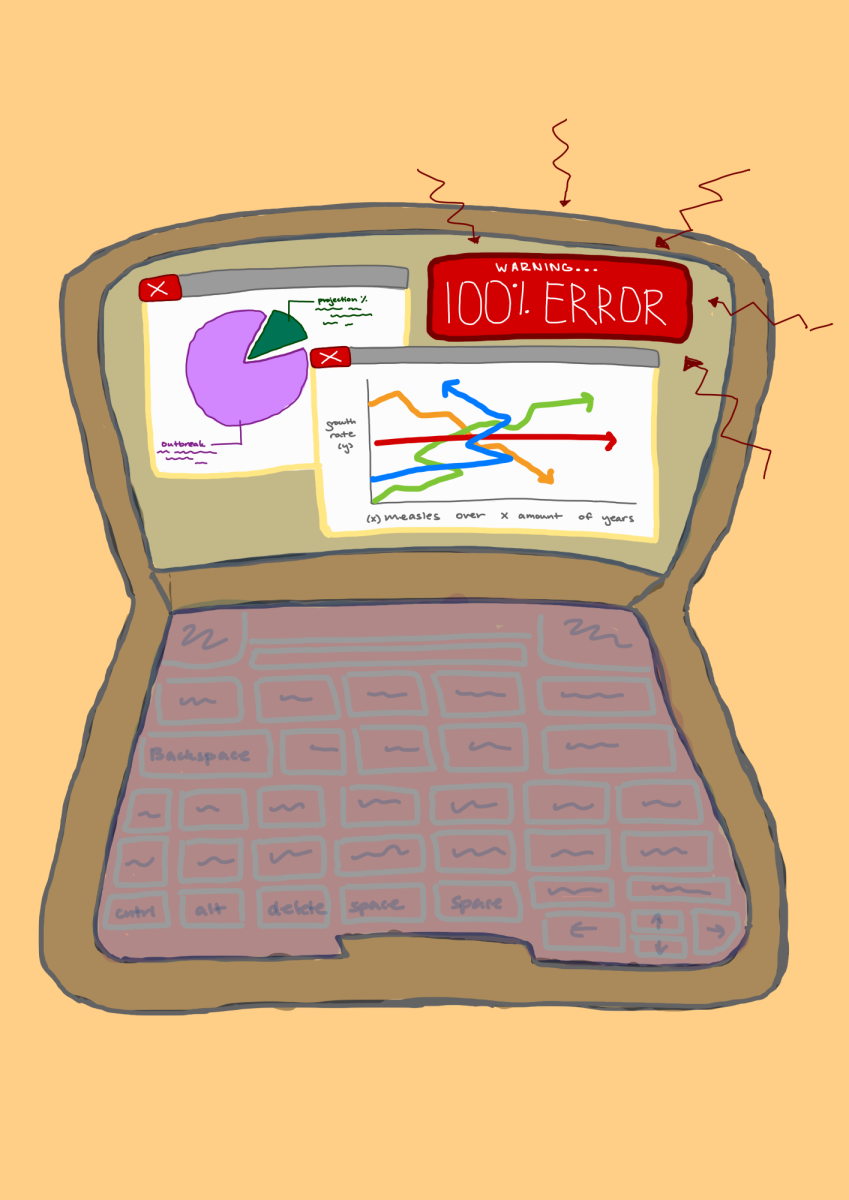

As humanity grappled with the unprecedented challenges of COVID-19, the foothill yellow-legged frog faced a pandemic of its own, one that endangered the species.

Since the 1990s, Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, or Bd, infections have spread through the population. UT postdoctoral fellow Anat Belasen led a team of researchers that deemed climate change and habitat loss driving forces behind the “frog pandemic,” according to a study published on Jan. 31.

Bd is a fungal pathogen that has infected frogs across North America’s West Coast. Belasen united a team of dedicated frog and disease researchers to study what factors may impact the spread of disease, she said.

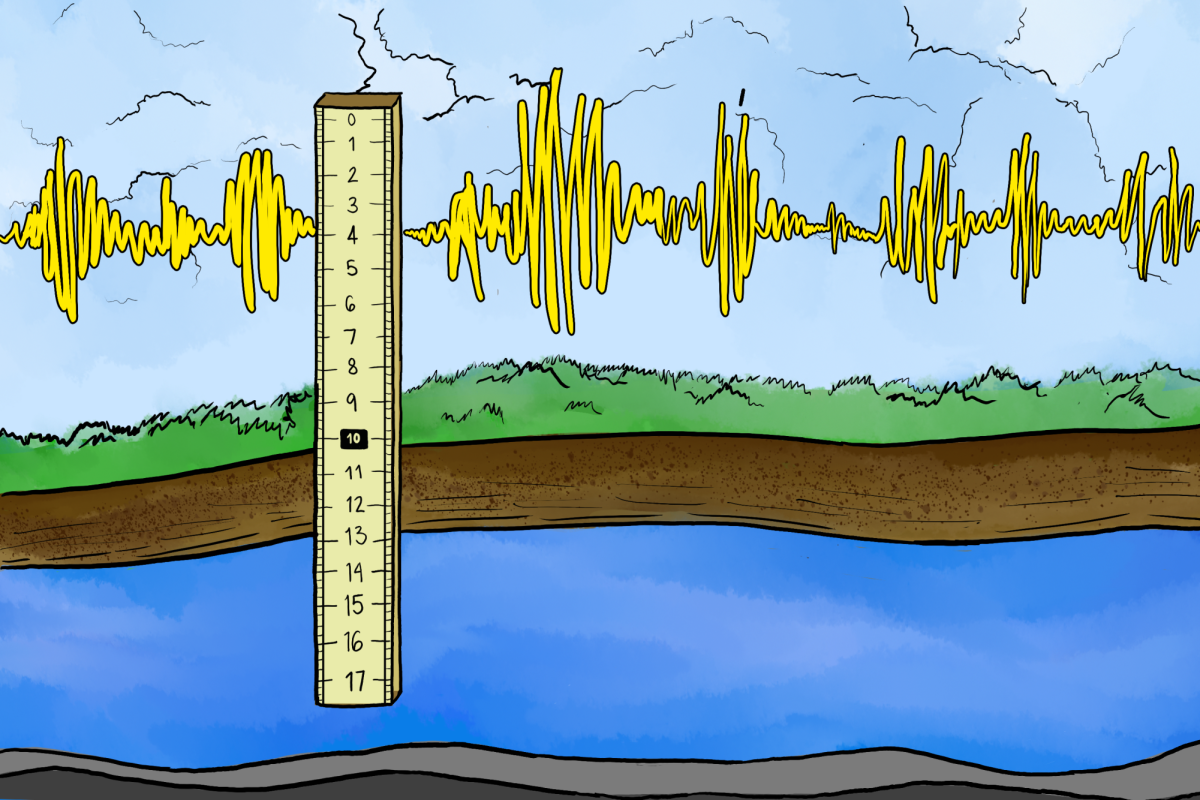

Habitat fragmentation limits the frogs’ ability to ward off the pathogen, and drought-related heat and dryness weaken frogs’ immune systems, Belasen said. Agrochemicals used in land conversion also cause immunosuppression in the amphibians, raising their susceptibility to Bd infection.

The frogs, who now sparsely inhabit California and Oregon, are crucial to the local ecosystems’ success because of the diversity they provide the region and their central position in the food web, according to a UT press release.

Kelly Zamudio, a UT professor of integrative biology who oversees Anat’s work, referred to Bd as “the amphibian killing fungus.” She said researchers plan to utilize immunization and genetically informed breeding as next steps to build frogs’ resistance to the infections.

The proximity of the yellow-legged frogs also increases the spread of disease amongst the species, said Analisa Shields-Estrada, a doctoral candidate in the David Canatella lab in the Ecology, Evolution and Behavior program in the Integrative Biology Department at UT Austin.

“Even if you think of COVID-19 and humans, if we’re all packed in a room together, there’s way more transmission than if we’re all throughout a building.” she said.

Shields-Estrada said frogs are ecological indicators, which means their decline is indicative of a larger issue with the ecosystem as a whole, considering their high sensitivities. Monitoring locations in which frogs or amphibians are in danger as well as building corridors between populations to increase gene flow may help slow the spread. She said paying landowners who live in areas highly populated with amphibians to mimic the species’ natural habitats can help protect the animals.

Belasen said she urges people to vote for representatives who value the environment and science so they can help allocate funding to those doing conservation work. Using less pesticides and fertilizers also can make a difference for local wildlife, she said.

Belasen is currently focusing her research on the genetics of infection rates. If genetic marking is a part of slowing the disease spread, next steps may include captive breeding or re-frogging, which involves bringing more healthy frogs into environments where the population is declining.

Belasen said human and amphibian health are interconnected in a framework called “one health.”

“If we care about human health, which we all do, especially now, we also have to care about ecosystem health and animal health and they’re all going to be impacting each other,” Belasen said.