An analysis of the skull of the roughly 69-million-year-old Vegavis iaai bird provided insight into the species’ place on the evolutionary tree of birds, UT researchers said in a collaborative study published on Feb. 5 with researchers and experts from across the nation.

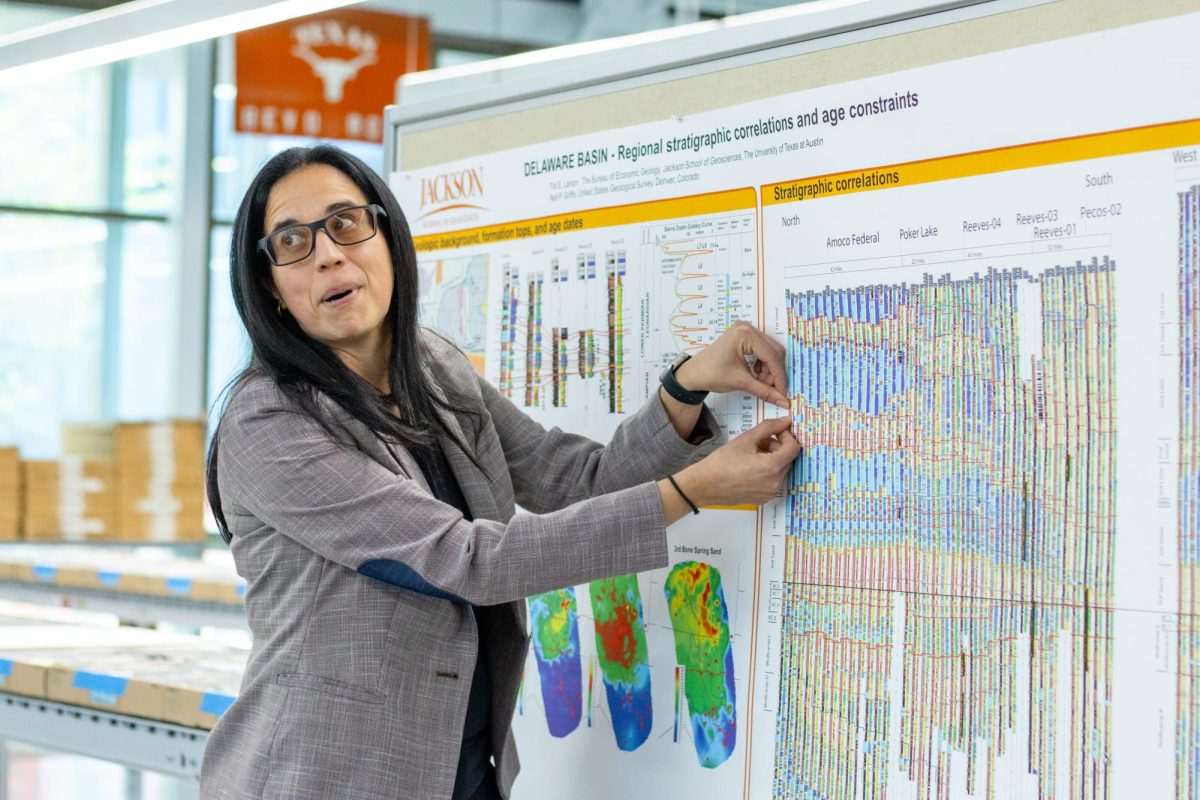

Julia Clarke, a Jackson School of Geosciences professor, helped discover a V. iaai specimen in 1992 and named the species in 2005. She said she initially hypothesized that the species was closely related to modern ducks on the evolutionary tree of birds, but other scientists disagreed. This most recent study is “consistent” with Clarke’s initial hypothesis, she said.

“The point of science is you get new data, and you’re willing to revisit your prior analysis and prior finding,” Clarke said. “This was a new big chunk of data on the skull, which we’d never had, and the brain, which we’d never had, and it helps us place (the V. iaai) within living birds.”

Clarke said she had published two other papers on the V. iaai bird but was especially proud of how, in this study, the lead author was a former student of hers.

“What is different and exciting to me about this paper is that this is my student who’s now taking the lead on this work, and to see someone, (a) UT graduate, go off and do an exceptional job with this has been phenomenal,” Clarke said.

Chris Torres, the study’s lead author and an assistant professor at the University of the Pacific, began the research as a doctoral candidate at UT, with Clarke as one of his co-advisors. Torres said he was able to use the inside of the bird skull as a mold to reconstruct the external surface of the V. iaai bird’s brain, which provided new data on the bird.

“It’s not a pre-modern bird, and therefore we can recognize it for having the significance that it has for our ability to even begin to investigate processes (related to) extinction and survival dynamics,” Torres said.

Torres said the finding did more than just illuminate the past. He said discoveries of fossils can help society understand extinction events and how the world has changed and could continue to do so in the future.

“There’s a good chance that what we are witnessing happening in the world today is another one of those events, another event that could shape the world for tens of millions of years,” Torres said. “If we want to even pretend to have an idea about what’s coming, we need to study the fossil record.”