Banned Books Week puts censorship on front page, students weigh in

September 20, 2022

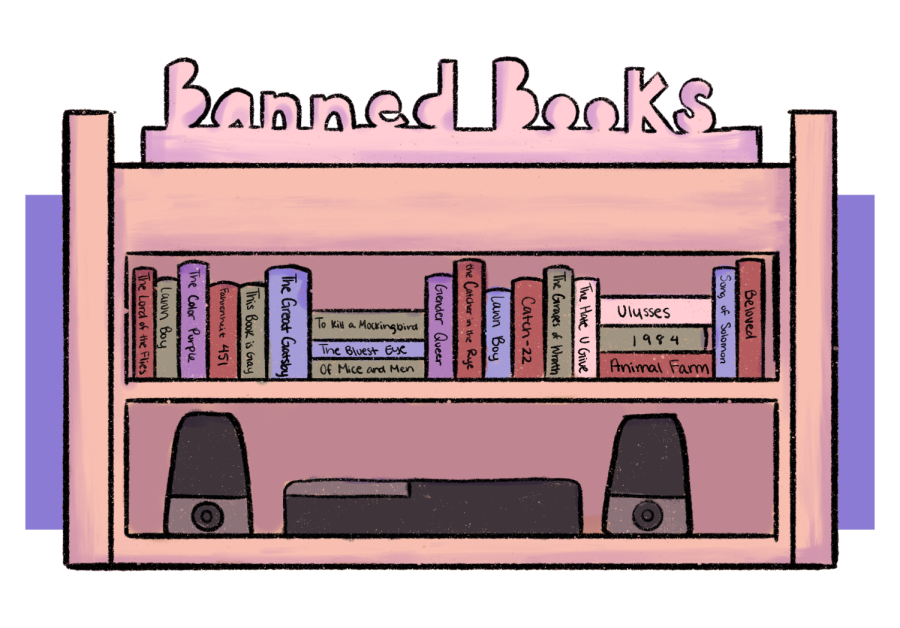

One thousand one hundred and forty five book titles by 874 different authors, 198 illustrators and 9 translators are banned from school shelves throughout the United States, according to data collected by PEN America from July 1, 2021, to March 31.

Across all 50 states, Texas ranks first, banning 801 books across 22 districts, according to a PEN America report released Monday.

Beginning Sunday, Banned Books Week puts the freedom to read on the front page. The annual event, sponsored by a coalition of organizations including the American Library Association, GLAAD, National Coalition Against Censorship, PEN America and more, highlights the need for free and open access to information.

Common reasons for bans and challenges include “inappropriate” sexual content, “offensive language” and material “unsuited to any age group,” according to the American Library Association. However, these reasons target books critically discussing race, gender, class, sexual orientation and more, from “The Bluest Eye” by Toni Morrison to “All Boys Aren’t Blue” by George M. Johnson.

While this remains the reality for many scholastic bookshelves, radio-television-film freshman Akiya Blake said banning books limits students’ education. Coming from a high school with open access to educational materials and literature surrounding topics considered to be controversial such as reproductive justice, LGBTQ+ issues and racial injustice, Blake said all students should have the right to freely read.

“If people are interested in something and they want to know more about it, they shouldn’t come across (content and literature) that’s banned,” Blake said. “That hinders them and what they want to learn.”

Sharon Obinna, a speech, language and hearing sciences freshman, said banning books and teaching materials inhibits growth for students in the classroom, especially books like “Things Fall Apart” by Chinua Achebe, which tackles topics like racism and colonization.

“If you ban, for example, ‘Things Fall Apart,’ that’s a whole part of a culture that you are not allowing people to learn about,” Obinna said.

While not currently on the banned list collected by PEN America from July 1, 2021 to June 30, “Things Fall Apart” faced challenges in Texas in the past for its critical portrayal of colonialism, according to the National Coalition Against Censorship.

Mechanical engineering senior Deborah Lin said censorship can cause a slippery slope in regard to who holds the power to decide what is and is not allowed.

“How do we regulate something that’s so subjective to everyone?” Lin said. “Who is the right person to decide what should be censored? We should be really careful when it comes to censorship. If we censor (something), then we just believe that we’re in our own space, and everything is going the way we want to. I don’t know if the government should be too involved in something like this.”

Obinna said she believes censorship in public education limits more than it helps, leading her to hope for a future where lawmakers care to tackle issues often ignored.

“My hope for the future is that lawmakers grow more open to hearing these stories,” Obinna said. “For education in general, women’s health (is) not something that’s explained very well in schools, and it messes up a lot of young girls. Lawmakers should be more open to (topics like that) because it helps people grow.”