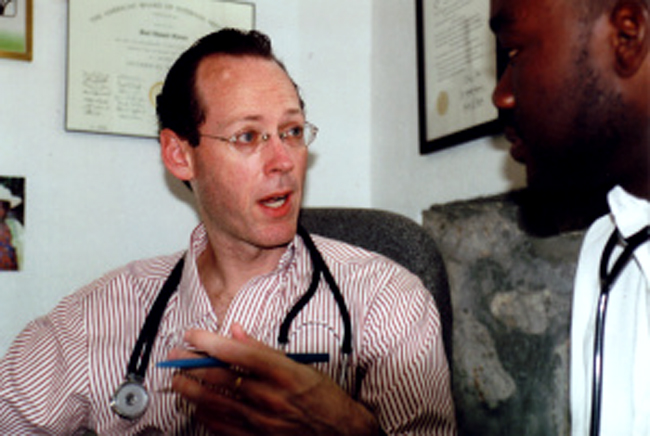

As the director of Partners in Health and United Nations Deputy Special Envoy for Haiti, Paul Farmer has a legacy of healing and activism that spans from Mexico to Russia. In celebration of his new book “To Repair the World,” the author and medical anthropologist will speak about his experiences as an international health advocate on Monday.

Farmer’s success in the realm of public health stems largely from his ardent convictions about medical treatment in general.

“The fight for health as a human right … has so far been plagued by failures,” Farmer said in an interview with National Public Radio in 2008. “Failure because ill-health, as we’ve learned again and again, is more often than not a symptom of poverty and violence and inequality. We do little to fight those when we provide just vaccines.”

The Partners in Health organization that Farmer co-founded in 1987 takes this idea a step further. According to the organization, medicine isn’t the solution to a country plagued by disease, malnutrition, violence and lack of infrastructure. The solution, they argue, is giving each community the tools necessary to combat poverty.

Among the Creole-speaking population of Haiti, “Dokte Paul” has attained somewhat of a celebrity status. Many other health care professionals had written off the Caribbean island as a lost cause, but Farmer saw an opportunity to reach out and bring advanced medical care to an undeveloped nation.

“The assumption that the only health care possible in rural Haiti was poor-quality health care — that was a failure of imagination,” Farmer writes in “To Repair the World.”

Farmer’s visit is part of a biannual lecture series hosted by the Humanities Institute and comes in the context of planning for UT’s new medical school. He currently holds a Ph.D. in anthropology and a degree in medicine from Harvard University.

According to Lynn Selby, a graduate student in the department of anthropology, Farmer works as a medical anthropologist examining the “social and cultural dimensions of illness, health and medicine,” and often advocating the idea of social justice.

For Deliana Garcia, director of the Austin-based Migrant Clinicians Network, Farmer’s humane and pragmatic model in Haiti and other countries has worked better than previous attempts.

“Context is everything to him,” Garcia said. “He can look at the human emotional piece, he can look at the programmatic piece, he can look at the dollar motivational piece, he can look at the absence of the science and he can hold all of those things simultaneously and still work toward solutions.”

Melissa Smith, a physician at the Seton McCarthy Community Health Center, is excited to see what impression Farmer will leave on UT students.

“We have an opportunity with the new Dell Medical School at UT-Austin to train new physician leaders to respond to the challenges of the 21st century,” Smith wrote in an email. “Dr. Farmer’s approach of working in partnership with communities, to focus on the root causes of health problems and to find innovative, cost-effective ways to provide high quality medical care, would transform medical education and ultimately, the health of our community.”