Groundwater drilling alters Earth’s tilt, new study finds

June 26, 2023

A study published on June 15 involving UT researchers found that groundwater depletion contributes to rising sea levels, which is estimated to cause a drift of Earth’s rotational pole.

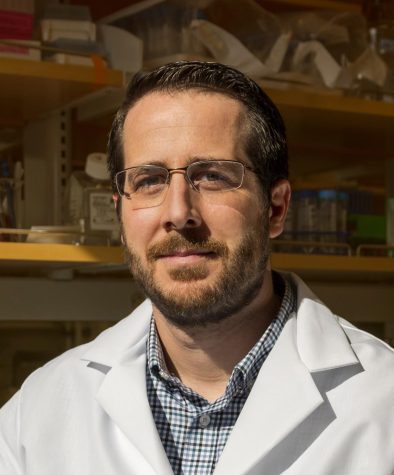

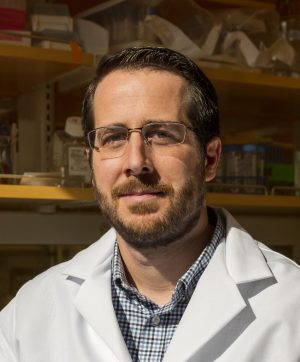

“If you take the water out of the ground, eventually it ends up in the oceans, and that would cause sea level to rise,” said study author Clark Wilson.

Researchers observed the phenomenon of polar drift — the migration of Earth’s rotational axis — to determine the extent drilling for groundwater causes the ocean to rise. Lead author Ki-Weon Seo said his team found that a disturbance in the position of the Earth’s axis correlated with a rise in sea level due to groundwater returning to the ocean.

“Any mass change on Earth is a source of polar drift,” Seo, a professor at Seoul National University in Earth Science Education, said in an email. “Water and ice mass changes on land eventually affect ocean mass … ice mass loss from Antarctica is directly linked to sea level rise.”

Polar motion has been observed since the early 1900s, and the study took into account data ranging from 1993 to 2010. The rotational axis traveled around 40 feet from its original position, said Wilson, professor emeritus in the Department of Geological Sciences. In addition to polar drift, the axis also experiences a “wobble” due to changes in mass affecting the symmetry of the Earth.

“It’s more or less like the wobble you see in a frisbee,” Wilson said. “If you’re a terrible frisbee thrower, it leaves your hand and it wobbles through the air. The reason it wobbles is because the rotation axis of the frisbee is not perfectly aligned with the axis of symmetry of the frisbee. … That’s what’s going on with the Earth.”

Knowing the position of the rotational axis is critical due to the role it plays in GPS technology, Wilson said.

“Because the reference frames for your GPS are the satellites that are orbiting the Earth, you need to translate your position relative to those satellites to a geographical location on the Earth, and that requires you know exactly where the rotation axis is,” Wilson said.

If groundwater depletion continues at its current rate, polar drift would continue at a rate of 4.3 centimeters per year, Seo said.

Eventually, polar drift due to this cause will diminish as groundwater supplies run dry due to continual drilling, Wilson said.

“At some point, assuming this continues, if there’s not a big recharge event like huge amounts of rainfall, then it’s going to deplete some or many of these aquifers,” Wilson said.

Further research is needed to determine the significance of polar drift data gathered before 1993, Seo said. He said since data has been collected for over 100 years, it may hold some answers to help form a more complete picture of the causes of polar drift.

“Ice loss associated with warming climate would not be the only cause of ocean mass increase,” Seo said. “We need to consider groundwater seriously for sea level rise.”