In almost exactly one month, the state of Texas will vote on one of the most important issues in its history. More important, certainly, than the much more publicized races for attorney general, lieutenant governor and even the governorship itself. Many Texans’ livelihoods and the continued prosperity of the state as a whole hang in the balance.

So no pressure.

The vote we are referring to is for a Texas constitutional amendment that would allocate $2.5 billion from the state government’s $12 billion rainy day fund toward funding major water management projects across the state. The measure was up for debate throughout the most recent regular legislative session, and shortly before the session closed the proposal to put the water plan to a statewide vote was raised and quickly approved.

The plan comes in response to the increasingly dire warnings from the Texas Water Development Board, a state agency that monitors the state’s water outlook, that soaring population growth and dwindling water resources presage a disastrous outcome.

According to the TWDB, if Texas does not invest around $53 billion dollars in water management over the next 50 years, its total unmet water needs by 2060 will be more than 800 billion gallons per year, or almost 15 times the amount the city of Austin used in 2009.

When considering those figures, it should be noted that the TWDB bases them on a hypothetical repeat of the “drought of record” of the 1950s, which was the worst in Texas’ recorded history. However, according to Austin Water Utility Director Greg Mezaros, the drought currently parching the state is already worse. “This is not your father’s drought, this is not even your grandfather’s drought,” Mezaros said while testifying to the Austin City Council on Thursday. “This is, in my opinion, the worst drought we’ve faced in Central Texas, ever.” Backing up his claim, the Lower Colorado River Authority forecasts that water levels of lakes Buchanan and Travis will drop below 31 percent in November, past which point this will officially be the drought of record.

Moreover, a study of tree-ring data by the director of UT’s Environmental Science Institute, Dr. Jay Banner, showed that “megadroughts” far harsher and worse than anything previously accounted for are actually regular occurrences in the state’s geologic record, and predicted that droughts harsher than that of the 1950s would happen at least once a decade after 2040.

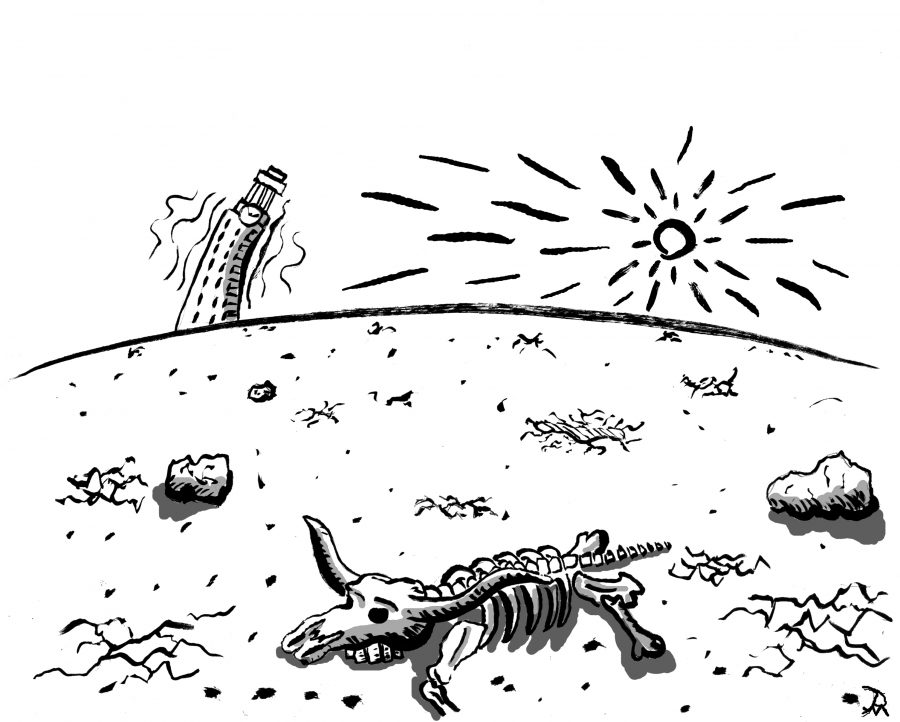

Needless to say, such an outcome would cripple the state’s agricultural sector, dry up its towns and cities and spell a certain end to the economic success Texas currently enjoys. At that point, the only way the state could reach anything resembling a sustainable equilibrium would be if most of its population packed up and left.

Texas Gov. Rick Perry and other officials, hoping to avoid that scenario, have spoken out in support of the water amendment and will do so more and more often as the vote approaches. “We stand at a historic crossroads, with a prime opportunity to meet our water needs for ourselves and generations of future Texans,” Perry said Wednesday in San Angelo, a city that is no stranger to water shortages.

We hope supporters of the amendment spend more time convincing the residents of Houston, which will have a disproportionately large impact on the vote. While this November is an off-year election for most of Texas, Houston also has a mayoral contest on the ballot as well as the continued fate of the Astrodome, and turnout is predicted to be much higher there. Thirty percent of the total votes cast in the state are expected to come from Harris County, double the usual figure. That means the wettest part of the state will have an especially large say in what happens to the driest.

It’s our opinion that the constitutional amendment up for a vote this fall, even with its 50-year outlook, is only a temporary measure to delay the inevitable disappearance of a finite resource. No matter how much money the state spends, it can’t change the climate or create water where there is none. It can only allocate existing resources more efficiently. There’s no changing the fact that water will determine the ceiling of Texas’ growth.

However, if the water plan doesn’t pass, farms will die, ranchers will be unable to feed their cattle, and towns will empty. Businesses will leave, unemployment will rise, and the point at which the state’s population will stop going up and start going down will arrive sooner rather than later.

We strongly support the passage of the water amendment, and hope Texas does the same. This state must do whatever it can to prepare itself for a much drier future.