UT astronomers find new distant galaxy with James Webb Telescope

August 23, 2022

Using the James Webb Space Telescope, the largest optical telescope in space, UT astronomers along with researchers from other institutions have discovered a galaxy formed roughly 300 million years after the Big Bang.

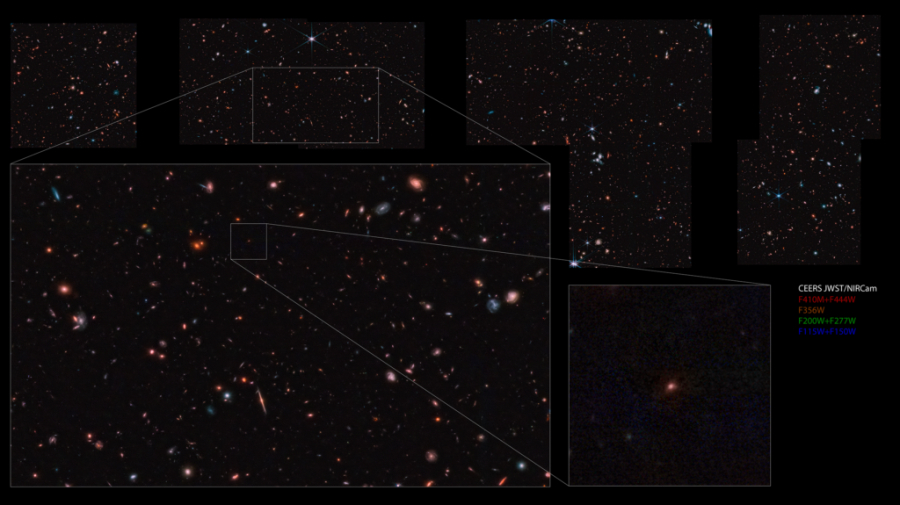

Led by Steven Finkelstein, an associate professor of astronomy, the Cosmic Evolution Early Release Science Survey team released photographs from the telescope depicting what could be one of the oldest galaxies ever discovered. Principal investigator Finkelstein said his team used the telescope’s wide range and depth of field to identify the never-before-seen galaxy, which he named Maisie’s galaxy after his daughter.

“(This) galaxy stuck out to us as the most distant one that we think we found that was still pretty bright,” Finkelstein said. “It’s possible there may be other more distant galaxies in there that are a little fainter and need more time to study.”

The discovery is currently not published in any peer-reviewed journals, but if approved, Finkelstein said the finding would mean the universe began forming complex galaxies much earlier than scientists initially thought.

“After the Big Bang, it took time for stars and galaxies to form, ” Finkelstein said. “We call that time period the Dark Ages. We don’t know when the Dark Ages ended — it could have been really rapidly, or it could have taken quite a long while. By seeing pretty bright, decently big … galaxies only 380 million years after the Big Bang, it’s very likely that the Dark Ages ended much sooner than that.”

Astronomy postdoctoral student Micaela Bagley said the telescope was more powerful than the team expected.

“This telescope has been in the works for decades, and most of us on the team have been heavily focused on preparing for it for the last four or five years,” Bagley said. “We’re just so excited about how amazing the images are and how much we can learn there.”

The telescope uses a larger mirror and is optimized for infrared light, making it easier to identify distant galaxies, Finkelstein said.

“We were not able to see into the early universe with (the Hubble Telescope) because we couldn’t see relevant wavelengths of light,” Finkelstein said. “That is what (the James Webb Telescope) is optimized to do.”

Astrophysics doctoral student Rebecca Larson said the team will continue to survey the same area in December when the observational field is visible again.

“What we have right now is less than half of our entire full program; this is still not even half of everything that we’re doing with this one program,” Larson said. “(These images) that we released (were) four of our NIRCam images out of 10 total, so we will continue to fill out our field.”

Finkelstein said after the mosaic of the team’s work is completed in December when they take more photos of the sky around Maisie’s galaxy, the team will use a different telescope tool called NIRSpec to study the compositions of galaxies.

“Essentially you take the light from a galaxy, you split it apart into its component colors, and by studying that spectrum, which is what we call the rainbow, we can learn about the chemical compositions of stars, how hot the stars are, things like that,” Finkelstein said. “That is always much more powerful and more informative than just images alone.”