My high school English classrooms were not ones that celebrated diverse perspectives. The school district regularly challenged and banned books from classroom libraries. So, when I took my first English course at UT — one based around controversial works — I anticipated reading a wide array of diverse literature that I’d previously been unable to study in a classroom setting.

Instead, I was assigned a reading list consisting only of 19th and 20th century works written by white Irish and British authors. These novels, while widely considered essential to Western literary canon, did not reflect the variety of works that now define the literary world. A strict adherence to traditionally canonical works does not benefit students.

The literary canon is the set of books and authors that are deemed to have the highest cultural significance. Since its emergence hundreds of years ago through today, the concept of the canon has sparked a widespread debate over its value and contemporary relevance.

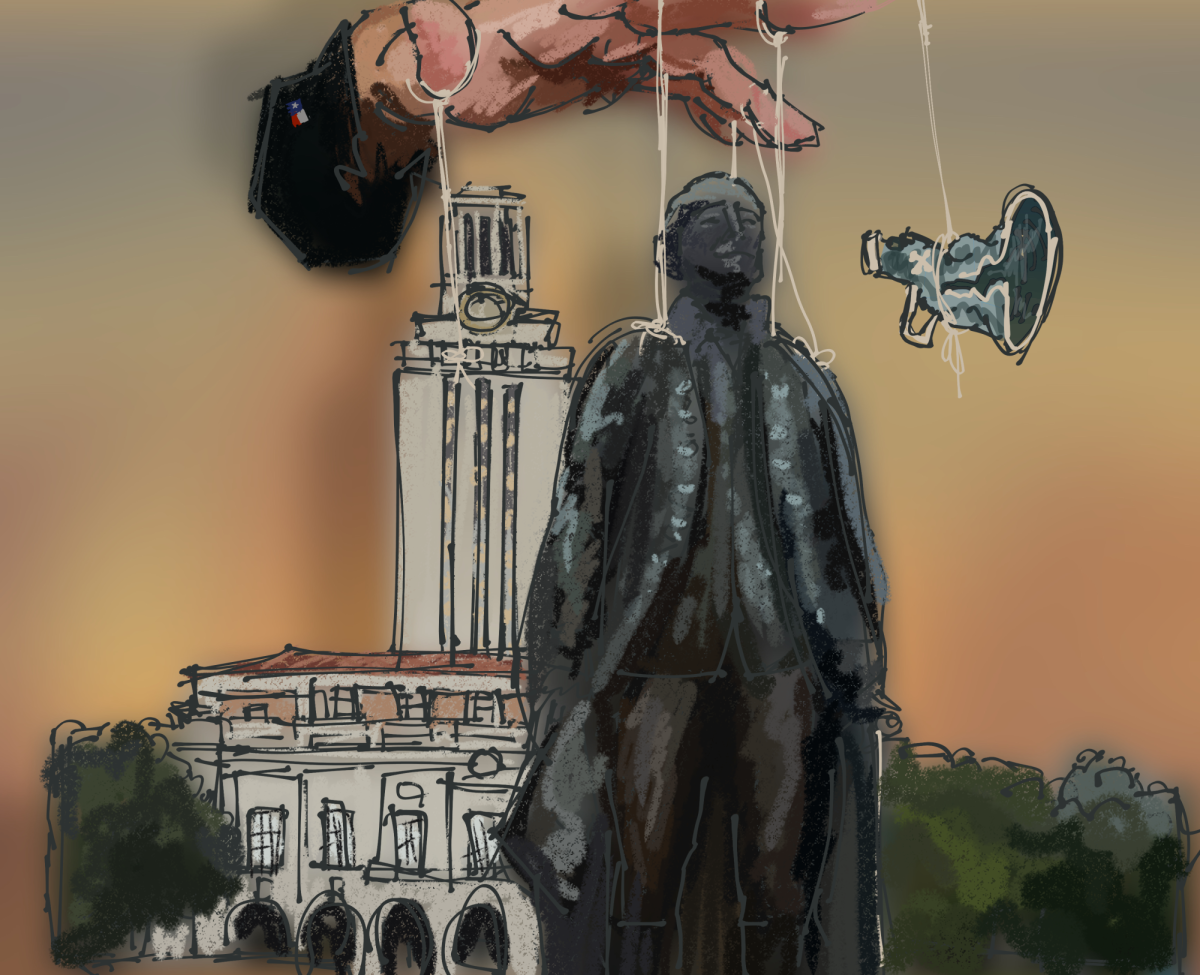

With the rampant statewide book bans and bans on diversity, equity and inclusion offices on college campuses, this discussion is more important for the English department to have than ever. English professors must continue to highlight diverse literary works and welcome students’ fresh takes on canonical writings.

“There is no accurate and proper or appropriate discussion of canonical writings without the discussion of diversity,” English professor Helena Woodard said. “If the diversity aspect is left out, then there is not full accuracy in looking at works.”

Woodard, who teaches courses on critical race theory and American literature, said exclusions were inherent in the development of the canon, leaving the public with mostly writings by white male authors. To combat this in her courses, Woodard utilizes retellings of famous novels written by people of color alongside the original texts to provide students greater cultural context.

“It’s a bad idea to continue to use exclusionary practices, to keep our students from knowing the accuracy of past relationships that have been fraught with respect to women, people of color and the LGBTQ+ community,” Woodard said. “So learning then what happened in the past helps us to avoid or at least to be more reparative going forward.”

Teaching a broad range of texts also helps students find works they connect with, whether it affirms their identities or challenges their beliefs. English professor Lydia CdeBaca-Cruz said the English department is working to meet the demand for courses that engage with race, ethnicity, gender and socioeconomic class.

“The value that I think providing diverse voices offers is to really broaden what is thinkable, what is imaginable, which opens up the scope of problem solving and a whole array of creativity,” CdeBaca-Cruz said. “What I’m really out for is that transformative learning experience. That usually comes from exposing students to new voices, different voices, and different experiences, or maybe the same voices but through a different lens.”

Though incorporating lesser-known works is important, the literary canon does still have a purpose in the University’s English courses. When introducing students to literature, a predetermined set of essential works can help students develop a shared set of references and cultural understandings. Incorporating noncanonical works does not dilute the value of these core texts. Students will leave UT with a broader range of knowledge and deeper cultural awareness if the English department continues to emphasize diversity and reconsiders what it deems as essential works of the canon.

“I’m one who thinks the canon is very important, but should not be exclusionary,” Woodard said. “Books that have only recently been taught, that were left out of the canonical realm, also belong in that place.”

Henningsen is an advertising and English major from Austin, Texas.