A new target found for treating the most common form of pediatric leukemia, according to UT research published Oct. 7.

T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, or T-ALL, is a cancer of T-cells that develop into malignant leukemia cells typically through genetic mutations before traveling to the rest of the body in a trait unique to leukemia, said senior author Lauren Ehrlich.

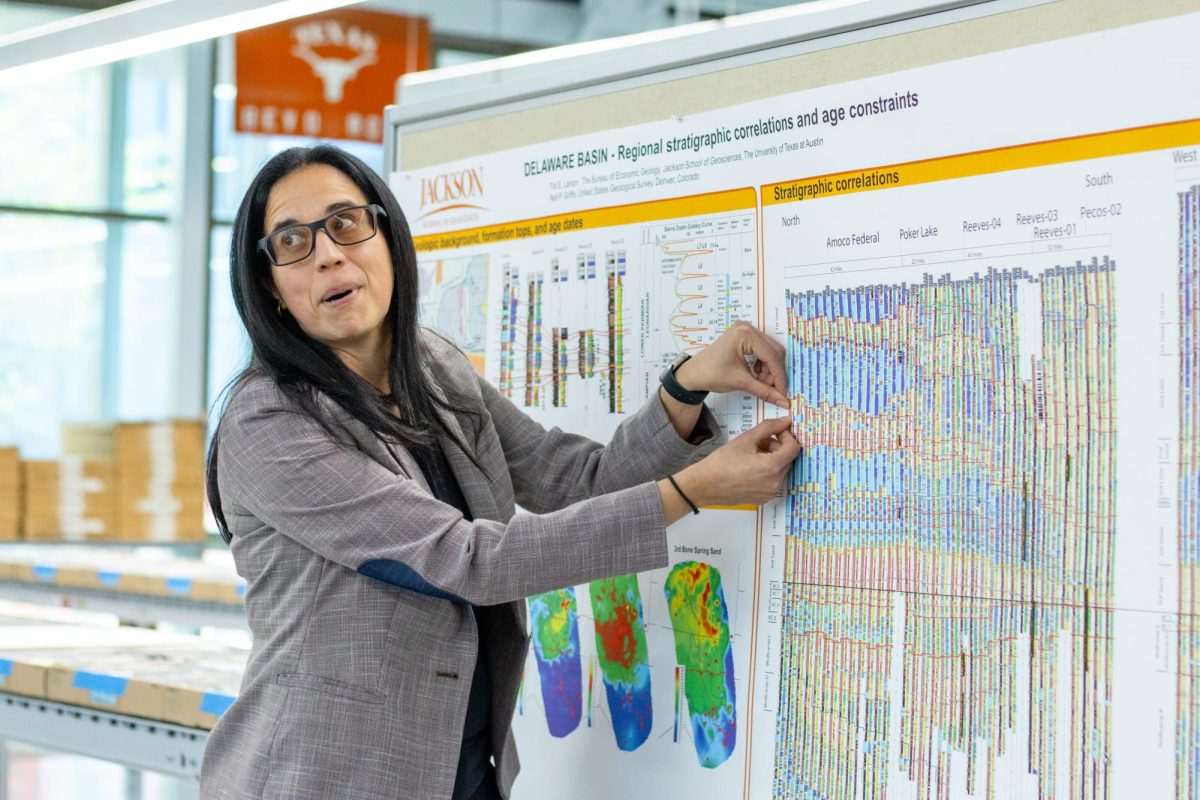

“My lab has been interested in trying to understand how the tumor microenvironment supports leukemia progression,” molecular biosciences professor Ehrlich said. “We’re really interested in how signals from sort of surrounding cells in the thymic microenvironment influence normal T-cell development.”

Interest in pursuing this research started after previous findings from the lab found that leukemic cells cannot survive on their own unless placed with other cells from the tumor microenvironment, or the environment specifically around a tumor, said co-first author, Ryan Humphrey.

“We were seeing this really interesting phenomenon where these cells were being co-opted to drive cancer survival,” Humphrey said. “Some of our initial in vitro results when we put these two cells together in culture found that leukemia cells alone, even though they’re cancer cells, won’t survive without these additional cells next to them.”

The researchers identified the cells aiding cancer survival as myeloid cells, typically associated with aiding immune responses, Ehrlich said.

“Earlier work had shown that they make some growth factors, in particular, the leukemic myeloid cells make some growth factors that the leukemia cells can use to survive and proliferate,” Ehrlich said. “We found that if you just took the leukemic cells and put them in culture, and you added those growth factors that the myeloid cells made and that we had previously found were important for myeloid mediated T-ALL survival, that wasn’t sufficient for them to survive.”

The researchers then identified integrins, a receptor on the surface of the cells responsible for mediating contact between myeloid and leukemic cells, Ehrlich said.

“What we did find is that these integrins were upregulated on our cancer cells relative to healthy T-cells or develop healthy developing T-cells specifically,” Humphrey said. “We found that yes, integrin signaling was critical for this interaction.”

In addition to the integrins, there are signaling proteins activated upon contact between myeloid and leukemic cells and responsible for continued interaction, Humphrey said.

“We were able to show that by either sort of going in reverse and blocking the integrins themselves or using some clinical inhibitors to this pathway, if you get rid of these proteins, the leukemia burden will go away, and the mice that we’re testing on would survive longer,” Humphrey said.

The current treatment for T-ALL is a multi-drug chemotherapy that patients will hopefully respond well to, and if not, there aren’t many alternative pathways of treatment, Humphrey said.

“You could start to think about how to turn this kind of basic research on how the tumor microenvironment is supporting and how we could start to move that towards something that would be clinically targetable,” Ehrlich said.