A plant’s immune response to pathogens can cross-regulate the plant’s growth development, UT researchers and collaborators published in a Feb. 5 study.

Plants contain pores called stomata that allow the plant to absorb nutrients and excrete waste, said Keiko Torii, co-author of the study and principal investigator of the UT team. Torii said the stomata need enough space to open and close so the plant can respond to its environment and either grow or conserve resources. She said the plant cells signal to each other where the stomata will be.

Torii said the communication networks of immunity and growth development normally remain separate to “avoid misinformation.” However, the team uncovered that the immune pathway can regulate the number of stomata in some situations.

In experiments, the team introduced a chemical that interfered with the plant’s growth development and resulted in an unhealthy increase in stomata. The team then introduced a pathogen that triggered an immune response from the plant. This immune response regulated stomata development, counteracting the effect of the chemical by reducing the number of stomata, Torii said. She also said the immune response might do this in order to reduce the number of potential entryways for the pathogen.

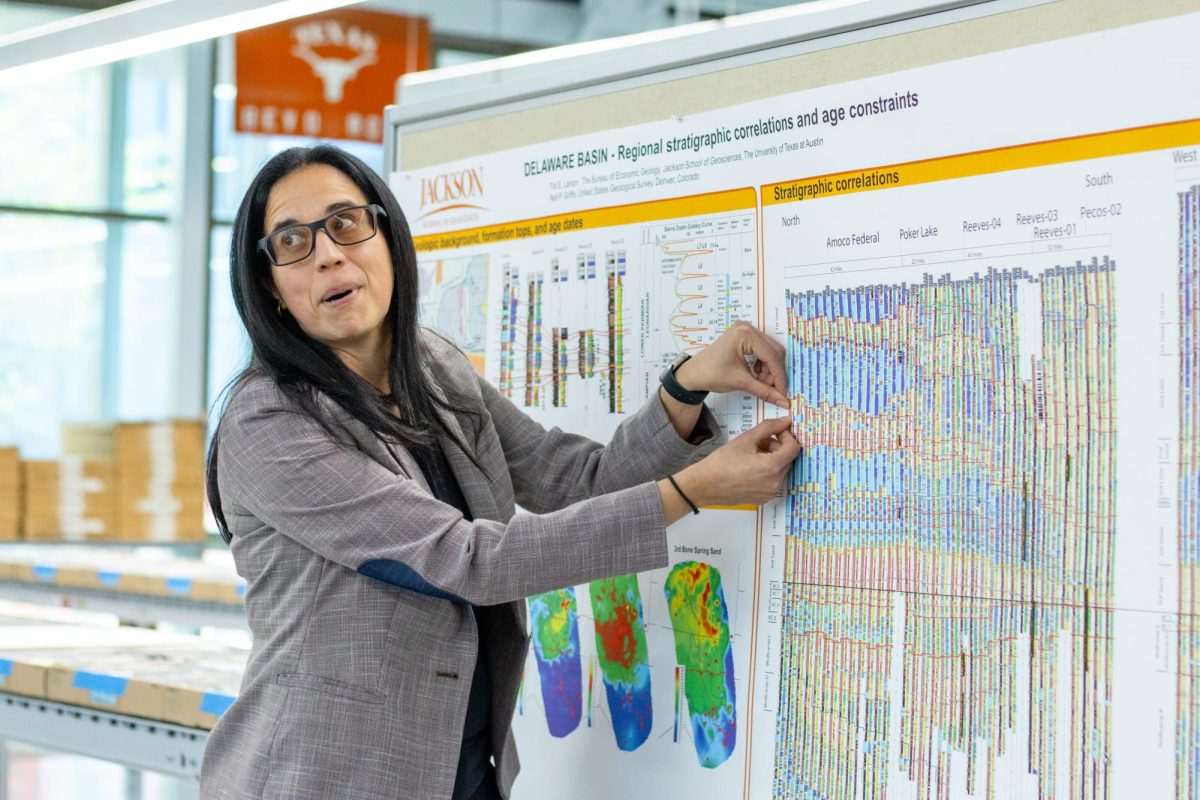

A distance in time exists between the research and its practical application, but in the future, the research could have implications for producing high-yield crops, said Krishna Sepuru, a staff scientist and co-author. Torii said the trade-off between fast-growing versus resilient crops is a problem for breeders, and this research could help breeders manage the plant’s growth and immune system defense.

“When plants are defending, they don’t grow, and when they are growing, they cannot defend because they can do either one or the other,” Torii said. “How to break or manipulate that (trade-off) to increase the plant resilience and also make them defend well … is becoming (a) huge interest worldwide in plant biology or group science.”