Editor’s Note: This series explores personal and institutional responses to concussions, which have become an increasingly integral point of discussion surrounding football. Come back tomorrow for an in-depth look at the NCAA’s procedures in dealing with head injuries.

Stepping into an elevator oblivious to his surroundings, former UT football player Tre’ Newton pressed nine, and the door shut. As the button light flickered on and the elevator lurched upwards, his mind began to whirl.

One.

This will be the last time I talk to the media.

Two.

I’m not prepared for this moment.

Three.

There is no going back.

Four.

My teammates will be there watching me.

Five.

How can I stop? It’s the only thing I know.

Six.

What am I supposed to say?

Seven.

What will people say?

Eight.

Is this really the right decision?

The elevator flashed nine and as the doors opened, Newton strolled out of the elevator into Bellmont Hall on Nov. 15, 2010, for the last time as Tre’ Newton — football player.

During the next 30 minutes, that side of Newton would be cast aside. The son of an NFL player and a person who had identified himself almost singularly with the sport for a decade would voluntarily give up the sport he adores. It wasn’t because of an injury that robbed him of his speed or natural gift of strength. Instead, football raided his potential for long-term health after dealing him seven concussions in nine seasons.

With this in mind, Newton strode to the podium suddenly panicking about what to say.

He sat down and gazed out to a mass of cameras and somewhat familiar faces staring back at him. Newton, who had missed the team’s last game against Oklahoma State because of concussion symptoms, faced two rows of reporters anticipating his announcement.

A normally eloquent and heady speaker, Newton began with an unusual lack of grace, his words supplemented with a flurry of “ums”and “uhs.” But what he said resonated clearly.

“The best decision for me and my future is to not play football at the University of Texas,” Newton said. “I’m done playing.”

The kid who grew up in the Dallas Cowboys’ locker room, catching balls from Troy Aikman and shadowing his father Nate Newton, had taken one hit too many.

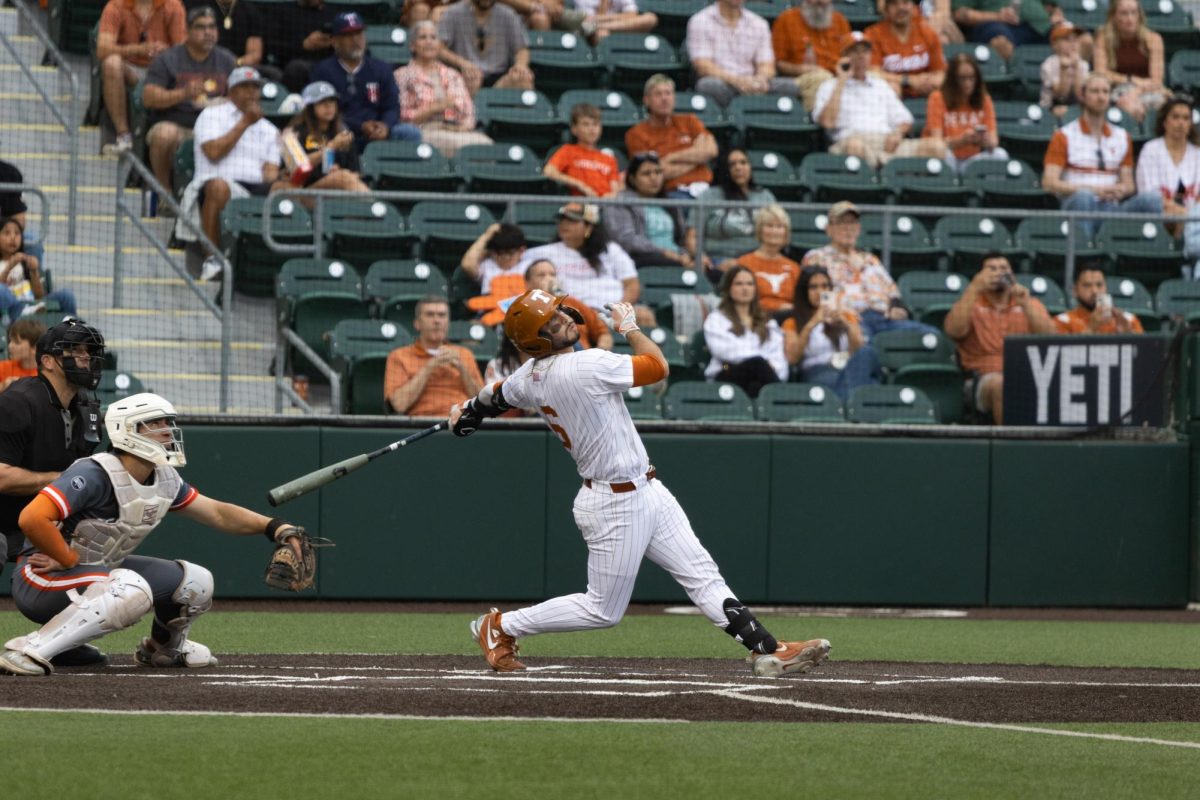

Daily Texan file photo from September 7, 2010. Photo Credit: Derek Stout.

It’s stories like Newton’s, as told by himself, his mother and his former teammates, that have sparked public interest into the issue of concussions in sport. The NFL settled a lawsuit with former players for $785 million in October of this year. High-profile documentaries such as “League of Denial” raise awareness and rule changes implemented by the NFL and FBS have attempted to curtail concussions. PBS, which began tracking the number of concussions in the NFL this season, already reports 102. Concussions and football are intertwined — players like Newton are caught in between.

Nathaniel “Tre’” Newton began playing football in the fourth grade, much to the chagrin of his father — a 318-pound offensive line behemoth with 14 years of experience in the NFL and six Pro Bowl berths — who did not want his son to strap on pads as a youth.

Despite this, Newton quickly flourished on the gridiron, combining natural genetic ability with a prescribed passion for the sport. Newton did not always exclusively play football, but he felt most at home between the hash marks.

He isn’t nearly as big as his dad, but he took his father’s quick feet and football knowledge to the field as a running back. There, he displayed speed and a taste for contact, running through people for years.

In sixth grade, Newton played running back for the Dragons, one of many youth football teams named after the eight-time 5A state champions, Carroll Senior High. Dressed in Southlake green during one game late in his final peewee season, Newton broke toward the sideline when an opponent snagged him from behind, pulled him around and slung him out of bounds. Newton’s head slammed against the track surrounding the outside of the field.

He staggered up and gingerly paced toward the sideline to tell the coach, his dad, that he felt woozy. Coach, caught up in the game, brushed him aside.

But the injury wasn’t a minor bruise on a sensitive sixth grader. Instead, it was the first concussion in a career defined by them.

He moved on to junior high football the next season and remained concussion free for a year. Then in a game in eighth grade, Newton, attempting to break a big run, was met by a defender who laid into him, torpedoing the crown of his helmet under Newton’s chin.

Everything went black.

Newton awoke in the hospital with no memory of the incident.

He returned to field the next year without a second thought as the starting running back on Carroll’s JV team. To Newton, his concussions weren’t a pattern — only a pair of brutal hits that resulted in unfortunate injuries.

But his parents were concerned.

They sent him to a neuro-specialist after each incident. Following the second concussion, the doctors recommended that if Newton suffered another he should give up football, an opinion his mom strongly supported. Concussions at such a young age are dangerous because the brain is sensitive. Repetitive damage will cause brain swelling and can be fatal.

His parents warned him. If he sustained another concussion, he had to quit football.

With three games remaining in the season, Newton’s nightmare soon transformed into a groggy reality. In a game against Denton Ryan High School, Newton tried to throw a block for a teammate down field, but he was caught unprepared and took a solid blow above the shoulders returning him to an all-too-familiar fuzzy state — his third concussion.

This couldn’t be brushed off as chance. He had been advised of the threat they posed too often.

So he did what any ninth grader would do — he cried.

Newton was not ready to be finished with the game, and his parents eventually relented.

As a sophomore, Newton excelled at the high school level, rushing for 1,345 yards and 13 touchdowns on 171 carries in his first varsity season. Even at 16, while quick, Newton preferred to plow through defenders.

Concussions seemed to be the only opponent he couldn’t shimmy past, let alone bruise through. He suffered his fourth career concussion in the same stadium he endured the previous one. He didn’t agonize after this injury, returning to the field three weeks later — head clear.

For the remainder of his sophomore season and high school career, his vision was pristine. Newton helped lead the Dragons to the 2005 5A State Championship title over Katy High School.

Newton rushed for 2,010 yards and 20 touchdowns as a junior, spearheading the Dragons’ offense to a second 5A state title. His senior season, Newton assisted a three-peat effort rushing for 1,373 yards and 16 touchdowns.

Newton committed to the University of Texas on Feb. 24, 2007. The injury that plagued him, and even terrified him in high school, could not be further from his mind.

This sense of security wouldn’t last long.

Continue to "Life after football, former Texas Longhorn Tre' Newton's road back, Pt. 2".

This article has been updated since its original posting.