The Alzheimer’s Association, an organization that supports Alzheimer’s research globally, is funding $1.2 million in research projects across Central Texas, including research grant funding for UT.

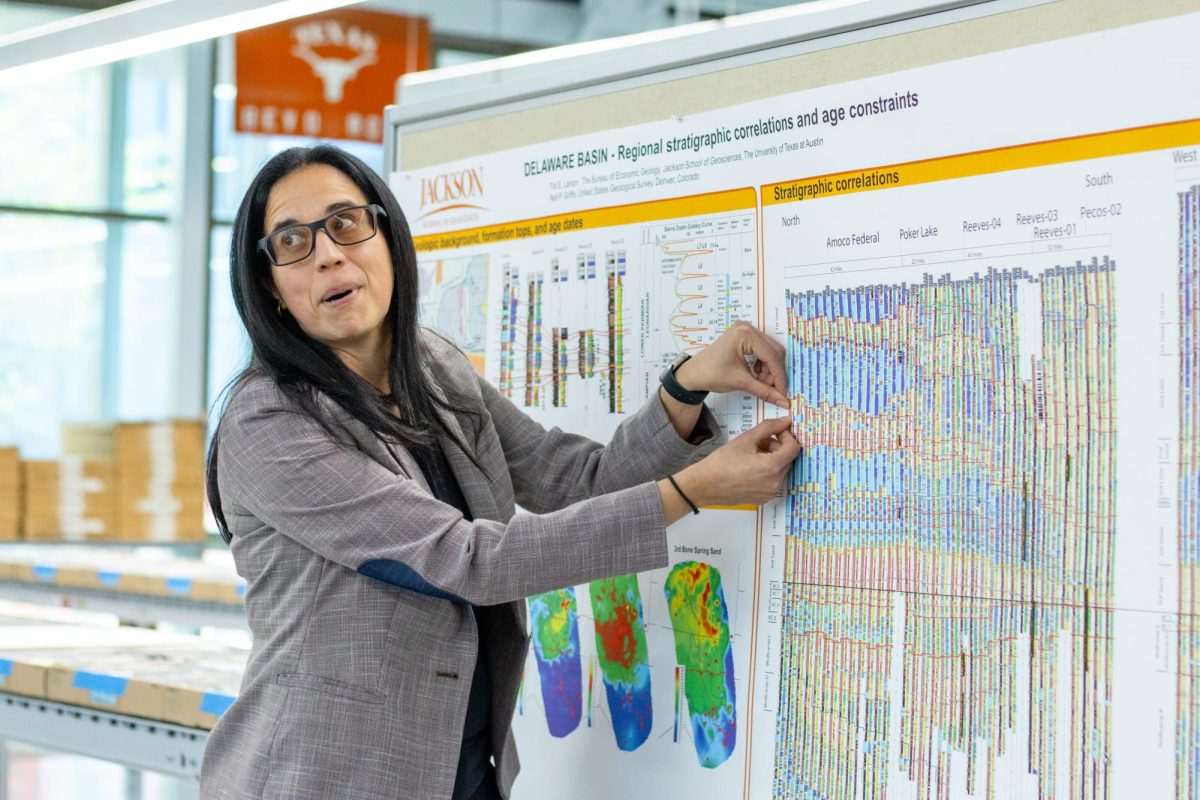

The grant money, awarded to Stephanie Grasso, an assistant professor in speech, language and hearing sciences, and her team, will be used to support people with aphasia, a language disorder inhibiting speech and speech comprehension caused by neurodegenerative diseases. Grasso’s research focuses on evidence-based speech-language impairment in Mexican American and Mexican-origin populations in Central Texas and Mexico.

Grasso and her team will use the grant to recruit 24 individuals with Alzheimer’s-related speech impairments for an online speech training program conducted twice a week over six weeks. Following the program, researchers will evaluate participants’ and caregivers’ satisfaction. The team will also administer speech assessments to measure the program’s impact on speech impairment and use questionnaires to assess quality of life benefits.

“The Association’s funding of $1.2 million in Alzheimer’s and dementia research in Central Texas is not just a financial commitment; it’s a vital step toward unlocking the mysteries of this devastating disease,” said Andrea Taurins, executive director of the Alzheimer’s Association. “With this funding, researchers have the potential to make groundbreaking discoveries that could improve the quality of life for millions of people and ultimately find a cure.”

Grasso said that the project will be an intervention study aimed at addressing speech and language communication challenges Mexican Americans and those of Mexican origin face.

“We know individuals who are Mexican American or of Mexican origin are at a greater risk for developing dementia,” Grasso said. “That’s been a really well-documented pattern that exists.”

Hispanic people are 1.5 times more likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease than white people, according to the Alzheimer’s Association. Aphasia can result from dementia and may cause difficulties such as finding words or constructing complete sentences.

The intervention approach will prioritize cultural considerations, with language viewed as an integral part of culture. The study team includes Spanish-speakers and bilingual members to match participants’ profiles, and Grasso said the team itself is multicultural.

“One of the great things about these intervention approaches that were initially developed in the aphasia lab at UT Austin is really that from its outset, it has been centered on ensuring that the things that we work on in therapy are tailored to the person considering their culture, and it’s interwoven within what we’re doing in the entire therapy approach,” Grasso said.

The therapy steps include simulating a real conversation, practicing scripted content dynamically and promoting the familiarization of words and concepts outside of a clinical setting.

UT researchers will lead participants in speech exercises with common words and practice strategies to remember them, Grasso said. One strategy is showing pictures of items people have trouble naming and practicing descriptions and cues to help recover the words.

“We’re really eager to start using technology to be able to administer and provide these kinds of interventions and strategies that we know that are useful,” Grasso said. “The goal is to provide a culturally sensitive model towards providing individuals with education and support regarding this diagnosis and what they might expect in the future as well as strategies and tools that they can use as care partners.”