New work from UT researchers found that childhood neighborhood cohesion, the amount of trust and belonging a person feels in their community, impacts cognitive health later in life.

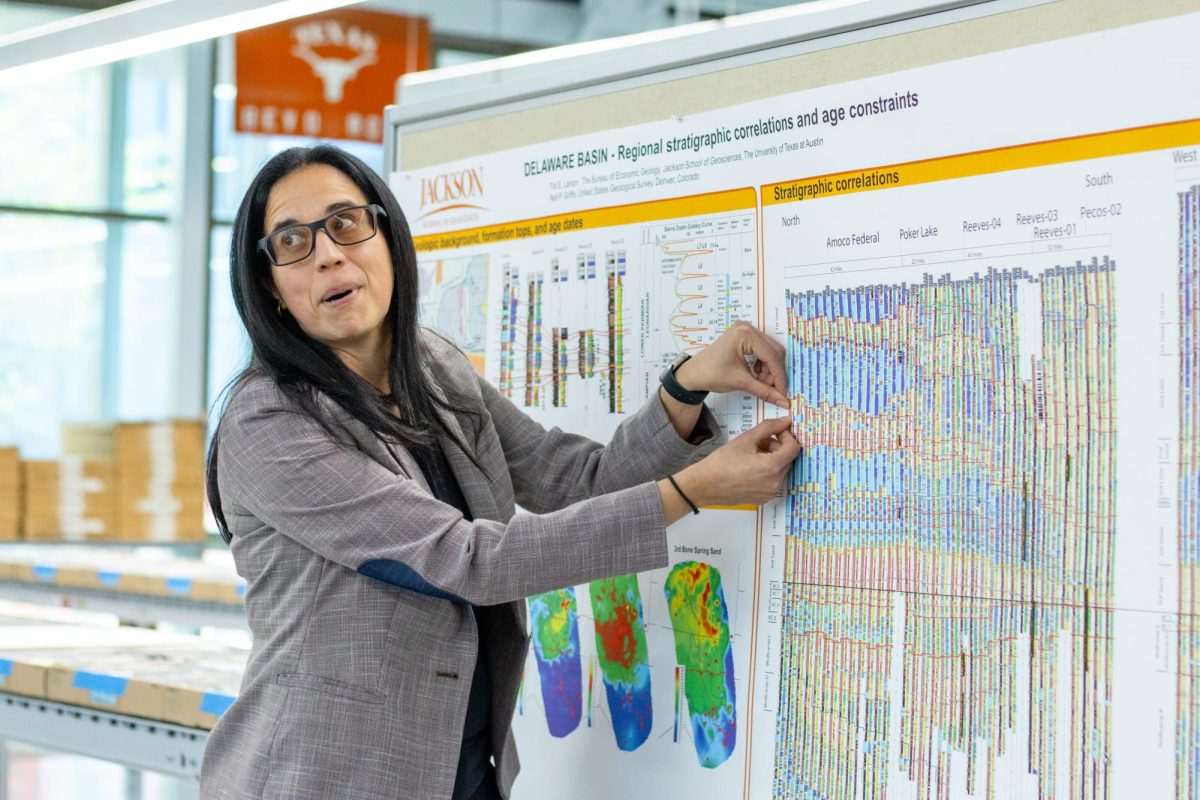

Graduate research assistant Jean Choi said she used the large, nationally representative Health and Retirement Study to compare data on both individuals’ cognitive functioning and recollections of their childhood neighborhoods to establish a link between the two. She found more positive neighborhood cohesion during childhood correlated with better cognitive health in late midlife and older adulthood.

“Neighborhood cohesion refers to the extent to which people feel that they belong in the place that they live, that they feel like they can trust their neighbors and that there’s somebody around to provide support to them in their neighborhood,” study co-author Elizabeth Muñoz said.

Choi said she focused on the factor of neighborhood environments because this important social determinant of cognitive health remains relatively understudied.

“I’m interested in cognitive health because the aging population in the United States is rapidly increasing and the number of cognitive disorders or Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias are increasing as well,” Choi said. “There’s still a lack of effective treatments available for any of these, so researchers have directed attention to identifying factors that can be modified to promote the cognitive aging process.”

Muñoz, a human development and family sciences assistant professor, said the research considered neighborhood cohesion during childhood in particular because previous research established how early life experiences critically influence health later in life.

“We have looked at early-life socioeconomic status, early-life health conditions, more individual-level predictors of later-life health,” Muñoz said. “(This research is) moving beyond the individual level, looking at the neighborhood environmental level and seeing how those factors also relate to cognition.”

Choi said she compared data on neighborhood cohesion with data from tests measuring various types of cognitive functioning in adults over 50, such as recall memory, working memory and processing speed. She said the findings emphasize the importance of childhood as an important developmental stage for early brain growth with long-lasting impacts that may not appear until late in life.

“Due to age-related changes, older adults may experience greater functional limitations or decreased social networks,” Choi said. “They may be more spatially confined in their environments compared to adults in their earlier stages of their life course.”

Muñoz said the researchers only established an association between neighborhood cohesion and cognitive health, leaving it up to future research to find the psychological, social and behavioral mechanisms behind this.

“Jean does bring up in her paper that living in more cohesive neighborhoods could promote more health behaviors,” Muñoz said. “It can make individuals more comfortable in their neighborhood and that promotes behaviors like exercise (or) social interaction — all things that we know relate to cognitive functioning later in life.”

Choi said the findings underscore the importance of looking at neighborhood environments when considering methods for improving the cognitive aging process.

“It shows that it’s important to look beyond just individual-level health and risk factors,” Choi said. “It emphasizes the importance of looking at neighborhood environments in childhood as well and intervening earlier in the life course when looking at cognitive health outcomes in later life.”