Dr. Elizabeth O’Brien has always displayed an interest in medical history. Whether reading medical textbooks for pleasure or hearing patient stories from her mother’s OBGYN hospital shifts, O’Brien gravitated toward the subject from a young age.

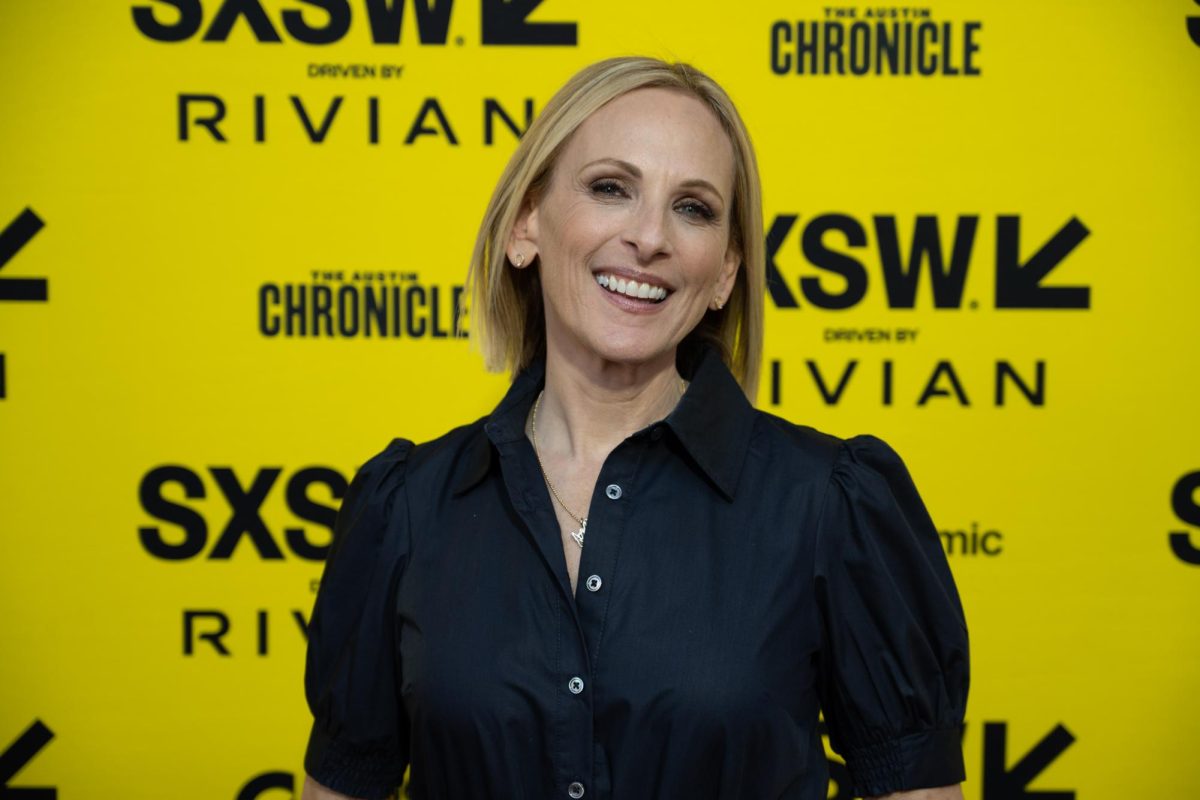

Years later, lawyers, judges and doctors similarly gravitated to O’Brien when she produced her own research on the history of reproductive injustice in Mexico not long before the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision and the overturning of Roe v. Wade. The 2019 Ph.D. recipient, now a tenure track professor at the University of California, Los Angeles, teaches the history of science and medicine and of Latin America and the Caribbean. O’Brien said this job came to her because of the research and dissertation on reproductive injustice, obstetric violence and obstetric racism in Mexico she obtained and produced while at UT as a doctoral student.

“After I graduated, people kept asking me to comment on the history and politics of abortion,” O’Brien said. “People are interested in that perspective from Mexico because Mexico has an intertwined relationship with U.S. history, even in terms of pregnancy and fertility control.”

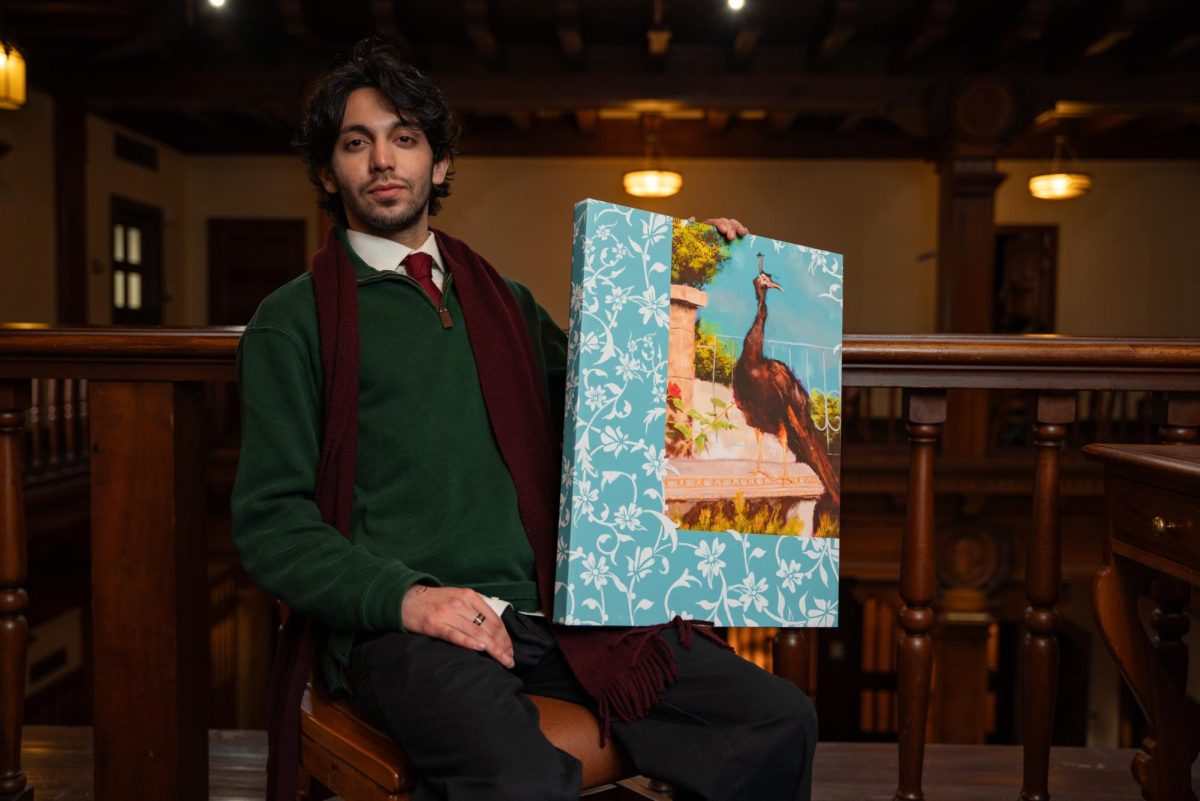

A book of her research, “Surgery and Salvation: The Roots of Reproductive Injustice in Mexico, 1770-1940,” will be published Nov. 14. However, with the attention her research received in the past few years, O’Brien already shared aspects of her research with those looking for historical perspective in a time when pregnancy termination proves increasingly controversial.

“In other states, when I’ve been talking to doctors, professionals and historians in conversation with lawmakers, people are very concerned about what’s going on in states like Texas,” O’Brien said. “They feel bad for the doctors, or they feel bad for the women there.”

She said in states such as Texas with newly altered abortion policies, reproductive healthcare professionals worry about the conflict between providing desirable healthcare for patients and laws preventing pregnancy termination when it may be essential. This led to a lack of healthcare providers wishing to practice in the state. Out of concern for this issue, professionals use O’Brien’s research for an understanding of what people historically think about reproductive procedures to gain perspective on how to move forward.

“My book questions things people would be quick to label as abortion today,” O’Brien said. “Doctors back then didn’t call them abortion. It’s not that common knowledge that women were very free to regulate their own fertility and pregnancies until the 1890s.”

To successfully break down this complicated history, O’Brien’s previous dissertation supervisor Matthew Butler said her study featured a tremendous range. The amount of 18th-century Mexican medical theses and accounts of sometimes gruesome operations O’Brien read made her research humane and detailed.

“She always found ways to foreground the experiences of Mexican women, which is a hard thing to do methodologically to recover those voices,” said Butler, an associate professor of history.

Another UT history professor on her dissertation committee, Seth Garfield, said the extensive work O’Brien produced represents the noteworthy work students can produce with dedication. He also said her work could inspire researchers to think about different questions, sources and approaches to make history more inclusive.

Although not an easy feat to achieve, O’Brien’s work proves worthwhile as it aids doctors and policymakers in making more informed decisions while exposing readers to a better understanding of society.

“I’m uncomfortable every day I write about devastating pregnancy outcomes,” O’Brien said. “Pregnancy is still dangerous, and it’s an uncomfortable thing to write about. So, we have to sit with that discomfort.”