Hours after President Donald Trump’s inauguration on Jan. 20, he signed 26 executive orders, including four directives following through on the administration’s stated commitment to cut back on renewable energy policies, protection of natural resources and federal climate science efforts.

In 2023, 67.7% of all research funding at UT came from federal sources, accounting for over $640 million, according to data from the UT System Dashboard. The University of Texas System is second in the U.S. for federal research expenditures, according to a press release from April 2024.

Ingrid Kolb, acting secretary of the Department of Energy, said in a Jan. 20 memorandum that the Trump administration froze all spending at the department, including the distribution of research grants, according to Bloomberg. The freeze was part of a “comprehensive review” of ongoing projects to ensure they align with the Trump administration’s priorities.

Trump’s actions are reminiscent of funding cuts for 73 federal programs that he proposed in 2021, some of which included key science agencies such as the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Environmental Protection Agency and the Department of Energy.

Joshua Busby, a professor in the LBJ School of Public Affairs, said in an email that administrative action towards funding through the Inflation Reduction Act would be likely — specifically, for projects supporting clean energy.

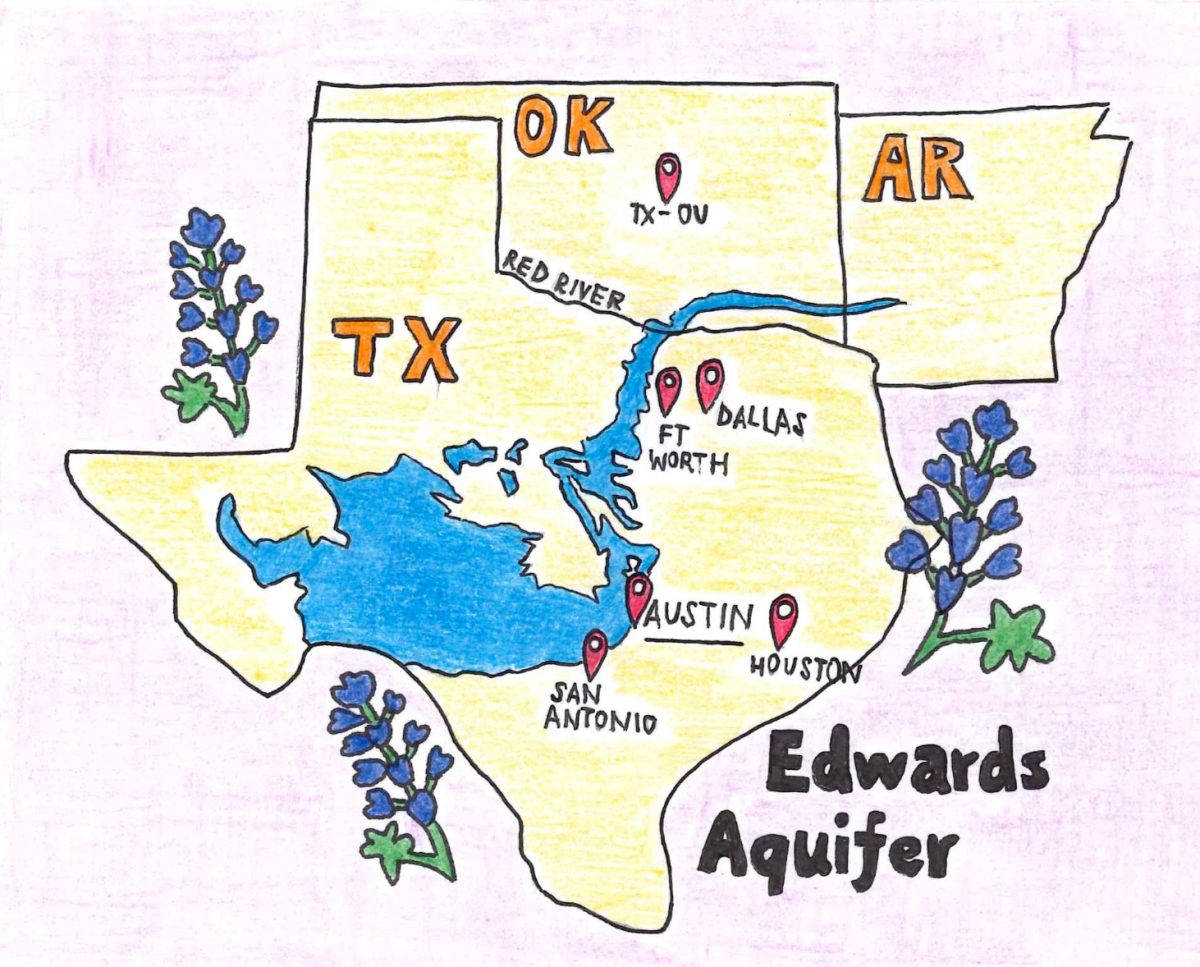

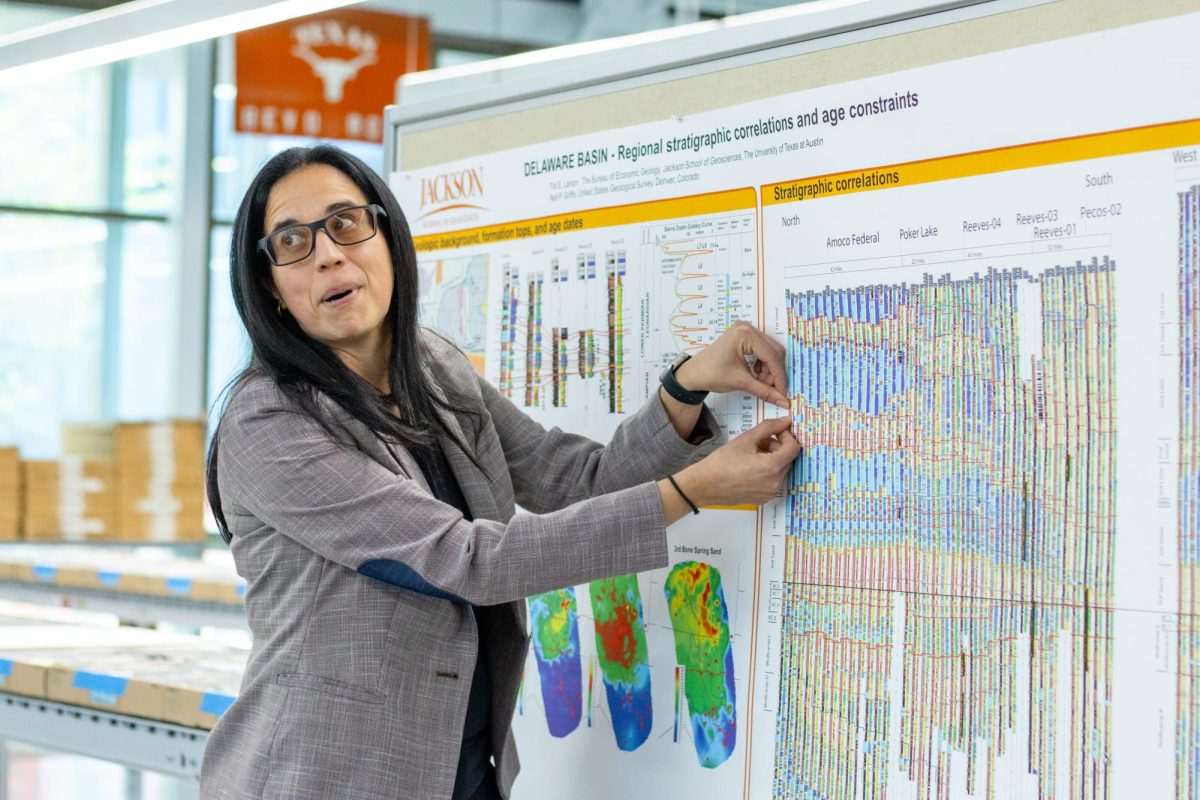

The 2022 act increased the 45Q tax credit designed to incentivize investment in climate solutions, such as carbon capture storage. Carbon capture storage involves capturing carbon dioxide emissions directly from the source of emission, such as a factory, and storing it permanently in the Earth’s subsurface.

Alex Bump, research science associate at the Gulf Coast Carbon Center, said the credit increase helped generate bipartisan interest in carbon capture storage.

Last year, Bump and his team were awarded $5 million for a project advancing carbon capture and storage along the Gulf Coast. He said carbon capture storage is a precautionary strategy to mitigate climate risk.

“It’s not the cheapest solution in many cases,” Bump said. “But, you can apply it to just about any (carbon dioxide) source … it’s a useful technology to have to be deployed where needed.”

It remains uncertain how projects already selected for energy department funding will proceed following the spending freeze.

Bump said public awareness of carbon capture storage is still low, raising concerns about its effectiveness and cost.

“This is a policy debate about where you put money, but keeping options in the mix as strategic risk management makes a lot of sense,” Bump said.

The framing of climate science, particularly, how climate research is received by the public and influences policy decisions has changed over time, according to Megan Raby, associate professor in history.

“Into the 90s, scientists were really reticent to be political because they were afraid people would accuse them of being biased,” Raby said.

While there is increased consensus that the effects of climate change have worsened because of human activity, Raby said climate research has been poorly received by both the government and the American public. Raby said the trend of climate denialism still continues.

“Scientists have long been trained as part of the scientific tradition; their job is to figure out how nature works, and if there’s a policy application, they bring it to the public,” Raby said. “They bring it to the people who are supposed to protect the public — the government.”