‘Carrying the torch of health equity’

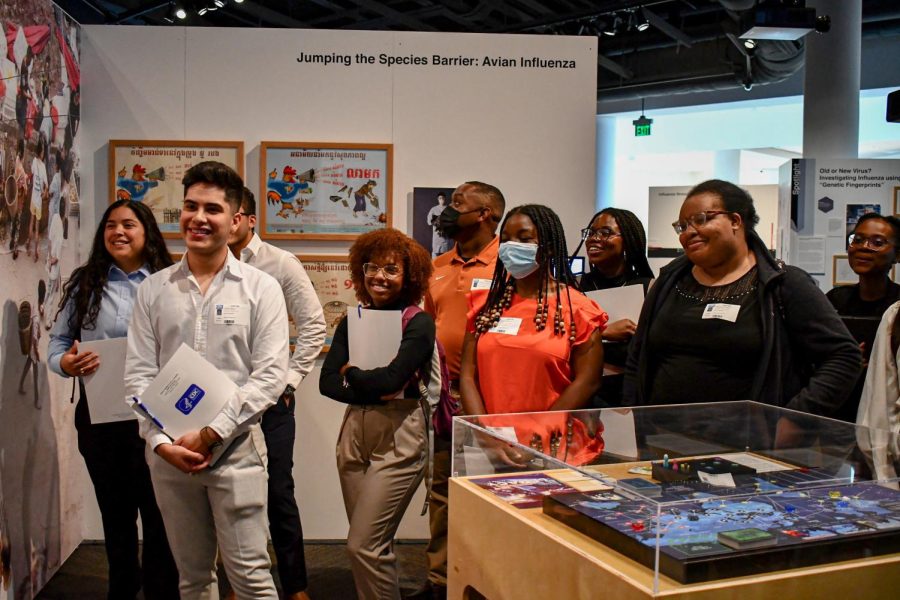

Fifteen Black and Hispanic pre-health students travel to Atlanta for the first-ever Health Equity Exposure Experience

May 3, 2022

Shaltiy-El Jackson’s lifelong love for science motivated her to pursue medicine. However, the biology freshman said she saw the lack of diversity within the field in her first year of studies.

“Whenever I would do things like shadowing or volunteering, there weren’t people that I could relate to,” Jackson said.

Black and Hispanic students make up less than 20% of Dell Medical School’s student population, according to the 2021 Texas Higher Education Board submission. In an effort to better support underrepresented student populations and promote equity in the medical field, Jackson and 14 other Black and Hispanic pre-health students visited the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta as part of the Health Equity Exposure Experience from April 27 to May 1.

“Many of us are first generation (college students), so our parents don’t really have those connections,” Jackson said. “It’s a really beneficial trip to allow us to get out there and show what we’re able to do and connect ourselves.”

Health Equity Exposure Experience

“(This) opportunity is incredibly unique — I would say once in a lifetime,” said Liliana Martinez, pipeline manager for the Office of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion for Dell Medical School. “To be a student who’s first (generation), a student of color, who hasn’t found their place, who needs to feel like they belong in a space, and to place them physically in that space is incredibly impactful.”

The program was a partnership with Dell Medical School’s Health Professions Pathway Program and predominantly funded and organized by the Division of Diversity and Community Engagement, according to Dr. Octavio Martinez, the associate chair of diversity, equity and inclusion at Dell Med.

“This program … is exactly the kind of innovation that is needed in public health,” CDC director Dr. Rochelle P. Walensky said in a video to the students in the program. “We are grateful you are a part of it, carrying the torch for health equity.”

At the CDC, students engaged with health professionals, sharing their own experiences, passion for health equity and solutions to combat medical racism.

“The value is in their lived experiences,” said Dr. Ryan Sutton, assistant dean of diversity, equity and inclusion for Dell Medical School. “We see the underrepresentation of historically marginalized groups within these spaces, so the fact that we can walk into these spaces (as) Black and brown individuals, adds a level of insight that (the medical professionals) can get.”

At Georgia Tech, the students toured the sports medicine facilities and participated in a Q&A session with members of the sports medicine staff. Here, students asked panelists about physical and mental wellness in sports medicine, various disparities within the profession and how to succeed in this field.

Throughout the trip the students were joined by notable medical professionals from the CDC, Morehouse School of Medicine and others to provide networking and mentorship opportunities. Additionally, the students and faculty went to the National Center for Civil and Human Rights as well as Martin Luther King Jr. National Historical Park.

Exploring health equity

While the trip focused primarily on students’ experiences and current disparities, historical health inequalities and the history of distrust between communities of color and the health care field were not left out of the conversation.

During the trip, Sutton pointed out a quote by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

“Of all the forms of inequality, injustice in health care is the most shocking and inhumane.”

During the CDC visit, students got to tour the museum on campus, and the guide put an emphasis on health equity dating back centuries and medical racism. During the tour, they specifically discussed the 1932 Tuskegee Experiment in which hundreds of Black men were unknowingly infected with syphilis under the false pretense that they were receiving free medical care and were never offered any treatment.

“Being a Black woman in the United States, I have seen firsthand and heard stories of the mistreatment of Black women as well as other minorities and how uncomfortable (it) can be to go to the doctor, to go to the dentist (or) any sort of medical professional,” said Bisona Yangni, a health and society junior. “I want to do what I can to help alleviate that stress from people.”

Today, disparities continue as Black women are three to four times more likely to die from pregnancy related causes than white women, according to the American Medical Association.

Black and Hispanic physicians made up approximately 11% of active physicians in the U.S. in 2018, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges. At the same time, Black and Hispanic citizens make up nearly 32% of the U.S. population, according to the most recent census data.

“When you witness the disparities within your own community, you really get to see how the system isn’t perfect,” said Ginata Lopez, a health and society junior. “When I found out about health equity and the political and social determinants of health care, it made me want to fix it and advocate for people.”

‘Will this world let me be a doctor?’

Public health sophomore Faith Folorunso said she feels excitement about her future in the health care field and sparking change within the industry. However, she said, at times, she grows weary of how realistic a future in health is for her as a Black woman, especially at UT, where she is surrounded by white classmates.

“I’m used to dreaming so big, but there’s always the fear of my color not allowing me to fulfill my dreams, based on how I see the world treat minorities,” public health sophomore Faith Folorunso said. “I want to be a doctor, but will this world let me be a doctor?”

According to the 2021 Texas Higher Education Board submission, Dell Medical School student population is nearly 60% white. In comparison, approximately 47% of the total medical school student population across the country in 2021-2022 is white, according to data gathered by the Association of American Medical Colleges.

Sutton and Dr. Steve Smith, associate dean for student affairs, speaking for Dell Medical School, said that the issues within the school causing these disparities in race are a result of systemic barriers, and they are trying to start conversation about working to improve it.

Several trip attendees said they feel imposter syndrome within being racial minorities in pre-health spaces because of the lack of diversity they see around them.

“Those national numbers have remained stagnant for several decades, despite multiple initiatives from national, local and governmental organizations,” Smith said. “Unfortunately this problem has systemic roots, but our admissions are moving closer to what those demographics should be.”

Additionally, Dell Medical School fosters programs like a recent one in which racial minority students are placed in mentor groups with local physicians from diverse programs, or numerous student organizations aimed towards supporting and creating a safe community for underrepresented minorities. Sutton said this initiative acts as both a temporary solution for a much larger issue and the tentative beginning of more efforts to prioritize diversity, equity and inclusion.

“We have work to do,” Sutton said. “There is a diverse, talented and gifted pool of future health professionals seeking admission into medical schools across this country. As we continue to seek to improve diversity in representation, we must continue to examine our procedures, policies and practices to ensure they are equitable and inclusive.”

Future of medicine

“I’m hopeful that things (in the medical field) can look different and that people will start to see the wrongdoing, especially people who aren’t minorities,” Jackson said.

Several students said this trip reignited their love for medicine, public health policy and health equity advocacy. Throughout the course of the trip, multiple professionals referred to the students as the “future of medicine.”

“You get to have an impact on these professionals that are already established in the field and offer them a sense of your experience (and) what you feel the health care industry needs,” neuroscience junior Diobenhi Castellanos said. “That’s really impactful because high school me would never (have thought) I’d ever be given an opportunity like this.”