‘It’s just not enough’: Nearly 25 years later, UT’s auto admit rule struggles to diversify

November 29, 2022

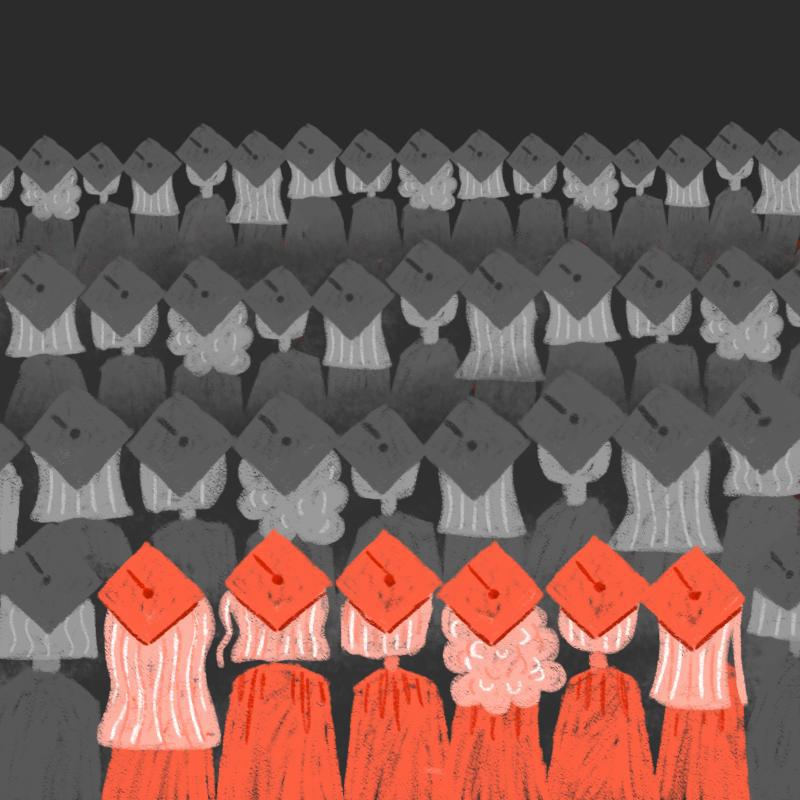

When state lawmakers implemented UT’s automatic admission policy nearly 25 years ago, it was intended to promote diversity on campus.

While the policy has slightly helped the University become more diverse, UT’s student body still doesn’t fully reflect the state’s demographics. Experts said the policy can only really be successful for marginalized communities if substantial financial aid is included.

“It’s just not enough,” said Stella Flores, associate professor of higher education and public policy. “It doesn’t have the success rate of diversifying the University or diversifying, maybe even by income, or even geography that I think the original creators of it intended.”

UT automatically admits the top 6% of graduates from every high school in Texas, making up about 75% of first-year in-state students, according to the University.

Automatic admissions began following the 1996 case Hopwood v. Texas, which set the precedent that Texas, Louisiana and Mississippi public universities cannot admit students based on their race in response to UT School of Law considering race as part of its admissions process. A year later, Texas lawmakers passed a bill to guarantee automatic admission to UT for students who graduated high school in the top 10% of their class.

Miguel Wasielewski, executive director of admissions at UT, said the state’s auto admit rule was created to recover the loss of diversity after Hopwood v. Texas, which he said caused the Black and Latinx student population to drop substantially. He said state legislators began the auto admission rule to ensure every high school in Texas had the opportunity for at least one of its students to attend UT and to promote diversity.

Wasielewski said legislators saw an equity issue as low-income students were more likely to attend “lower-tiered” schools and wanted to provide students with an opportunity to attend a top-tier university like UT.

“Because schools are different in their neighborhood representation and the resources that are available there,” Wasielewski said, “a lot of the schools that might have socio-economic challenges, they may have high representation of diverse students.”

Although UT’s racial and ethnic makeup has grown more diverse in the 25 years since the auto admit rule was implemented, the University’s student body is still largely white and comes from an upper class socio-economic background.

This problem is largely compounded by students of color being less likely to complete college than white students in Texas, Flores said, which stems from racial segregation still present in high schools, economic disadvantages in marginalized communities and a lack of academic preparation to enroll in college.

“It’s this cauldron of disadvantage that has basically built up over time,” Flores said. “When students don’t have access to schools or resources that middle-to-upper-income white students do, they have less opportunity to succeed in terms of higher education.”

While marginalized communities already face numerous obstacles to attend UT, Jeremy Fiel, associate professor of sociology at Rice University, who researches education, segregation and inequality, found the auto admissions rule is undermined by students with more means. He said high schoolers would switch schools their junior year to ensure their spot in the top 6% of the graduating class and a spot at UT — specifically white students switching to predominantly Black schools.

“The evidence specifically indicated that overall, white students are less likely to enroll in schools that previously have had higher shares of Black students,” Fiel said. “But after the policy, they were less averse to enrolling in schools with higher Black populations.”

For low-income students, Flores said the auto admit policy may seem unfair because although they get admitted to UT, they may not be able to afford it.

She said the automatic admissions rule can be successful if there was more financial support for those students. In 2018, the University implemented the Texas Advance Commitment, a program that covers the tuition for any Texas resident with a family adjusted gross income of up to $65,000. However, Flores said the program is too new to evaluate its effectiveness.

Out of all the first-year automatically admitted students who enrolled in 2021, 26% were coming from households with incomes below $60,000, according to UT. In comparison, 31% of automatically admitted first-year students in 2015 came from a household with an income below $60,000.

Flores said while scholarships assist low-income students, the decision to go to college is still difficult because some students are giving up the role they had in supporting their families.

“When you’re low-income, it’s not just about the tuition,” Flores said. “It’s about the role you fill to keep your family afloat. And that’s a really hard decision for low-income students. Do I leave my family for this opportunity?”

Jane Lincove, an associate professor of public policy at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, did research on Texas’ automatic admissions policies and said she found that where the student grows up, their race and income hold a big role in what college the student chooses to attend.

While the policy allows UT to diversify its incoming classes, Lincove said the holistic non-automatic admissions review overwhelmingly lacks racial diversity.

“If you want to start becoming more diverse, the University needs to actively do something,” Lincove said. “You can’t just say, … ‘You should come here because you have good academics.’”

Wasielewski said UT’s hope is to put less financial burden on the student’s family by providing resources, such as the Texas Advance Commitment, to make attending UT more affordable for students.

“A family that may not have any resources to be able to send their student to school, if they can’t find some way to cover those costs, then that student may never have the opportunity to pursue higher education,” Wasielewski said.

Flores said overall, the auto admissions rule worked to help make the University more diverse, as before it was implemented, University officials largely recruited from only upper-middle class high schools. While Flores believes more needs to be done to diversify UT, she said this rule at least sets the bare minimum that students from all high schools in the state have an opportunity to attend UT.

“In most games, somebody wins and somebody loses,” Flores said. “But I think the game is more equal now, because it wasn’t before.”