Austin residents worry that the planned expansion of Interstate 35 could repeat the road’s role in the historical segregation of the city.

In 1928, Austin forced Black residents to the east side of the city and used East Avenue as a symbolic depiction of the city’s racial divide, according to Pease Park Conservancy. In 1962, the construction of Interstate 35 along that road created a physical barrier, according to the Reconnect Austin campaign.

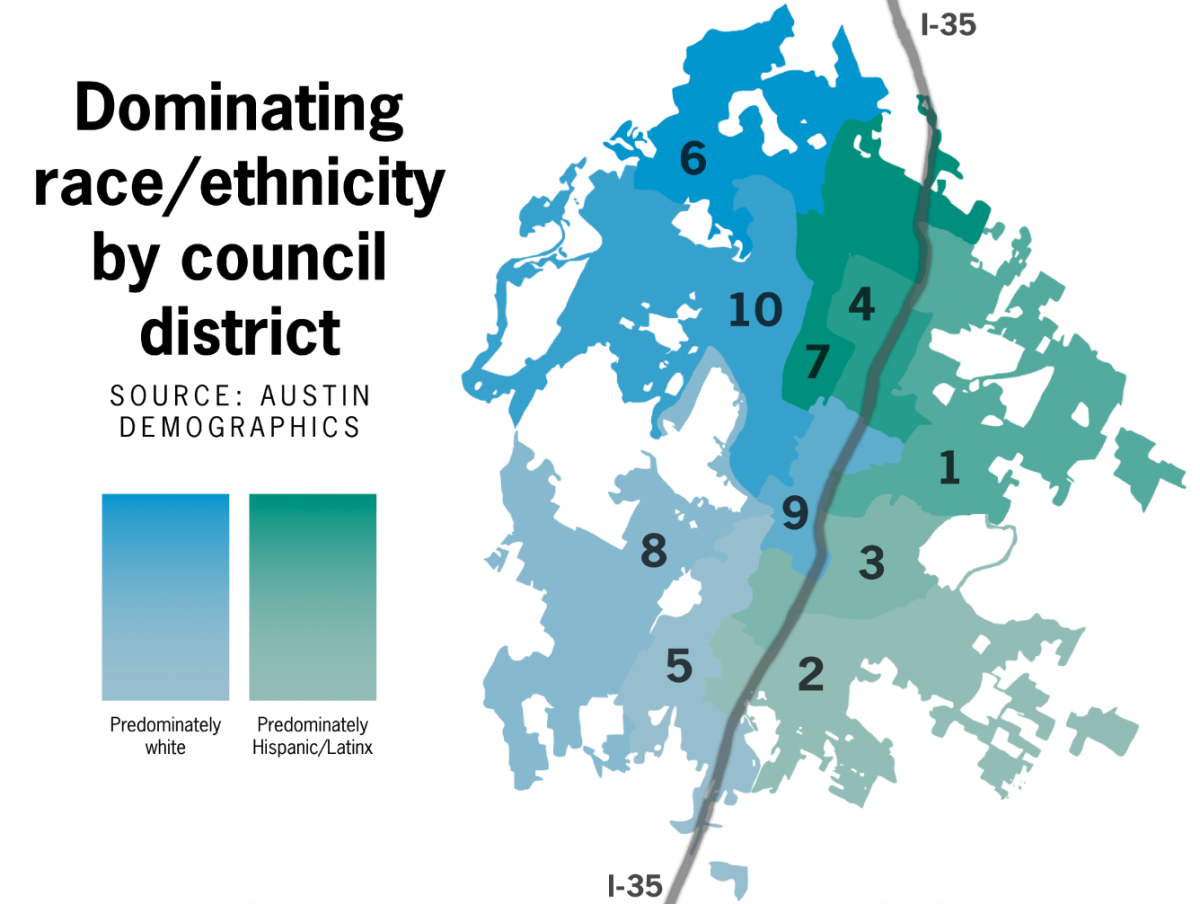

In the three districts east of the highway, Hispanic residents make up 19% more of the population than in the seven districts in the west. Black residents make up 6% more respectively, according to Austin Demographics. This raises questions regarding the displacement and quality of education of Black and Hispanic residents, along with a possible diminishment of their sense of belonging, said Dr. Ricardo Lowe, a postdoctoral fellow in race and public policy.

“You can only take so much at some point,” Dr. Lowe said. “It’s really annoying to think about these types of things happening so often and continuously in the city of Austin.”

In a community impact study for the expansion, the Texas Department of Transportation analyzed 30 neighborhoods in Austin. Seven of them had a population of at least 60% minority residents, and all seven fell on the east side, except UT. Of those seven, six fell under the list of poor walkability and bikeability — all but one on the east side.

TxDOT analyzed three different models of the I-35 expansion and chose the model with the least negative environmental justice impact which set 59 businesses for displacement, eight of which serve minority communities and 19 of which lie below the poverty level.

According to TxDOT, these displacements could cost several hundreds of jobs. Lowe said regardless of whether an individual sits in the displacement “line of fire,” they can feel discouraged witnessing close community members in line for displacement.

Austin Democrats president Craig Nazor said he has lived in Austin since 1987 and has noticed the role of the highway in the city’s division. He said building a bigger wall would only make it worse.

“We still have quite a way to go,” Nazor said. “The segregation has driven a lot of poor people out of Austin of every kind, usually people of color because they tend to have less money because of our past racism. It’s still an issue. It’s an old wound.”

Jonathan Newby, a second-year American Studies graduate student, said he knew of Austin’s racial division before moving here, but noticed it more as he drove through the city.

“Highways are, by their nature, dividing communities,” Newby said. “It’s hard to walk across the highway. It’s hard to even drive across the highway.”

He said the city should focus on constructing community development and schools on the east side, referencing the University’s possible expansion to the east which plans to add entertainment or athletic facilities.

Dr. Lowe said the quality of schools continuously pushes Black residents out of Austin.

“When it comes to certain things, they’re gonna put it in certain neighborhoods and certain people are going to be affected,” Dr. Lowe said. “People don’t want to call it racism — well, they need to figure out what exactly it is because that’s what it comes off as.”