Red, white and blue lights flashed outside of Natalia’s apartment, as she voluntarily got into a cop car, pulled out her phone and loaded UT Canvas to notify her professors of her suicide attempt.

“I guess I kind of thought that was my responsibility to tell them because it was my fault I was going to the hospital,” Natalia said. “… I didn’t know what UT would do for me just as a person (and) as a student. I didn’t know how far they extended their reach.”

Natalia described her episode as a “full-on, unprovoked mental breakdown,” due to severe depression combined with work and relationship stresses. As Natalia was getting ready to go through with the attempt, a friend intervened and told Natalia to call the cops.

Natalia was admitted to a mental hospital on March 18 and received treatment for one week. Natalia has asked The Daily Texan to withhold her year, major and last name for anonymity purposes. She is currently a student at UT.

If a student attempts suicide and is hospitalized, professors will be notified by Student Emergency Services that a medical emergency has taken place, as with any other type of student hospitalization. UT students have to notify their professors of a suicide attempt on their own unless the student asks to sign a release of information with Student Emergency Services, allowing the office to inform professors for the student, said Sara Kennedy, spokesperson for the Office of the Dean of Students.

It is up to faculty discretion as to whether or not to excuse the student for the missed class dates due to the attempt.

This blanket notification to professors is in place to protect the confidentiality of survivors who don’t wish to disclose the details of their attempts to their professors, said SES director Kelly Soucy.

“We leave it up to the individual student to tell us how much they are comfortable with sharing,” Soucy said. “If a student wants us to help them have that conversation with a faculty member, we’ll do what we can to support them.”

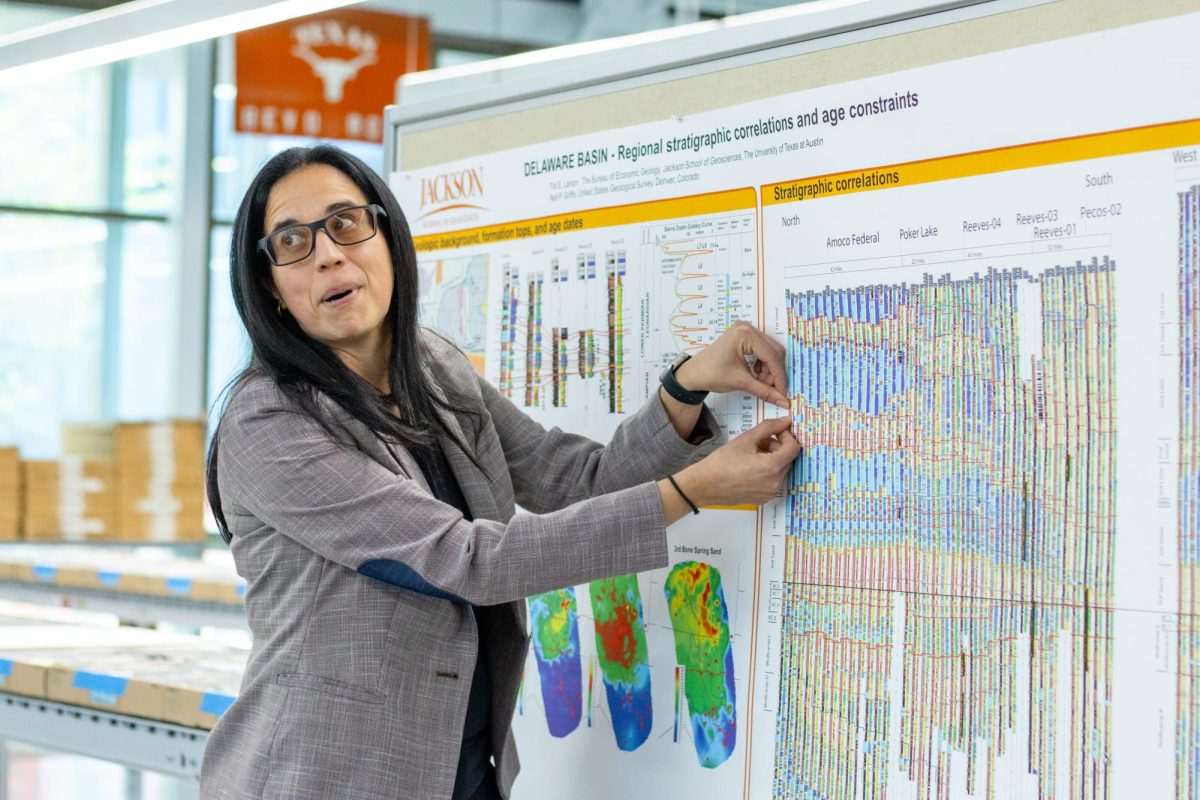

SES can be notified of a student’s mental health-related emergency by Austin-area hospitals and emergency rooms, the University of Texas Police Department or UT’s Counseling and Mental Health Center, CMHC Director Chris Brownson said.

April Foreman, licensed psychologist and board member for the American Association of Suicidology, said it is perfectly legal for a university to offer an optional release of information for students seeking to tell professors about a suicide attempt.

“What we would want is a policy that respects their confidentiality,” Foreman said. “Then also, we would want practices that respect their autonomy and talks with them about what they need relative to their suicide attempt and their recovery and the best way to go about it.”

Natalia said she met with SES the day she returned to class after being released from the hospital but didn’t understand what counseling services were available following the meeting. After her initial week back to UT after being in the hospital, Natalia said she didn’t hear from the University again for any follow-ups on her suicidality.

“I don’t want to feel like a statistic,” Natalia said. “What I’ve noticed is the stress of (the time) after a suicide attempt just kind of makes it worse because you start thinking, ‘Oh, if I had been successful, none of this would’ve been happening.’”

Suicide is the second leading cause of death among college students. Brownson said about three students at UT will commit suicide every year. Nationally, 8 percent of undergraduate students and 5 percent of graduate students have attempted suicide at some point in their lives, according to the CMHC website. Suicide attempt rates present a research challenge, because they are self-identified by the individual, Brownson said.

“The period after a hospitalization, for example, is one of the highest risk periods for suicide,” Brownson said. “It is very important that students are getting connected with the help that they need after an attempt.”

Foreman said, ideally, the student counseling center should have a point of contact trained in suicide care to help readjust survivors back to daily life.

“You don’t write that necessarily down in a policy,” Foreman said. “What you do is you have a practice. Your policy says who’s going to follow up with the student, but the practice is how you behave in a variety of circumstances that honor basic ethical principles.”

At the University of Illinois, students recovering from an attempt are mandated to attend four weekly professional assessments of their suicidality upon returning to university. A hospital visit may excuse one of these assessments, but the policy is in place for support.

“Around 80 percent of students who die by suicide never had contact with a counselor,” said Christopher Lofton, care manager at the University of Illinois counseling center. “If people on our campus are in contact with students who might be going through something, we want to make sure that the student at least knows about the counseling center and is connected to us.”

UT is one of the few university counseling centers that has an active relationship with a nearby hospital, Brownson said. Seton Hospital sends two staff members to UT to host an intensive outpatient program for recovering students to opt in to.

“Intensive outpatient programs are typically three hours of psychotherapy a day, four days a week,” Brownson said. “That’s a way we can keep students in school so they are less likely to have to drop out and still getting that kind of treatment and support that they need.”

‘Be That One’ is UT’s suicide prevention program that aims to prevent suicide on campus by raising awareness, empowering faculty, staff and students and ensuring the University is supportive of students and their mental health needs, said CMHC spokesperson Katy Redd. CMHC offers a 24/7 confidential crisis line for UT students to speak with trained counselors about urgent needs, similar to the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline.

Natalia had to drop an online class and is retaking another class because she failed the test the week after coming back from the hospital. Natalia said she thinks she is going to have to take an extra semester due to her attempt.

“It’s OK to get help,” Natalia said. “I don’t know why there’s this stigma about getting help …. Getting help is the best thing you can do. (Suicide) might end your grief, but it just extends it on your friends and family.”