Did you miss Part 1 of this story? Read it here.

Editor’s Note: This series explores personal and institutional responses to concussions, which have become an increasingly integral point of discussion surrounding football. Come back tomorrow for an in-depth look at the NCAA’s procedures in dealing with head injuries.

When the class of 2008 arrived at Texas, they were poked, prodded and measured at length by the Longhorn medical staff in an NFL combine-like atmosphere. Newton’s concussion history was no secret, and Texas’ doctors would handle him with care.

Still, Newton suffered his fifth concussion during a spring practice his freshman year, when he eventually redshirted.

His first year on the field was a culmination of everything he believed Texas football to be. He took the feature back role from Jamaal Charles, who left for the NFL as a junior, and helped lead the Longhorns to a 12-0 record, a Big 12 title and a national championship appearance. Newton rushed for 552 yards, six touchdowns and an average of 4.8 yards a carry.

But Newton suffered his sixth concussion in seven seasons during Texas’ fifth game of the year against Colorado University when Colt McCoy threw an interception. Newton raced back in pursuit of the ball carrier, but he was blindsided by a hit from a Buffalo blocker.

Newton’s symptoms following the hit were mild. Bright light, flashes on a television and loud noises bothered him. At times, his mind felt like it was stuck in quick sand. But the nausea and sharp headaches normally associated with concussions were absent. After missing one game, he played the remainder of the season without lingering issues.

Newton opened his sophomore year with three touchdowns in a 34-17 win over Rice University. But after the victory, Newton, like the Longhorns, began to slip. He averaged less than four yards a carry while Texas lost four of its next seven contests.

The Longhorns traveled to Kansas State at 4-4 the next week, hoping to turn around a horrendous start to the season. But in the first quarter, Newton suddenly had no idea what the play call was.

When the Longhorns huddled with the coordinators on the sidelines afterward, Newton asked fellow running back Fozzy Whittaker what he later termed as “stupid questions” about the play calls. Whittaker, worried about his teammate, told the trainers about the incident.

A few minutes later, team trainers peppered Newton with questions about the game. But he had no recollection of the contest to that point. Moments later he sat on the bench alone, head in hand.

Soon after, a trainer informed Newton of his concussion. Newton then ambled toward the locker room, oblivious to the 50,000 purple-clad fans yelling around him.

The following Monday, Newton was directed to the medical training staff’s office for what he thought would be a routine status checkup.

Instead, he was greeted with an unexpected question.

“Have you thought about your future in football?”

Newton wanted to blow the query off. Of course he wanted to play football. He couldn’t imagine a scenario in which he didn’t, but the doctor’s tone was too serious to ignore.

After a week of deliberation, Newton, still undecided, met with his parents.

“When is enough, enough?” his dad simply asked.

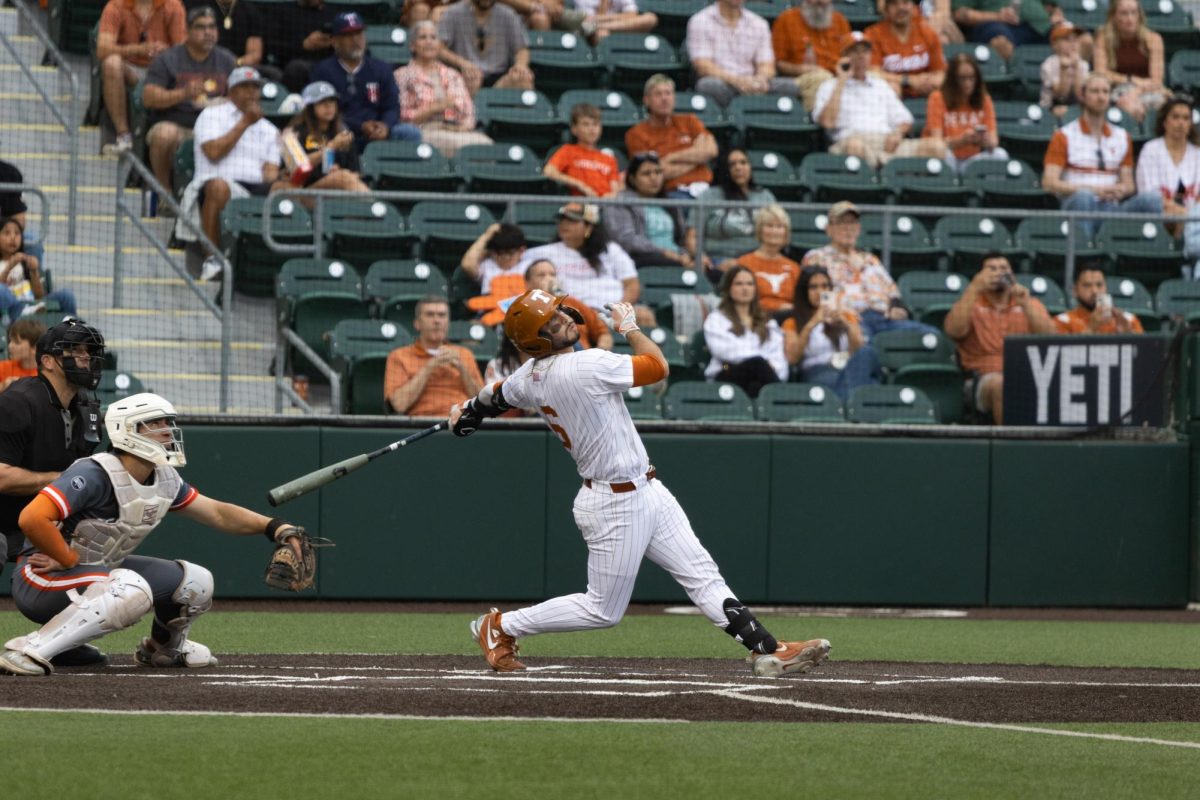

Photo Credit: Lauren Ussery | Daily Texan Staff

He asked Newton to consider the minor concussions he had gotten away with. Those are the incidents that accumulate, building slowly and finally exploding to the surface — leaving him with holes in his memory and a dull headache that took days, even weeks, to shake.

Then his mom, who had wanted him to quit football for a while, asked him to consider all of the people his health would affect and the burden he would become if he lost his memory or ability to function.

Many former collegiate and professional players suffer depression and, in serious cases, Alzheimer’s disease because of concussion-related symptoms. Other studies have shown that some former NFL players are left with symptoms of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy, a progressive degenerative disease of the brain.

A few hours later, Newton and his parents arrived at Darrell K Royal–Texas Memorial Stadium for a scheduled meeting with a team of doctors who laid out the possibility of his future and the risks that came with concussions.

Newton hesitated. He didn’t want to quit, but he knew himself better than anyone. If he didn’t quit now, he’d change his decision and play next season.

He decided to let go.

Newton answered questions from media members spinning his pronouncement as a positive, but he hated giving up the game.

His shocked teammates watched from across the room. Only a handful of players knew about Newton’s decision before the announcement.

Over the next two months, the Longhorns’ season spiraled toward a 5-7 finish, and Newton wanted no part. He missed football desperately, but being around the team resulted in a pain any number of concussions couldn’t have prepared him for.

He avoided his former brothers at all costs. When his roommate Blake Gideon invited him to hang out with the team, he’d make up excuses. After the injury, the Longhorns’ coaching staff offered him a student coaching job, but he politely declined. He would make small talk in classes with members of the team, but he avoided football with the same maneuvering he used on the field.

The pain and symptoms from the concussion subsided after a few weeks, but Newton was left to deal with the mental backlash of quitting something that had organized every aspect of his life.

Newton would go to class, do his homework and then stew, unaccustomed to free time. He filled the void with a video game binge. Marathon sessions of the NBA 2K basketball series served as an escape; his favorite game, Madden (NFL), was cast to the side.

The rebuilding process was slow. One morning early in the spring semester, Newton sought a routine and decided to begin working out once again, slogging with Longhorn trainers each day. But Newton scheduled his lifting sessions during practices and team meetings. He didn’t want to trick himself into believing football remained an option.

Newton eventually took up the student coaching position he had previously turned down. He didn’t start until the following fall, but he attacked the job with a renewed fervor. It wasn’t the same thrill as playing, but it was the closest he could find.

After the 2011 season, he graduated with a degree in corporate communication and decided to attend graduate school to pursue sports management.

Now 24 years old, Newton pushed forward at UT with a new goal in mind — to become an athletic director. Football is a sport he just can’t shake.

He now works full time with the Longhorn Foundation, helping raise money for Texas Athletics after interning with Texas Sports Information, Longhorn Network and Texas Athletics’ compliance department. He’s motivated, charging at his new goal with the same zeal he had when running for the goal line.

Newton’s experience provided context for his former roommate Jackson Jeffcoat, a player with a very similar upbringing. Both had NFL dads, majored in corporate communication and always had football dreams. Jeffcoat is a likely first-round pick in the 2014 NFL draft, but he faced a huge obstacle last season when he tore a pectoral muscle for the second-straight year.

One day late in the fall semester, Jeffcoat complained about the long rehab process to Newton, a friend for more than a decade.

Newton, as he’s done with other players, suggested Jeffcoat realize how lucky he was to still have football.

“Be happy you are playing football,” Jeffcoat said Newton told him. “Because anything can happen and it can be gone and taken away from me, the game I love, like it happened to him. He put it in perspective.”

Newton may not ever shed another block or quickly flip the ball to a referee after a touchdown, but he believes the qualities he’s gained fighting through adversity will serve him for decades.

Decades is the key word. There is no telling how Newton’s concussions will affect him in the future. For now, he’s symptom-free and living without the constant wooziness and confusion that shadowed him during his football career. The decision to quit early, foregoing further damage, limits the possibility that Newton will join the quickly expanding line of former collegiate and NFL players suffering from the long-term effects of concussions.

“I know I made the right decision,” Newton said. “The rate I was having concussions and the ones I was able to hide, it was definitely time to stop playing.”

Doubts still occasionally creep into Newton’s mind. He records every Texas game instead of viewing it live, because — what he credits to the coach within him — he still loves breaking down the team’s plays. But turning on the TV on a Sunday afternoon is still occasionally a trial for Newton, even three years later. Newton knows if a few things broke differently, he’d be a Sunday gladiator, too.

But he’s not angry at the game, and he doesn’t blame Texas or what some label the ambivalent nature surrounding concussions in football. Newton knows the sport he grew up with is violent, and there’s no way to change that.

A recent report from the Institute of Medicine on sport-related concussions in youth identified football’s “culture of resistance” as one of the biggest issues in addressing the issue of concussions in the sport. It’s a macho stigma that’s surrounded football from its roots.

Newton agrees football isn’t perfect, but says there is no way to completely prevent consistent injuries like his. It’s up to the players to know when they must let go.

Newton sits quietly in the Red McCombs Red Zone of DKR, only a few hundred yards away from the site of so many of his most memorable football moments.

He works, headphones in, on one of his final collegiate presentations, typing away, pushing through the bore for the reward of an “A,” just like he fought for tough yards and the satisfaction of a win. But in his quiet place, Newton is not left alone.

Every few minutes or so, a person strolls past him and waves. Newton responds in kind with an easy smile.

“Hey Tre’.”

“How’s it going Tre’?”

Almost everyone who ambled by, all Texas athletes far removed from Newton’s stint at running back, gave a friendly greeting.

He even gets a “Happy Birthday,” which he plans on celebrating over a quiet dinner with a friend. He realizes now that his decision of three years ago likely buys him a number of healthy birthdays to come.

Each time, Newton responded to the greeter by name, memory as sharp as ever.

Newton closes his laptop and walks away with sure strides.

With age comes perspective — Newton becomes more sure of this each day.

This article has been updated since its original posting.