Collecting art is more than a hobby or financial investment — personal collections often contain works by underrepresented artists. When diverse private collections are displayed in museums and galleries, they broaden people’s understanding of art history by providing access to works of various styles and backgrounds.

Local art collectors Rudolph Green and Joyce Christian collect African-American and African diaspora art. Pieces from their collection are currently on display at the Visual Arts Center and are open to the public until March 8. On Saturday, the center will host a symposium with guest lecturers who will discuss how to collect art and why collecting art affects art history.

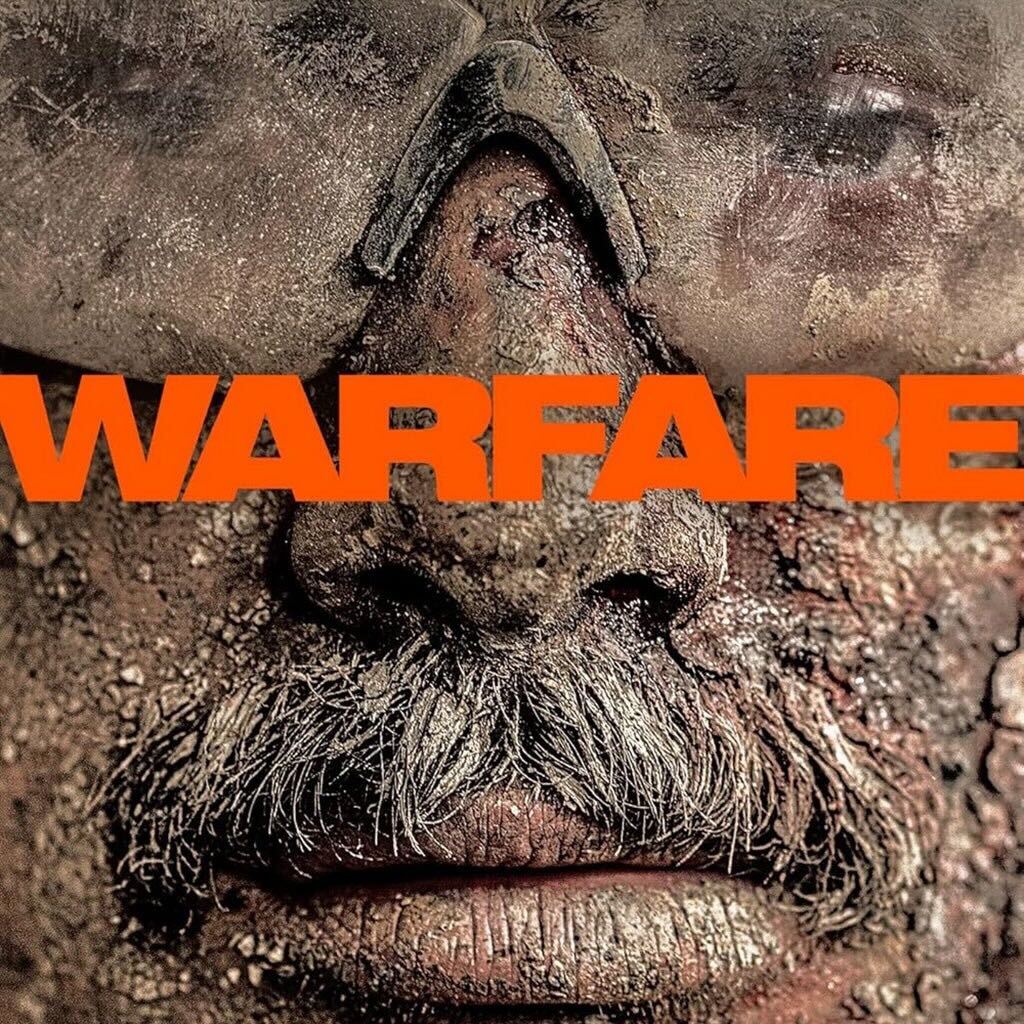

The Green-Christian Collection of Art of the Caribbean and African Diaspora consists of works spanning from the 1940s to the turn of the 21st century. The collection features artists from the U.S. and the Caribbean. Eddie Chambers, art and art history associate professor and the symposium’s organizer, explained that the portrayal of the artists and their communities in the media is a prominent subject in the exhibition.

“It reflects the images of people and artists themselves,” Chambers said. “That tends to be a wonderful manifestation of culture. It means a lot when an artist visualizes him or herself and their communities. You have artists who give explicit social narratives.”

Robin K. Williams, curatorial fellow and graduate student, said the collection is important because European artists dominate the mainstream art world, while African-American and African diaspora artists tend to be sidelined.

“It’s the problem with the way in which art history as a discipline was formed and how art has become historicized,” Williams said. “Art has always been produced by all kinds of people, so the collection is important for bringing those voices into the conversation because our culture is more pluralized, and it should be.”

Saturday’s symposium will host professors from around the country who will discuss their personal experiences as curators and scholars. Each speaker specializes in African-American or African diaspora art and will address the topic of how these kinds of collections help broaden the understanding of art history.

“The speakers are coming from different backgrounds, so they’re each offering a unique perspective on this broader topic,” Williams said. “It will be an interesting, lively lineup, with strong personalities and backgrounds in the area of collecting and thinking about art.”

Part of the goal of the symposium is to encourage people to consider art collecting as more than a hobby for rich people — anyone can begin to collect art, whether it’s posters or postcards. More serious art collectors often leave their collections to museums and galleries after they pass away, contributing to the kinds of art available to the public.

“In New York, the Schomburg Center grew out of one collection of one man,” Chambers said. “His library, art, artifacts, books — all that material is now the Schomburg Center and is now a major resource for so many subjects. So the ways in which individuals have this wonderful potential to make contributions above their own interest, that’s really what we’re exploiting here.”

The symposium will offer guests a comprehensive insight into Green and Christian’s collection, as well as information on how to explore art collecting for themselves.

“The key message or assertion of the symposium is that people should be encouraged to not be intimidated by the prospect of collecting and to know their contributions are going to make a difference and are going to be worthwhile,” Chambers said. “One can visit a graduate-degree show at a local school and buy the work of a student. There are all sorts of ways that each of us has the potential to make a contribution.”