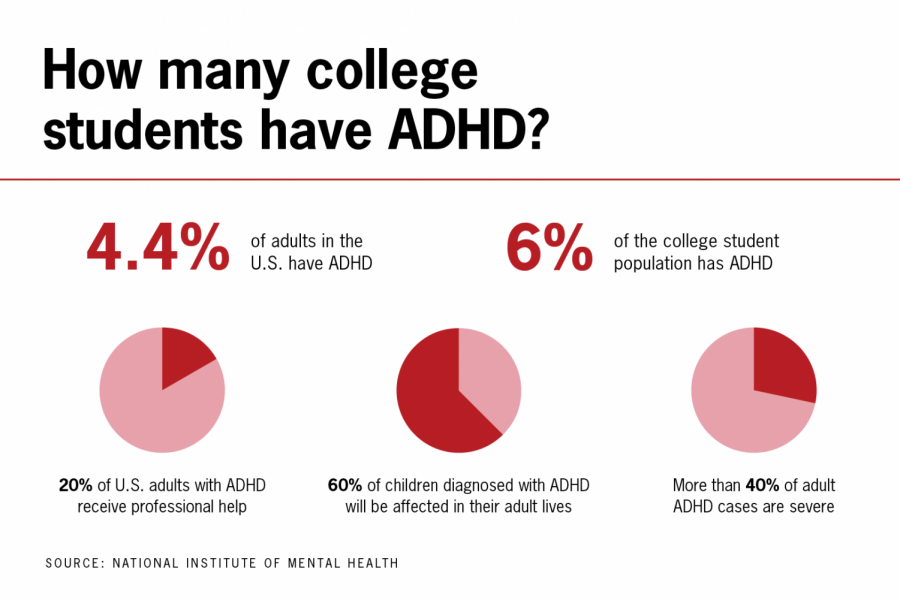

Craven, one among many UT staff and students who share an ADHD diagnosis, said living with ADHD shaped her life and impacts many others. While 4.4% of adults in the United States have ADHD, few talk about the harmful stereotypes that persist.

ADHD Awareness Month offers those who have it an opportunity to celebrate and reflect.

Throughout her college experience, Marina Newlin said she bonded with other neurodivergent students and often relied on them for representation and comfort.

“There’s this ‘neurodivergent magnet,’” the art education sophomore said. “I don’t entirely know how it happens, but we find each other and we bond over the fact that we’re just a little bit funky.”

However, Newlin said she didn’t always have a community that understood her. She was diagnosed at a young age, and harmful ADHD stereotypes caused her distress, and even ended some of her closest friendships.

“I’ve had people snap at me on several occasions because I am not looking somewhere or because I’m fidgeting with something,” Newlin said. “It’s very turbulent in a way because I’m just existing and then it’s like, ‘Stop doing that.’”

Newlin suggested neurotypical individuals ask their friends and classmates about their experience living with ADHD, so they can learn more about it and not pass judgment on them.

“If there was any one thing that I would want someone to know about ADHD, it’s that it’s a real thing that has a real impact on both my mental and physical health,” Newlin said. “But I’m not lesser because of it.”

Graduate student Lee Orfila said her experience managing stereotypes and school improved each year due to her graduate school’s flexibility, allowing her to utilize aspects of ADHD as a learning tool.

“The kind of hyperfocus and extreme levels of excitement you can get about something, if that’s the thing that you’re passionate about, can work to your benefit,” Orfila said.

Orfila’s studies involve data processing, which she said can be tedious and detail-oriented. Because she loves the subject, Orfila said she can memorize linguistics information easily and actually enjoys doing so.

“If I was looking at numbers from geology, it would just be numbers and I would hate it,” Orfila said. “But because (data processing is) an extinct sign language, I could recall almost any data point from my dataset at this very moment.”

Orfila said oftentimes, the stereotypical way people perceive ADHD consists of outward behaviors parents observe in children, like restlessness, hyperactivity and impulsiveness. Therefore, many don’t understand how ADHD actually impacts people’s daily lives.

“I think the awareness people have of ADHD is usually very externalized,” Orfila said. “It’s from this (outward) perspective of, ‘How does this inconvenience other people?’ and not necessarily, ‘How is this person really struggling or having this really difficult internal experience?’”