Flowing liquid on Mars is most likely a bunch of rocks, according to UT study

February 11, 2022

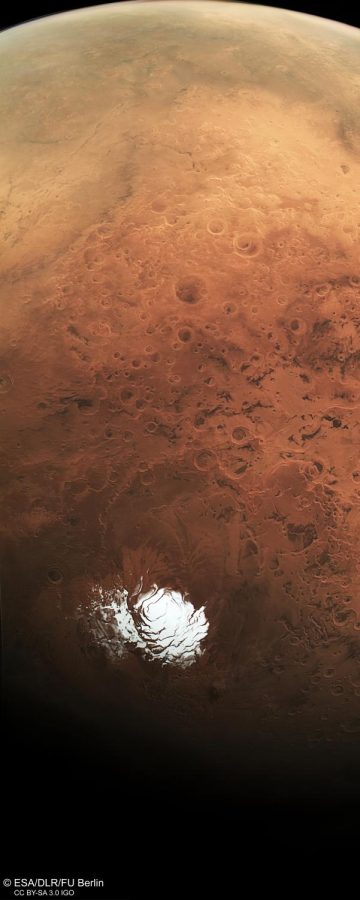

What was previously thought to be liquid water detected under Mars’ ice-covered south pole is most likely volcanic terrain, according to a study published Jan. 24 led by a researcher at UT.

Scientists first thought they were looking at liquid water when they saw bright reflections under Mars’ southern polar cap in 2018. Since then, many scientists have debated whether or not they were actually looking at water, with UT researchers exploring a new possibility for the reflections in their study. The study found that the reflections match those of volcanic plains, which is a more plausible explanation due to Mars’ environmental conditions, said Cyril Grima, a research associate at the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics and co-researcher for the study.

“Mars is dry. … It’s kind of a frozen, dusty world,” Grima said. “Today, liquid water at the surface (of Mars) cannot be sustained because of two reasons. The main reason is the pressure, (there’s) pretty little pressure on Mars, water would evaporate pretty fast. It also (has) very low temperatures, so at some latitudes, water could instead freeze rather than evaporate.”

Using known mapping data about Mars, Grima said the researchers used a model of the planet on the computer and covered it with imaginary ice sheets to see if other areas of the planet’s terrain would produce the bright reflections when covered with ice. When covered, the researchers found bright reflections similar to the ones found in 2018 under the polar cap all across the planet, meaning terrain underneath the ice caps is largely responsible for the reflection, not liquid water, he said.

Mars’ terrain likely reflects so brightly because of basalt, a volcanic rock found both on Earth and Mars, Grima said. He said previous studies showed that basalt, when rich and dense, can produce this reflective, bright radar.

Pierre Beck, an associate professor at the Université Grenoble Alpes and co-researcher for the study, said although their study found no liquid water on Mars right now, the fact that there is frozen water in the form of the polar ice caps shows that there has been flowing water in the past.

“If you want to get a taste of how much water this is, if you were to melt these two ice caps, you would have enough water to fill the Mediterranean Sea,” Beck said.

Grima said the question of liquid water on Mars is still an ongoing debate years later, especially after a different study was published the day after his, suggesting that minerals under the ice cap have water in them. Despite the two polarizing studies, Grima said he is excited to be able to contribute to this debate.

“This would have implications to understanding the volcanism of Mars,” Grima said. “Why did volcanic activity produce so much iron? It has implications to the far future of human exploration because this is a resource as well.”