UT researchers developed a water filtration device using Navajo pottery to provide clean drinking water for members of the Navajo Nation.

The researchers published this technique in a paper on Oct. 23. A large amount of uranium was mined from the Navajo Nation’s minerally-rich land in the Southwest during the 20th century, polluting the area and groundwater, lead researcher Lewis Stetson Rowles said. Rowles said about 30% of Navajo houses are not connected to a public water supply, so many houses store water for long periods of time, causing microbial contamination.

“Lack of close access to a safe water source has led to people needing to either travel far away to collect water they know to be safe and then store it at the house or have water delivered,” said Rowles, civil engineering and construction assistant professor at Georgia Southern University. “That’s the gap we’re aiming to address with these filters that can disinfect water at the household level.”

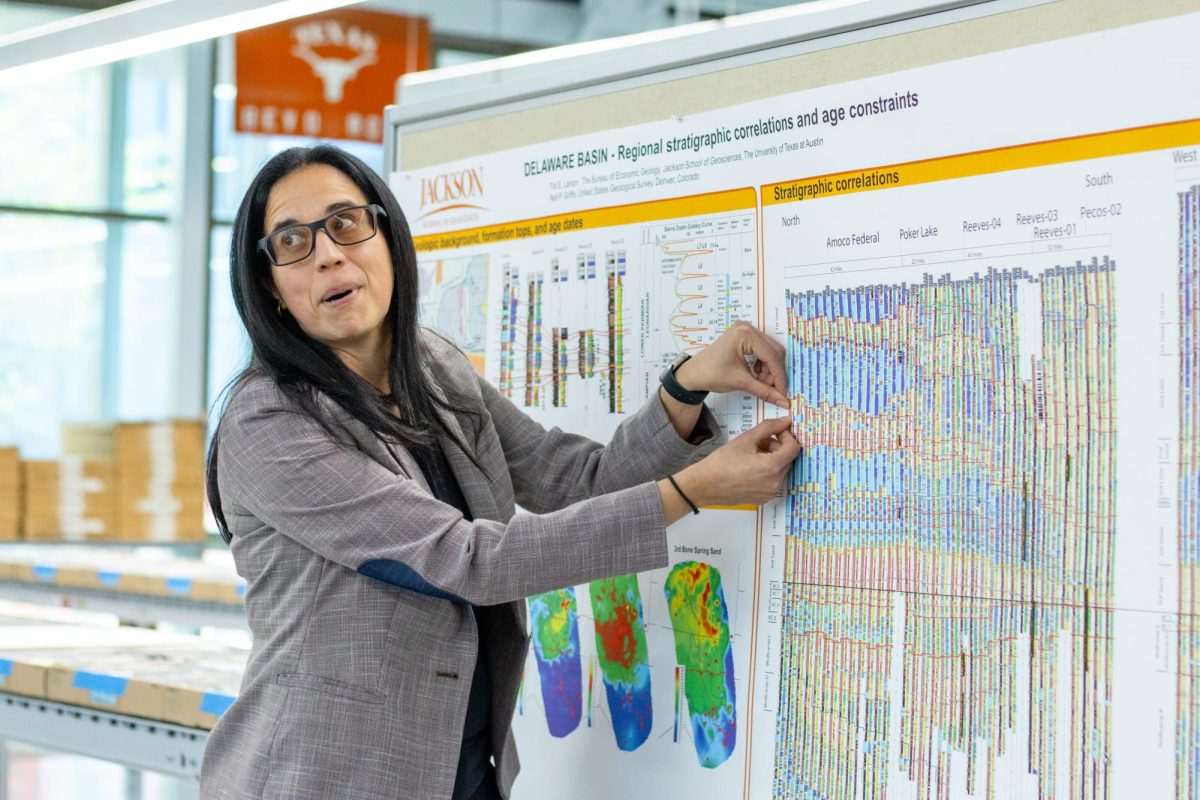

The project originated in a University of South Carolina undergraduate nanotechnology class Rowles took, taught by research co-author Navid Saleh. The class took a trip to Navajo Nation to learn about their water crisis, motivating Rowles to pursue research centered around Navajo Nation through a graduate degree at the UT, where Saleh is now a civil, architectural and environmental engineering professor.

“This work exemplifies some of the things that Dr. Saleh and I try to involve in research, (which) is trying to integrate local knowledge into scientific discovery,” Rowles said. “People are the end users so they should be included or kept at the center of technology development and its process.”

During trips to Navajo Nation, Rowles and Saleh connected with Deanna Tso, a Navajo potter and co-author of the research, who worked with them on creating water filtration using ceramics and showed them how to make Navajo pottery.

The researchers combined local pine tree resin with the Navajos’ centuries-old pottery technique, lining clay pots with the resin and incorporating silver nanoparticles found in the resin to kill bacteria in water and make it drinkable.

“The Navajos, rightfully so, have a large mistrust for outside influence, rooted from that neglect and environmental injustice that happened during that period (of mining),” Rowles said. “We wanted to use materials like ceramic, since pottery is central to the Navajo ethos, and the pinyon resin (that) has a long history of being used there, to potentially try and bridge some of that distrust.”

Rowles said the researchers’ approach addresses some problems with past ceramic water filters, such as the nanoparticles being embedded in a coating that keeps them from uncontrollably dissolving. Since the nanoparticles kill the bacteria, the device must keep them on the filter while still allowing them to dissolve at a controlled rate, which the pine tree resin can do.

The team plans to further collaborate with the Navajo community to introduce the filter for use. Saleh said the project serves as an example of technology development placing people at the center and demonstrating the power of Indigenous knowledge.

“We should never consider Indigenous people, their knowledge, as a complement (or) as an afterthought,” Saleh said. “My technology, our effort that we have made, it can make life a little bit better, but even without it they have lived and they will live. They don’t need us. We need them.”