Growing up in Austin, Gina Silva always held the University of Texas as a dream in the back of her mind. However, nobody in her family had a driver’s license or a high school diploma. Her mother suffered from drug addiction, and Silva began moving in and out of foster care at only four years old.

“I was a child trying to experience adult responsibilities and emotions,” Silva said. “I had no control over my life.”

When Child Protective Services removed 14-year-old Silva from home, she decided to run away. For years, Silva lived in transitional housing, crowded homeless shelters and on the couches of friends and coworkers. She got a job at H-E-B and picked up as many shifts as possible. Instead of pursuing a GED, Silva enrolled at Round Rock High School.

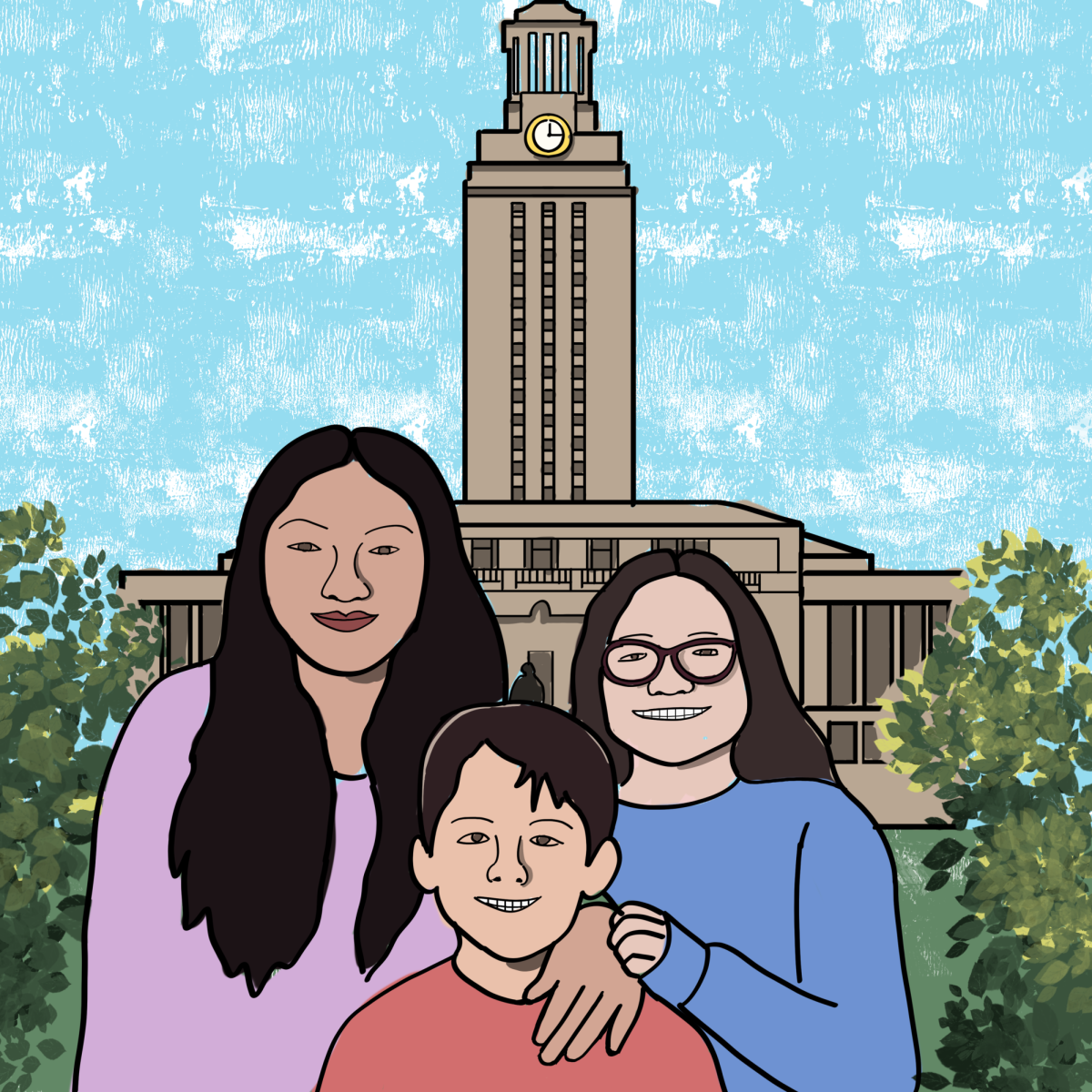

“I knew the goal was to get my brother and sister,” said Silva, who is now a sociology junior at UT. “It had been my goal for a very long time since, probably, the first time we entered foster care.”

Only half of foster youth graduate high school, and only 3% graduate from a four-year college, according to Foster Youth of America. Tymothy Belseth, the program coordinator for the UT Spark Program that provides resources and support to students who previously lived in foster care, said many of these students fear asking for help or aren’t informed about the available resources at the statewide or university level.

“Students in general are facing an enormous amount of challenge and pressure to succeed,” Belseth said. “And let me tell you, being resilient is pretty exhausting. … Sometimes they feel like they can’t ask for help.”

At 16, Silva secured a discounted apartment in North Austin. She caught a bus to school every morning at 6 a.m., the only transportation that would take her all the way to Round Rock. Silva regularly fell asleep at her desk, and her criminal justice teacher Ashley Castro began to ask questions. Slowly, Castro and Silva connected over their hectic childhoods and lack of parental guidance.

“I primarily wanted to teach kids that no matter where you come from, no matter what your background looks like, you can do things that people say you can’t,” Castro said. “That’s why I really resonated with Gina.”

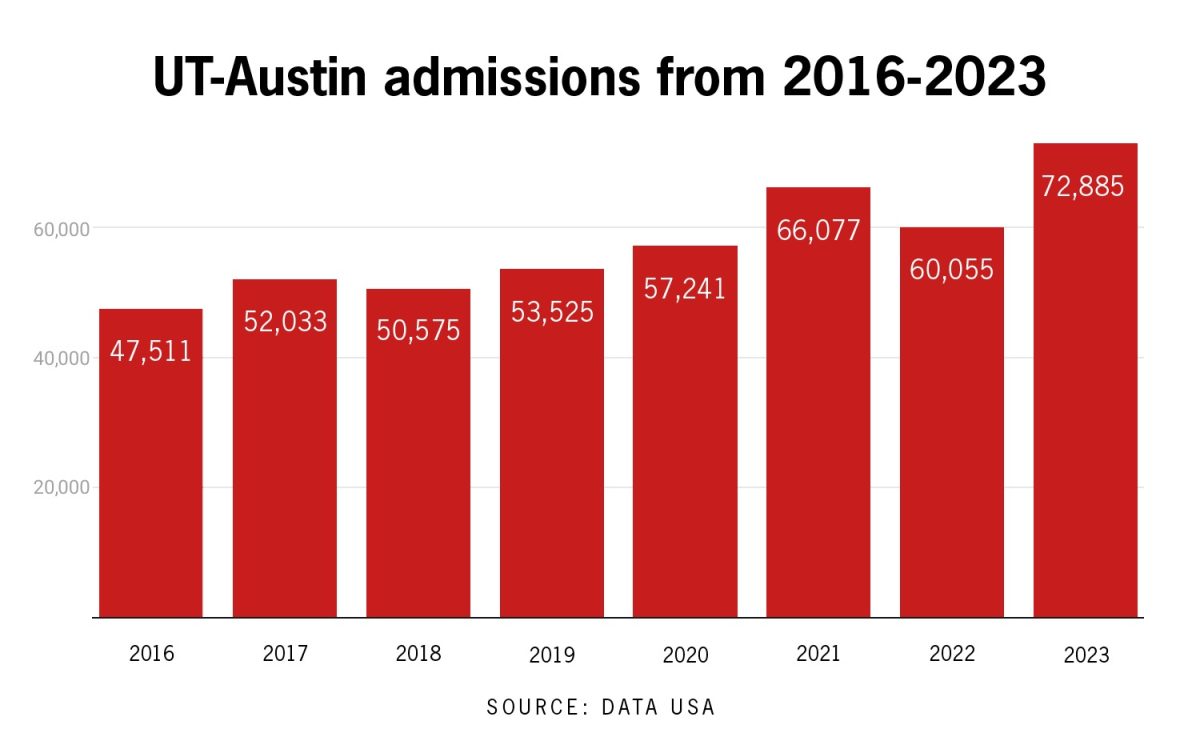

Unfortunately, Silva’s university dream seemed like a stretch to advisors, who warned against applying to a major university. Instead, they suggested taking a gap year or trying community college. Silva listened at first, but on the last day of applications, she frantically applied to the university.

“There’s many (foster youth), myself included, that have absolutely been able to go to college and graduate,” Belseth said. “Many people have told them that they couldn’t do things before, and it’s up to them to be able to prove other

people wrong.”

While she did not get accepted to UT-Austin, Silva received a CAP offer through the Coordinated Admissions Program. That meant she could select any other UT campus for her freshman year with the opportunity to transfer to Austin if she met GPA and course requirements.

Silva chose the first school she saw — UT El Paso — and after two years on the campus, she was accepted into UT-Austin for the fall of 2024. She chose to major in social work to start her path toward law school. Silva said she knew what it was like to be a child in the courtroom and she wants to advocate for foster youth in the future.

A week before moving into her dorm, Silva received a call from her younger sister. Their mother was going back into rehabilitation. Her teenage siblings were alone and squatting in Houston.

“When I found out my siblings were homeless again, I went into panic mode,” Silva said. “I’m nine hours away. I don’t know what to do.”

Her boyfriend drove down to give the siblings a portable stove and blankets until Silva could pick them up herself. With nowhere to stay in Austin, Silva cared for her siblings in a motel, while taking online classes and working full-time at H-E-B. On the brink of the fall semester, her boyfriend helped her secure a discounted apartment.

“Clean up the hotel room. We got somewhere to go,” Silva told her brother and sister. “They were like, ‘Where are we going? Are they kicking us out?’”

Although they had the apartment, Silva said she and her siblings lacked basic necessities and financial stability. Castro started a GoFundMe for Silva at the end of August, and donations poured in online. Now the fundraiser stands at just over $6,000. Community members pooled together enough money for a new car.

“They came through for my brother and sister,” Silva said. “I knew I could provide for them, but I was scared that I wasn’t going to be able to give them the life that they deserved.”

Finding resources for grocery money, textbooks and apartment deposits can be difficult, but Belseth said UT Spark helps alleviate the balancing act of financial and mental stability. Spark also offers mentorship and counseling, as well as peer support groups with fellow foster youth.

“The most important resource that we provide them isn’t a monetary resource,” Belseth said. “It’s a relational resource, being able to connect with people and help people navigate things.”

While Silva received the state’s tuition waiver for foster youth, she remained unaware of the many resources within Texas and the University. In Texas, foster youth can get education training vouchers and affirmative action for government jobs.

“By law, public schools in Texas are required to have an understanding of all of these things,” Belseth said. “Foster parents are supposed to know. Caseworkers are supposed to know, but I’ve met lots of people in the child welfare field that don’t.”

Silva drops her siblings off at school every morning before driving to the University, listening to recordings of her class notes on the way. After classes, she picks up her siblings and works at H-E-B the rest of the day.

Silva said she acts as both a sister and a mom. She purchased a homecoming mum for her sister, but she also takes away their phones sometimes. Silva studies for class while her sister sits beside her filling out college applications. Her brother also hopes to attend a trade school or get a degree.

“I really want an emphasis on graduation, because (my sister) is also a first-gen,” Silva said. “She’ll be the second person in our entire family to go to college. I’m trying to help her navigate it.”