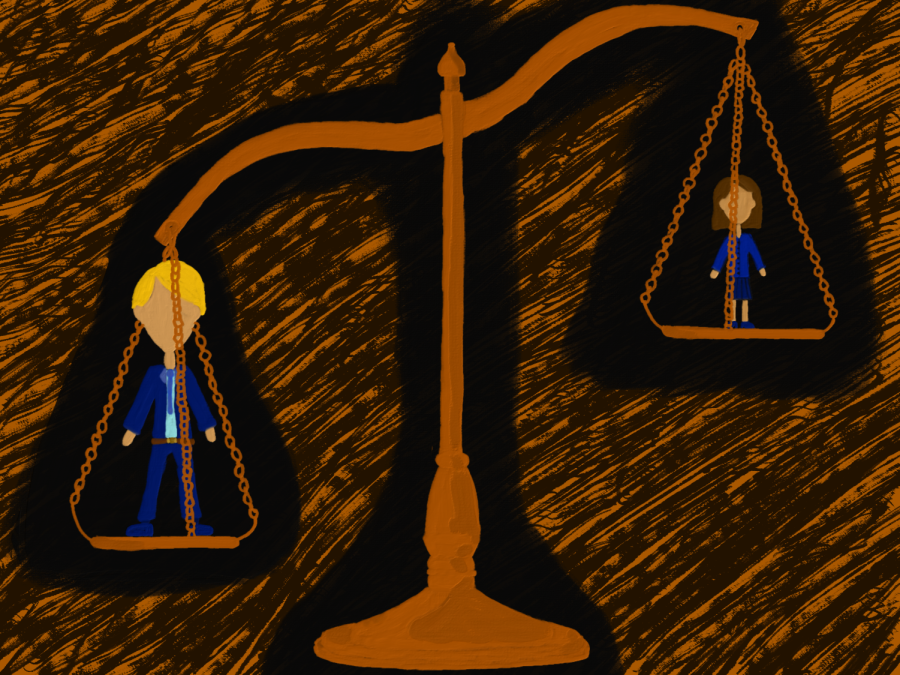

We must address sexism in law school

March 6, 2023

While we often acknowledge the structural discrimination women attorneys face, we fail to fully consider how sexist law school experiences directly impact women in politics and law.

As the Tulsa Law Review reports, “Study after study confirms female law students’ feelings of alienation, disillusion and discontent with law school and concludes that legal education is failing women.”

While schools like Texas Law try to shield women in law school from sexism, there is significant room left for necessary progress.

“Mutual respect, fairness and the equality of all students are core values of our community,” Texas Law Dean Bobby Chesney said in an emailed statement on Feb. 15. “Let us treat one another with grace and dignity, always.”

Regardless of Chesney’s statement, it is clear that women still experience a larger trend of sexism in law school.

A 2022 American Bar Association study reported that women, on average, constitute 37% of practicing attorneys — more than 10% less than the proportion of the population they comprise. While women made up a majority of law school students in 2021, constituting 51% of the current Texas Law student body, gender diversity does not protect them from sexism.

“Constantly, at law school, I am reminded that I am not supposed to be (at UT),” 2L student Julia Draper wrote in a statement. “Even though over half of UT law students are women, there are still professors who refuse to take our comments and questions seriously, male students who gladly take credit for our work and extracurriculars where women are always judged more harshly based on an unknown, impossible-to-meet rubric.”

The sexism that women in law school experience continues beyond law school. A 2021 American Bar Association study found that “women lawyers aren’t nearly as satisfied with their career experiences at law firms as men are.”

The results also showed that 82% of women lawyers have been mistaken for a lower-level employee and that 48% of women lawyers felt they had missed out on a case or assignment based solely on their gender. Additionally, women of color remain one of the most marginalized groups in law.

In a 2020 paper, associate professor Maryam Ahranjani of the University of New Mexico School of Law reported that the stigma surrounding women lawyers remains unchanged.

“Women criminal lawyers must mimic masculine norms to be successful in the field,” Ahranjani wrote.

Becoming a lawyer is already difficult. Having to overcome hurdles in an educational environment makes the process even more daunting.

For 2L student Zoe Dobkin, her law school experiences have illuminated the faults of those in the legal profession. She says this realization directly contradicts the moral and objective rigor we assume of legal professionals.

“It’s not like coming to law school is revolutionary, but (it) certainly (brings) a greater appreciation for the fact that lawyers and judges are humans with all their faults and biases,” Dobkin said. “Any argument or judgment is made by humans with preconceived notions, and the legal field is not immune to any of the societal biases, like sexism.”

Many legal professionals also go on to pursue political careers, and the U.S. government is riddled with the effects of this sexism. While the current proportion of women representatives is at its highest yet, that number only accounts for 25% of U.S. Senate representatives.

To address the sexism at UT Law and law schools across the country, we must change the culture surrounding professional women.

“It’s important for men, including myself, to not only use this moment to recognize the inappropriateness of this behavior, but also to reflect and make sure our own behavior comports with respect for women and to ensure that we are not complicit in other men’s disrespect of women,” 3L student Zachary Kolodny wrote in a statement.

Discussing this culture is a good starting point, but there are also other substantive measures we can take. For example, more intensive Title IX training is an effective way to empower law students to know their rights.

“I think there’s definitely a better way to teach criminal law; these are really tough concepts,” Dobkin said. “You can teach the doctrine and legal thinking and still call out the court rulings for being problematic and imagine newer and better ways to emphasize certain points more than others so that everyone in the classroom is on the same page.”

We must create space to discuss these issues because they bleed out into the real world. Law students are adults, and they soon will be professionals. It is unacceptable for us to maintain a workforce that discredits and overlooks women.

Muthukrishnan is a government and race, indigeneity and migration freshman from Los Gatos, California.