Since the pandemic, student reading levels have dropped, showing little sign of recovery. Now, professors must find ways to adapt classes to changing student needs by cutting down on reading assignments and utilizing online resources.

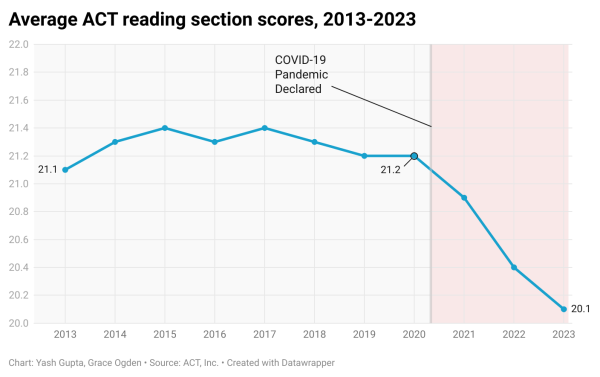

For nearly 30 years, ACT reading results remained above 21 points. In the years following the pandemic, average ACT reading scores fell from 21.2 in 2019 to 20.1 in 2023, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. This decline, which likely indicates weaker reading comprehension skills among incoming college students, means many professors feel the pressure to change class expectations.

But UT English professor Gretchen Murphy said the present moment poses a new challenge for professors and is not something to fear.

“I would be very sad if I believed we were actually losing the ability to lose yourself in a book, to be caught up in a gripping story, to read with attention,” Murphy said. “I don’t believe that we are losing those things, but I think people are learning to read in a lot of different ways (with) visual culture (and) different kinds of media.”

Gina Bastone, a UT humanities librarian, said the university’s growing online collection proves increasingly vital for students today, who tend to lean on online resources.

“It’s a 20-plus year shift that we’re in the middle of, that I don’t think is over yet, between print and digital, online collections,” Bastone said.

English professor Douglas Bruster said he believes the issue started just after the release of the first iPhone in 2007. Around this time, he said he began to notice “slow changes in students’ patience” with reading material.

“Not only were the phones quite widespread, but they became so much a part of people’s lives that they were like appendages,” Bruster said. “You wouldn’t ever think of leaving (a phone) behind because it was just part of who you were.”

In the following years, he said that a growing number of students began approaching him after class to ask him if he really knew how long Hamlet was when he assigned it. Still, Bruster rejects the idea that shifting reading habits reflect a shortcoming in students. Instead, he encourages educators to work with students to prepare for the coming years.

“It’s not a moral failure,” Bruster said. “I’m not reading this as something wrong with students today. That’s not helpful. We need to work with the students we have, and to prepare you for the world that’s out there today, but also the world that’s going to be changing all the time.”

Bruster said that part of the issue is that students today engage with more video content than ever, a reality that he said professors must accept. As of March 2025, YouTube has over 2.7 billion monthly active users, according to Global Media Insight. On TikTok, one of the largest social media sites today, users spend an average of an hour and a half per day on the app, according to SensorTower.

“The worst thing that we can do is to lament a world that’s going to be really hard to recover and to complain about things that students really don’t have in their control,” Bruster said. “We need to be responsive to all of our students’ needs.”

Due to the mounting concern from students regarding the sheer amount of reading, Bruster began starting classes each semester with a disclaimer warning students of the length and difficulty of reading assignments.

“I try to diffuse people’s anxiety by having us all as a class do a few lines of Middle English together,” Bruster said. “I also say, ‘Look, I want you to read this poem, but there are audiobook versions of this on YouTube and elsewhere.’”

Librarians like Bastone and Sarah Brandt said that the solution may mean embracing current student reading habits like e-books. According to data from Pew Research Center, 30% of Americans now read e-books.

Bastone said she uses the term “agnostic” to describe her approach to student reading, meaning she wants students to read in whatever form they prefer.

“If the e-book is what works best for them, I want them to get the e-book,” Bastone said. “If the print book is what’s best for them, I want them to get the print book. We need to figure out on our end how to make that happen, whether that’s through money, whether that’s through staffing, whether that’s through physical space in the library.”

Worried about keeping students updated on materials for discussions, Murphy built reading quizzes into her classes years ago. She said that over the course of her career, but most notably in the years following the pandemic, she has assigned less and less reading.

“Over time, you learn that more is not always more,” Murphy said. “Making sure that everybody can really complete the reading assignment and do it with any degree of attention is more important than making sure the syllabus is chock-full of everything we could possibly be reading.”

Brandt said cutting down on reading allows professors to evaluate course expectations. She said that shifting the focus away from quantity lends itself to more time in class to “talk through each piece, versus having so much … but (there’s) less time.”

According to Bruster, reducing reading loads is nothing new. When he began teaching at UT in 1999, Bruster said he assigned 10 plays each semester. Now, he limits it to six.

“Six is a pretty good compromise for me,” Bruster said. “You have to teach the students you have, and you have to decide where to pick your battles and what’s valuable to you. What’s valuable to me is reading complex books in their original language and having meaningful conversations about them. I’ve been lucky that I could do it here at UT, and I recognize that students are changing.”

Reducing required readings may, in theory, appear to make classes easier. However, Murphy said that shortening reading assignments may not necessarily make classes less rigorous.

“What we’re doing in English (classes) is often critical thinking, learning close reading skills, learning how to research, learning how to pull meaning out of something, to personally reflect on it,” Murphy said. “You can do that with a poem that’s five lines long and you can do that with a novel. So the real question is, how much time outside of class is going to be spent reading this novel? You’re not actually cutting back on what people can get out of class by using shorter readings.”

As Bruster noticed a growing number of students struggling with reading, he developed several techniques to engage students with assigned material.

“These days, I might recommend reading with an audiobook playing at the same time. Or if I’m teaching, say, a Shakespeare play, (I suggest they) fire up the BBC Shakespeare online from our library homepage and turn on the closed captions,” Bruster said. “That can be a really effective way of getting the verse and the prose into your head by listening and watching an actor perform the lines while you read them at the same time.”

Bruster said that, ultimately, a strong visual education should be complemented by reading.

“There’s really no reason to put the moving image and the written word into enmity with each other,” he said. “We’ve got to figure out ways to work both of them into our teaching and to help our students succeed as best as we can, using every single tool that we’ve got.”