UT research explores why asthmatic children of color are more likely to go to ER

March 22, 2023

New UT research revealed that upper respiratory viruses might be why Black and Hispanic children are more likely to go to the emergency room for complications with asthma than white children.

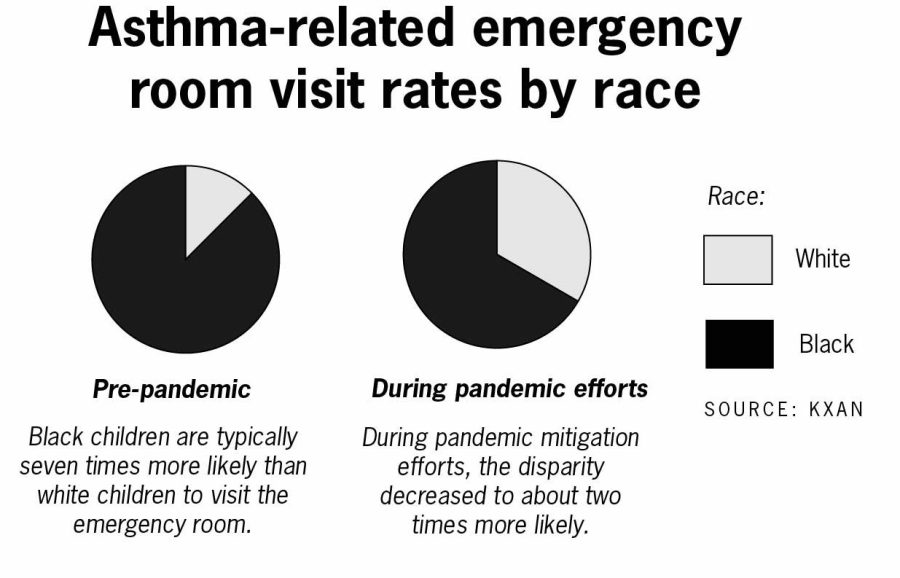

Results from the study published in November showed that Black children were almost seven times more likely to visit the ER for asthma-related issues than white children. However, because of the COVID-19 prevention measures like mask usage and social distancing, the disparity decreased to around twice as likely, indicating that children of color may be more susceptible to respiratory viruses.

“(This research) is pretty novel,” said Darlene Bhavnani, lead researcher of the study and assistant professor of population health. “I don’t think anyone, as far as I can tell, has asked the question about whether these disparities and asthma exacerbations are driven in part by viruses, so it’s pretty exciting to think about.”

The study compared emergency room rates for asthma-related complications in Black, white and Hispanic children in Travis County from before, during and after the pandemic where mitigation efforts took place.

While the research does not address the underlying causes behind this disparity, Bhavnani said she believes there are environmental factors that could be observed, like crowding in households due to lack of space and poor ventilation.

“We, as a field, have recognized these disparities for 40 years or more now, and we haven’t made a dent in them,” said Elizabeth Matsui, professor of population health and pediatrics and co-author of the study. “I argue that we haven’t made a dent because we’ve been looking at the problem through a purely biomedical lens. The importance of this kind of work is that we’re finally looking at potential root causes.”

Matsui said medical officials noticed a reduction in upper respiratory viruses, like the common cold. Researchers also observed that all asthma-related emergency room visits decreased.

Additionally, children of color may have higher exposure to respiratory diseases due to higher outdoor air pollution, Matsui said. Some families also have more frontline workers in their household, increasing their vulnerability from a family member bringing a virus back into their home.

“This is incredibly helpful because if doctors start to understand things like housing needs of patients, there are resources for patients and families to address housing-related exposures that are unhealthy,” Matsui said. “Doctors are incredibly busy, but it’s not that hard to put in some referral or providing information to families for medical-legal support or housing advocacy support outside of the clinic setting.”

As the purpose of the paper was to generate this hypothesis about asthma complication and respiratory viruses by observing trends, Bhavnani said that more work needs to be done before a final conclusion can be drawn.

“We’re not at a point with this particular question where we’ve built enough evidence to influence policy, but the goal is to get there,” Bhavnani said. “The goal is to be able to understand these exposures and design realistic interventions based on our research. … We need well-designed studies to continue this work and generate more evidence.”