UT art class increases students’ empathy

July 11, 2022

A professor within the Department of Art and Art History and a Dell Medical School professor found that art can improve people’s empathy for cancer patients in a recent study.

“Aesthetics of Health: Art Pedagogy Meets Community Engagement,” a visual art class taught each spring since 2021 by Megan Hildebrandt, associate chair of UT’s art and art history department, exposes students to different lived cancer experiences through guest speakers. Some speakers have cancer themselves, and some have loved ones with cancer; their testaments help guide the students’ art.

Hildebrandt, a young adult cancer survivor, said she collaborated with Robin Richardson, assistant director of care delivery transformation and community engagement at Dell Medical School, to quantitatively measure the changes she noticed in her students. Through the Toronto Empathy Questionnaire, which scores people’s empathy on a 64-point scale, they found that students’ empathy scores increased by nearly three points to 55.38 after taking the class.

“I had been noticing in previous iterations of the class … the students’ work seemed to get better on a conceptual level,” Hildebrandt said. “Robin (Richardson) suggested, ‘I think we could actually see if their empathy scores (get higher) using the Toronto Empathy Questionnaire.’”

Graduate student Nicholas Wong said taking the class helped him connect with cancer patients on a deeper level.

“I feel like part of the empathy came through the semester-long process of getting to know someone in a very low part of their lives and doing our best to relate to them as they’re going through treatment,” Wong said. “It’s very humbling to see these people open up to a class of students and artists.”

Throughout the course, eight different speakers spend 45 minutes sharing whatever they choose with the class. While they listen, students create a portrait of the speaker and share their art once the presentation is done. Studio art senior Bee Cortez said they were able to empathize more with the speakers after creating the portraits.

“My experience was extremely vulnerable … because my experiences within the healthcare system are also not super (positive),” Cortez said.

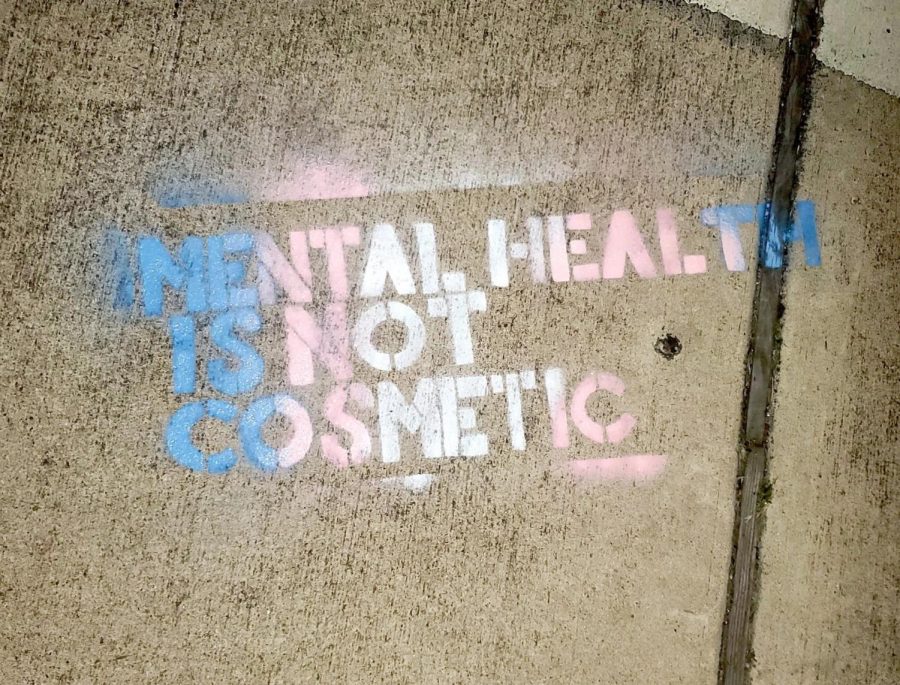

Cortez said Hildebrandt encouraged them to explore their own relationship with the healthcare system as a transgender person. This allowed them to create art based on their experiences. As part of the class, Cortez created a piece titled “Mental Health Is Not Cosmetic,” which addressed an Arkansas bill that classified gender-affirming surgeries as cosmetic surgery and outlawed it for minors.

“One of the things I’m extremely passionate (about) is trans rights,” Cortez said. “We got to ‘Mental Health Is Not Cosmetic’ because your mental state and your state of mind as a trans person, how you see yourself, your own levels of body dysphoria — it’s a lot deeper than just a cosmetic process or surgery.”

Hildebrandt plans to teach the class each spring. Wong, who graduated with a Bachelor of Fine Arts and is currently pursuing a master’s degree in nutritional sciences, said combining art and research in this way is beneficial to all parties.

“When two disciplines collide with the same goal, I feel like I can walk away with something new and generative,” Wong said. “As artists, I think it is very beneficial to be exposed to something like an oncologic clinical space. And as a doctor, I feel like there’s so much to learn by the mind and empathy of an artist as they treat their patients.”