UT researchers create map of Gulf of Mexico coastal plain to improve flood predictions

April 3, 2022

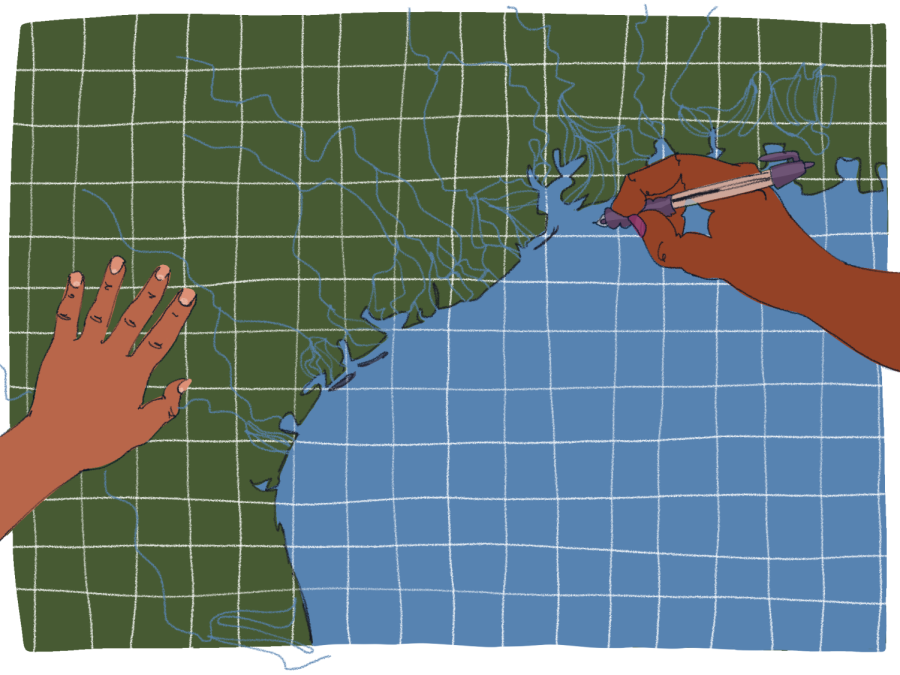

UT researchers created a map of the Gulf Coastal Plain to show how an overlooked network of water channels creates drainage pathways for floods.

Coastal plain areas are places where sediment builds up over time, eventually creating ridges of sedimentary deposits in flat terrain. Drainage basins form in between these ridges and can overflow during heavy rains. Researchers at the Jackson School of Geosciences published their findings last month that showed how the new map, created using LiDAR, light detection and ranging data, will improve flood predictions.

David Mohrig, a researcher and the associate dean for research in the Jackson School of Geosciences, said previous models for predicting flood drainage weren’t as accurate as the models created using the map by UT researchers because drainage ditches were never included.

“(With) these channels, we wouldn’t expect them to be a source of floodwaters,” Mohrig said. “There were maps of these pockets near the coast that (aren’t) connected to the really big rivers of Texas. But it wasn’t clear that there were actually smaller networks inside these areas between the large rivers.”

Using publicly available LiDAR data from state and federal agencies, the researchers mapped the network of drainage basins between the Rio Grande and Mississippi rivers, according to the study.

“(The map) allows us to do a much better job understanding where floodwaters are going on what we usually (consider) a very flat coastal plain,” Mohrig said. “It’s not that there aren’t flat areas in it, but there is more relief. And water doesn’t need a lot of relief to flow and to be routed off a surface.

Benjamin Cardenas, a postdoctoral fellow at the California Institute of Technology who was involved in the study, said other researchers observed the channels previously, but the technology did not allow them to fully map the network.

“These tend to be very vegetated areas,” Cardenas said. “So a lot of traditional ways of measuring topography, from airplanes or from orbit, just don’t work. But LiDAR, which shoots (a) laser down to the ground … is able to penetrate through vegetation.”

Cardenas said the study showed the importance of having high-resolution topographic data available to develop future flood prediction models.

“Your prediction of where floods will be (and of) where water will go is totally dependent on the quality of your topographic data,” Cardenas said. “Knowing where the channels are means that you can predict which areas will be flooded (and) which areas will be safe.”