The one thing computers can’t get right is out of this world — literally.

UT astronomer Justin Spilker worked alongside various researchers across the globe to uncover the secret to a self-sustained, billion-year-old galaxy: wind. Computer models weren’t effective in modeling galaxy growth, Spilker said, so he used the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array of telescopes in Chile to get a high-resolution look at what really happens during the formation of galaxies.

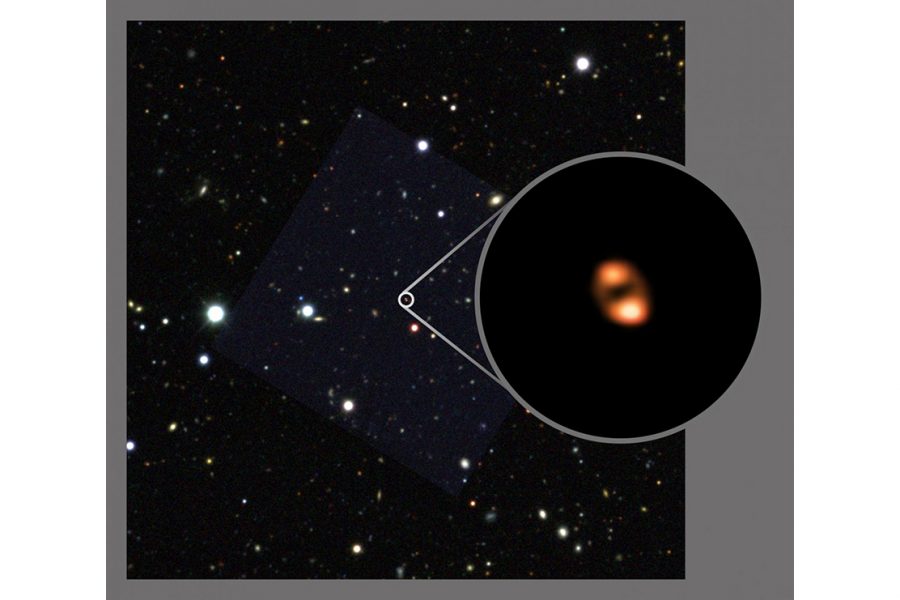

“By cosmic coincidence, there happens to be another galaxy lined up between us and the background galaxy that we care about,” Spilker said. “It’s basically like us … this galaxy in the foreground and then the background galaxy … all in a line. It (the foreground galaxy) makes the background galaxy look brighter than it usually would be … it gets a more high-resolution picture.”

With more accurate imaging, scientists could see jets of energy protruding out from the galaxies. Scientifically known as outflowing, this galactic “wind” observed by scientists allows galaxies to self-regulate growth or create stars slowly over time instead of all at once, in a process quite similar to the water cycle on Earth, Spilker said.

“The sun sucks water up, and it goes into the atmosphere, and then it cools, condenses and makes clouds, and then those clouds will rain,” Spilker said. “That’s how the water gets back down to Earth. It’s a similar story for galaxies.”

Spilker said energy for this heating and cooling cycle comes from two main processes: the explosion of a large star and its subsequent release of energy, called a supernova, and the presence of matter near a black hole. Most galaxies, including our own, have a black hole in their center. The heat of friction as materials swirl around the opening of a black hole produces a lot of energy, which has the potential to drive outflows, Spilker said.

“You dump all this energy into gas in the galaxy, and that drives this outflow so it goes shooting off up into the halo of the galaxy,” Spilker said. “But in order for it to come back down, it has to cool and condense into these denser cloud-like structures. What you end up with is a fountain of material shot out of the galaxy and then it lives in the halo of the galaxy for a long time.”

Since the gas is no longer in the galaxy, it is unable to form more stars, Spilker said, which allows the galaxy to regulate its growth in early stages of creation. Older galaxies stopped forming stars long ago and haven’t started again, he added. This raises the question for astronomers of whether or not outflows of energy are able to keep stars from forming in galaxies for long time spans, Spilker said.

Spilker’s findings were published in the journal Science in September 2018.