MIDLAND — For many years, the landscape in West Texas was mostly uniform with dusty lots and artifacts of operating machinery left behind from a previous oil boom in the area. A generation removed from that boom, new oil rigs line roadways in the Permian Basin, where increased production will help the UT System bring in close to $1 billion in oil and gas revenue this year.

With a technologically driven oil-production boom, Midland’s landscape is transforming as the city works to build an infrastructure to support thousands of new residents while reaping the economic benefits associated with increased production. The UT System is also benefiting from the economic boom, and it doesn’t show signs of slowing down as dozens of companies have showed renewed interest in chasing the oil reserves on the 1.4 million acres the System has in the region.

Last October marked the first time land managed by the UT System produced more than 3 million barrels of oil since 1972 at the peak of the last oil production boom in the Permian Basin, said Jim Benson, executive director of University Lands.

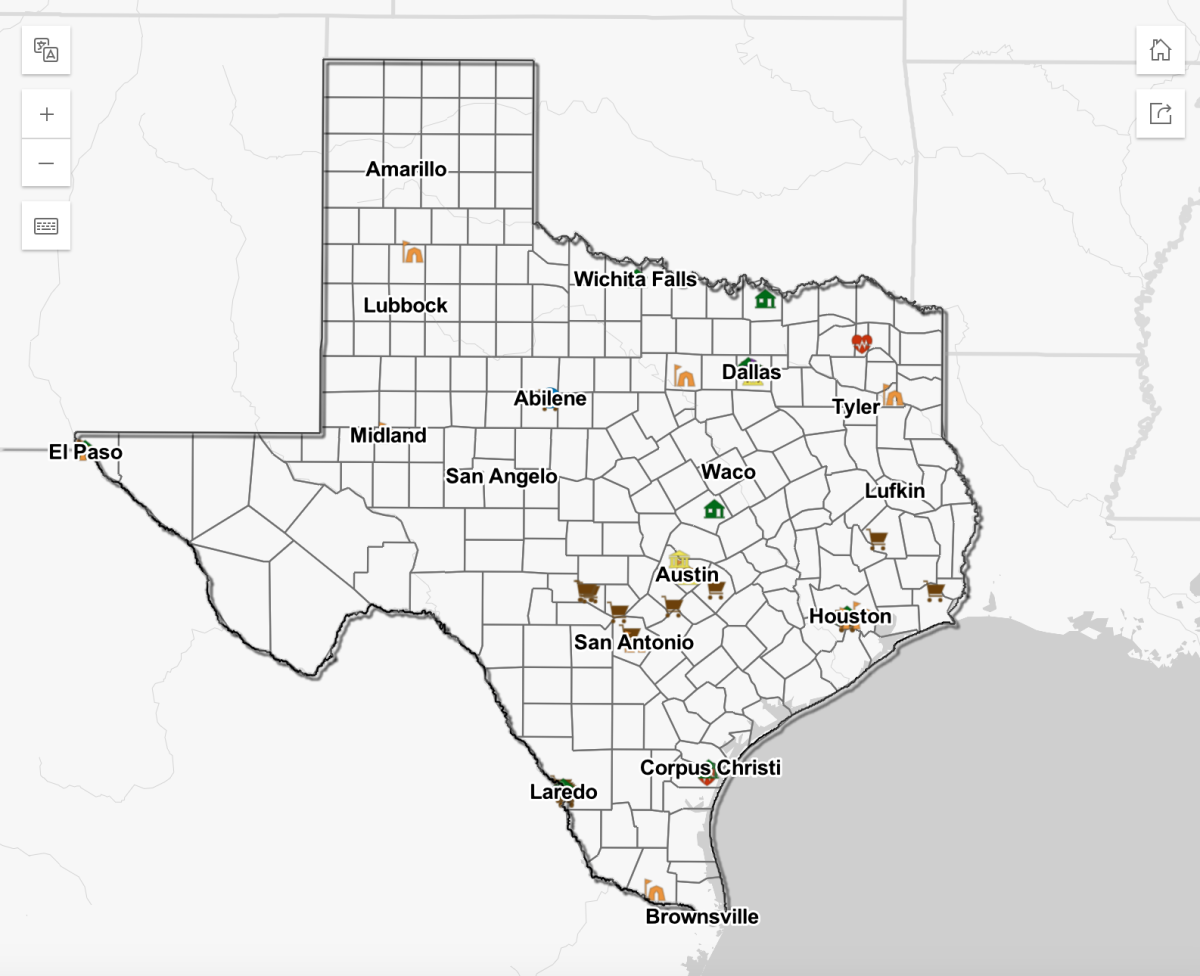

University Lands, which has a Midland-based office, is responsible for managing the System’s 2.1 million acres that make up the Permanent University Fund.

The surge in production is part of a massive oil boom under the Wolfcamp Shale formation accessible through drilling technologies and techniques — horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing — that were not commonly used during the last boom in the area.

“This kind of changed everybody’s mind-sets to, ‘Now, we can go produce these source rocks or unconventional plays,’” Benson said. “That is what’s happening in the resurrection of the Permian Basin.”

With 50 oil and gas rigs actively drilling, 25-50 wells being assembled and 500 more permits waiting to be built on its land, Benson said University Lands still stands to increase its profits in the next two years as oil and gas companies leasing on the System’s land in the Permian Basin move into full manufacturing mode by 2015.

“Even though there’s not a lot of manufacturing, there is a lot of capital expense, and our revenues are increasing in terms of the royalty rate,” Benson said. “Two years down the road, provided oil and gas prices stay as they are, we’ll make more than we did in the previous years.”

The Texas Railroad Commission defines the Permian Basin as an oil and gas producing area in West Texas 250 by 300 miles in area.

Benson said he expects University Lands to receive $850 million in royalties from production on leased land on top of the $112 million the System received in lease sale profits in the last fiscal year.

In the last five years, the number of drilling permits approved by the Railroad Commission in the Permian Basin has almost doubled, increasing from 4,703 in 2007 to 9,3335 in 2012, according to Railroad Commission figures.

Oil and gas lease sales first skyrocketed during the September 2010 sale as the boom took off with total profits increasing during the following two sales, including a record high sale in September 2011 that brought in more than $310 million in profits.

The University of Texas Investment Management Company invests the sale profits and royalties and returns on investment make up the Available University Fund, which benefits the UT and Texas A&M systems. Last year, $205 million of UT-Austin’s $2.34 billion 2012-2013 operating budget came from the fund.

Profits from subsequent sales decreased substantially because fewer acres were available to be leased as companies jumped to lease in 2010 and 2011 when the boom picked up, Benson said. The most recent sale made only $70 million with about 16 percent of the acreage up for lease during the September 2011 sale.

Oil was first discovered on UT lands in 1923, and the lands in the Permian Basin saw high levels of production during an oil boom in in the 1960s, during which the entire area produced 607 million barrels of oil over several years, according to the Texas State Historical Association.

Overall production in the basin totaled 312 million barrels of oil just last year, according to Railroad Commission figures. Production on University Lands, which fall mostly in the Permian Basin, reached 32 million barrels of oil in 2012 alone.

Development and challenges

In a city where pump jacks are as common in backyards as swing sets, millions of gallons of water are being used per well for fracking. Despite a long-standing drought in the area, most locals’ concerns revolve around increased traffic and the faster-paced lifestyle that has resulted from the oil-driven migration to Midland.

In 2005, the city’s population stood at about 99,000, according to city estimates. According to the U.S. Census estimates, the population stood at about 114,000 in 2011.

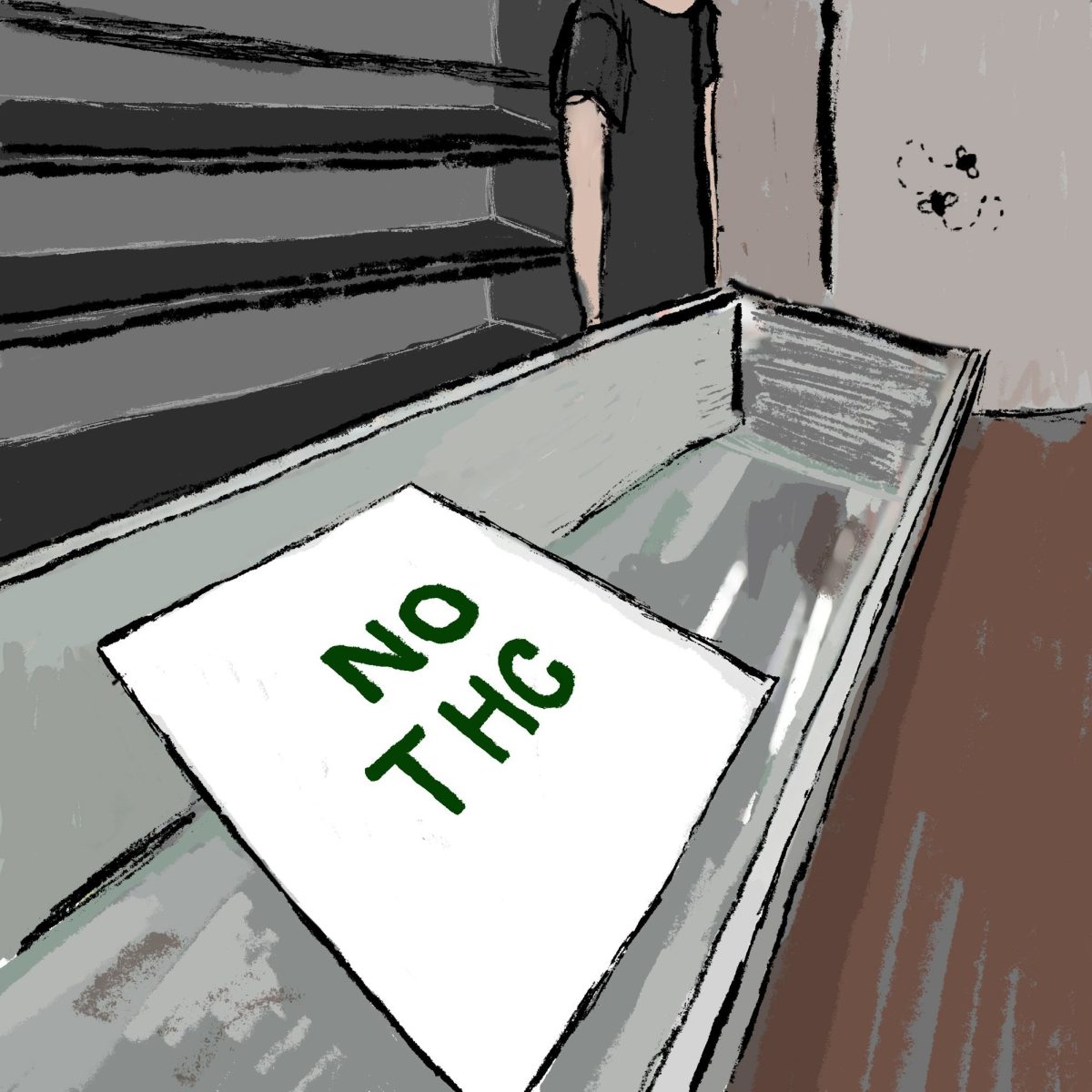

Some locals complain about the lack of supplies in grocery stores. A trip to the local Wal-Mart proves that multiple aisles have completely empty sections, including bottled water, raw chicken, sports drinks and toilet paper. Others complain about increased traffic in the area as travel time increases and major streets and roadways become a caravan of large oil transportation trucks and Super Duty Ford trucks emblazoned with oil and gas company logos.

Midland Mayor Wes Perry said the technology behind the current oil boom is essential to development in the area because it has boosted sales tax revenue, which the city is using for one-time capital projects after seeing increases in sales taxes.

“At this particular time, it’s not the typical situation like we had it in the past because it is driven by technology, not so much the price of oil,” Perry said. “When the price of oil drops, things will slow down, but it’s not going to be like it used to be where it was a boom and then a big bust cycle.”

Midland is currently undergoing various development projects to improve infrastructure, including highway widening projects and waterline extensions to industrial areas.

The increase of oil workers in the area has also transformed the city’s skyline with the construction of dozens of new hotels, which bring in hundreds of thousands of dollars in revenue for the city.

Perry said private sector developers are taking advantage of the financial opportunity in the housing market, which has faced increased levels in demand. Available and upcoming housing in Midland is projected at 5,300 available units, including 2,079 apartments and 1,301 hotel rooms, according to city housing documents.

City spokeswoman Sara Higgins said hotel units are also considered part of the available housing units because companies rent out multiple rooms and floors at some hotels during the week.

Not all have benefited from the oil boom in the area though. Local resident Marc McPeters moved to the area during the previous boom and has lived on the same plot of land for decades.

Back then, McPeters said she had to purchase her mobile home from New Mexico because housing was scarce.

Today, Endeavour Energy Resources operates an oil rig on almost half of McPeters’ property, but she said she doesn’t receive royalties from production revenue because Endeavour owns the mineral rights to her land. In Texas, land rights and mineral rights are sold separately.

When Endeavour approached her about drilling on her property, McPeters said she wasn’t aware that her property ownership didn’t include mineral rights, which would entitle her to royalty payments on any oil production on her land.

“How they got them, I don’t know,” McPeter said. “They paid me $8,500 to put that pump jack there, and I had to pay taxes on that. They said ‘This is what we’re going to give you. Get out of the way.’”

Employment

The boom has also resulted in the lowest unemployment levels in the state as new drilling corporations have set up shop offering thousands of new jobs for locals and field workers who have moved into the area. In February, the unemployment rate dropped to 3.2 percent for the Midland metropolitan area — the lowest rate in the state and one of the lowest in the nation — according to a monthly report by the Texas Workforce Commission. The state unemployment rate, which has increased slightly this year, is 6.5 percent.

Adam Chavez, field coordinator for EagleOne, an independent transportation company that does oilfield transportation, said he moved to Midland from Plainview in 2011 because of the work opportunities in the area.

Chavez, who started as a company driver and was on call 24/7, travels home to visit his family during the weekend but lives in one of multiple RV campgrounds that have emerged throughout the Permian Basin. Some RV parks rent out space to oil workers who sleep in tents on makeshift grounds that locals call “man camps.” Man camps are not permitted on System land, according to a University Lands official.

“I’ll be here as long as there is work and if the work doesn’t move north,” Chavez said. “I’ll be here until they say it’s dried up.”

Midland became the fastest-growing metropolitan area in the nation last year with a population increase of 4.6 percent, and Midland County was ranked as the 10th-fastest growing county, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

High employment opportunities in the oil fields have left local restaurants that offer lower-paying jobs struggling to staff their operations while demand increases.

In the last two years, Gerardo’s Casita, a local Mexican restaurant, has lost cooks and kitchen staff to the oil fields, forcing Jerry Morales, Midland City Council member and owner of the restaurant, to step into the kitchen almost four times a week.

Morales said his restaurant has benefitted from the boom with tables occupied from open to close every day as the community thrives economically, but he has also had to make changes to adapt to the staffing challenges that come along with an increased amount of patrons.

It’s not unusual to see managers and owners working hosting and busboy duties in other restaurants, Morales said.

“It’s been very hard for us in the retail business to compete with an industry where they’re working 80 hours overtime in a week at 22 years old, bringing home a $3,000 check,” Morales said. “I’m probably paying $2-3 more [an hour] than I was 24 months ago.”

Gerardo’s Casita now closes for three hours between lunch and dinner and is closed all day on Sunday because Morales said he doesn’t have the staff to cover sufficient shifts to avoid paying current employees overtime. The restaurant has also increased menu prices to make up for the increased wages.

“It took a little while for us to understand [the boom] and it took a little to see if it was really going to last,” Morales said. “I don’t really call it a problem. It’s just a challenge.”