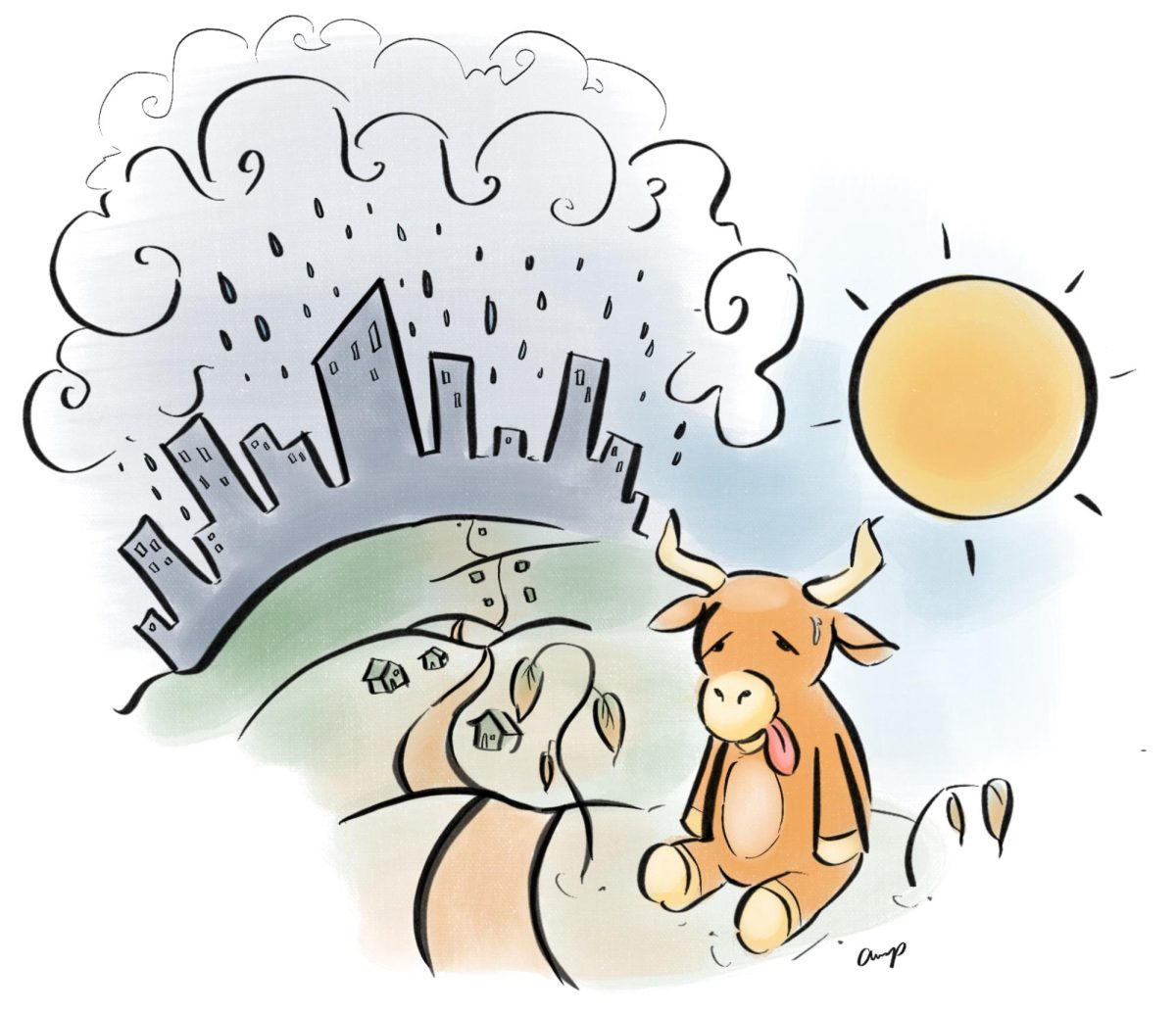

UT researchers discovered over 60% of cities globally receive more rainfall than their rural surroundings, according to a Sept. 9 study.

The study, published by Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, investigated 19 years of satellite data from over 1,000 cities worldwide. It found urbanization causes rapid heating and creates urban heat islands, said Dev Niyogi, chair professor of earth and planetary sciences.

“Cities have a lot of infrastructure … that increases the temperature of the cities,” said Niyogi, the study’s principal investigator. “The surrounding area has just the natural landscape, which does not heat or cool as rapidly as the city, so you have differences in temperature.”

Austin sits on the Balcones Escarpment, a steep slope dividing high Hill Country elevations in the west and low Coastal Plains in the east. Thunderstorms are usually rooted at the surface, however, when they approach Austin from the west, they reach this sharp drop off and fizzle out. This creates a “rain dome,” in which storms are weakened when they reach Austin’s center, then regain strength as they move east.

The city’s location combined with its triangular growth formation means Austin is uniquely affected by the precipitation anomaly, experiencing less storms than other cities.

Xinxin Sui, an author of the study, engineering student and doctoral candidate, said cities with more urban heat island characteristics have larger rainfall anomalies.

“If this urban surface is hotter than the nearby rural environments, more convection will be confined in the atmosphere above the surface,” Sui said.

Sui said climate change is a factor in the precipitation differences, shown through the magnitude of anomalies nearly doubling in the past 20 years. However, Niyogi said the driving reason these anomalies occur is actually population.

“The reality is, as (Austin) grows, even if there is no climate change, just by virtue that it is a bigger city with more concrete, it will be warmer by two to five degrees,” Niyogi said.

Niyogi said more people typically means more development, density, emissions and heat. Clusters of tall buildings can form a heating that can create differences in temperature. This can cause air to converge and create clouds, which absorb pollutants and increase rainfall, he said.

“This is very similar to what happens when you have a salt shaker in a humid area, and you can’t pour the salt because it has absorbed the moisture,” Niyogi said. “It rains when you have enough water in that cloud … and you start getting more likelihood of (rain) in cities.”

Caroline Gamble, an economics, sustainability studies and geography senior and internal director of the Campus Environmental Center, said impervious surfaces such as concrete, which rain cannot penetrate through, worsen the issue and increase flash flood risks.

“The fact that cities have a lack of green spaces … makes flash flooding worse, because there’s not as many places for the water to go naturally,” Gamble said. “That also raises the issue of how lower-income communities usually have less green spaces, which means they are more vulnerable to flash flooding than higher-income spaces.”