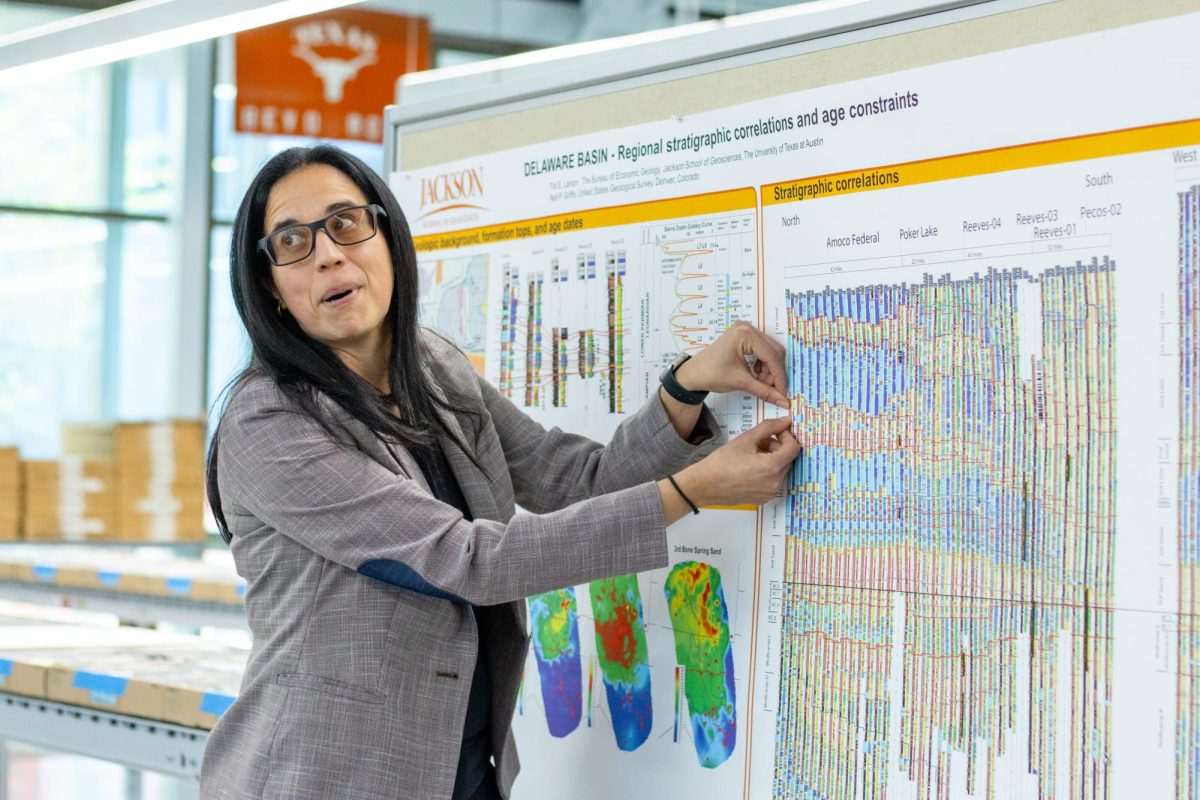

A UT research team received a $2.6 million grant to research air pollution’s nonuniform effect on Travis County children.

The grant, received from the National Institute of Health, focuses on the impact of zoning, poverty, race and pollution composition on the rates of pediatric asthma-related hospitalizations and emergency department visits. Since this study overlaps health, sociology and policy, the research team members are scattered throughout the University, from Dell Medical School to the School of Architecture.

“It’s a really neat, interdisciplinary team, thinking about the same issue though from so many different perspectives,” said Catherine Cubbin, associate dean for research at Steve Hicks School of Social Work.

A 2021 study co-authored by Cubbin found that eight times as many Black children and two times as many Latinx children as white children visited the emergency department or hospital for asthma in Travis County. However, poverty and income only partially accounted for this disparity, leading to questions the upcoming study aims to answer.

Cubbin said the location and toxicity of pollution sources may also play a role in pediatric asthma’s disproportionate impact in the county.

“Not all air pollution is created equal,” Cubbin said. “There’s certain components of air pollution we think are more harmful than others.”

The 2021 study found pollution and asthma rates varied drastically from neighborhood to neighborhood because pollution sources are concentrated in lower-income, more segregated communities, said Elizabeth Matsui, researcher and professor of Population Health and Pediatrics.

Most pollution research is done by zip code rather than individual neighborhoods, so finding such large disparities from one community to the next better informs possible solutions tailored for Travis County, Matsui said.

“When you’re thinking about whether air pollution matters for disparities, if you look at an entire county, you’re missing the picture,” Matsui said.

To examine why pollution sources are located in specific areas, researchers must understand zoning laws, said Elizabeth Mueller, investigator and professor in the School of Architecture. Zoning laws shield wealthier neighborhoods from pollution sources, but these laws are virtually nonexistent in unincorporated areas outside Austin city limits.

“We know about planning within cities, and now we’re going to learn about these processes outside cities and try to understand what the levers are for protecting people and for changing things in those situations,” Mueller said.

Once a major pollution source like a factory is present, it takes a good deal of effort to get it shut down, Mueller said. For example, enormous, dangerous gasoline tanks littered Central East Austin in the 1950s, and grassroots environmental groups fought for decades to get them removed in the early 1990s.

When pollution sources are clustered in lower-income segregated neighborhoods, Mueller said the only viable course of action is to prevent other hazards from being built and mitigate the effects of what’s already there.

Researchers hope this study’s findings encourage local policymakers to consider pollution “through an environmental justice and health equity lens,” Matsui said.

“I’m very excited about this project,” Mueller said. “It’s a great way to bring together information about how our segregated patterns of development show in health outcomes. It’s the kind of project universities should be doing.”