Editor’s note: This is the first in a two-part series on blood donations. The second installment, which focuses on what happens to blood after it has been donated, will run in the paper tomorrow.

Doctors once treated sick patients by draining their blood until the patients became euphoric — and even then, the patients often died. Today, doctors rarely take blood from sick patients, except in small doses. Instead, the blood comes from healthy people — and only those who voluntarily give it up. The problem is that most people aren’t donating. While 38 percent of the country’s population is eligible to give blood, less than 10 percent actually do.

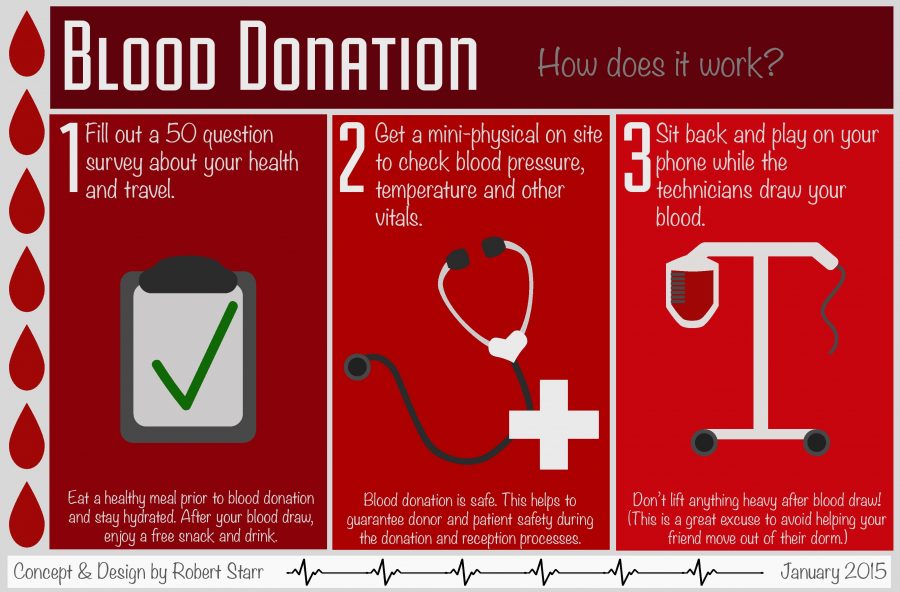

The basic eligibility requirements for donation are simple: Donors need to be in good health and weigh over 115 pounds. Anyone who meets the requirement can head on over to their local blood donation center. Once there, potential donors enter a small, private room to answer a short survey about their medical, travel and sexual histories.

“We’re asking questions that ensure you’re healthy enough to donate blood, as well as if your blood is safe to transfuse to a patient,” said Justine Garza, director of business development at The Blood Center of Central Texas.

These short, basic surveys aren’t without controversy. Gay and bisexual men — about one in six of whom are HIV-positive — cannot donate blood unless they have been celibate since before the original “Star Wars” movies came out.

This ban comes from the Food and Drug Administration, and not from the blood centers — and it was enacted in a time before there was a way to test blood for HIV. The FDA recently announced that it favors modifying this requirement, but it could take months or even years for any change to take effect.

Answering “yes” to certain questions may prompt follow-ups from the doctor, but few answers automatically prevent someone from donating. Donors are allowed to have tattoos and piercings, for instance, as long as the body modifications were administered using sterile equipment or more than one year ago.

Once donors have gone through the questionnaire, they’re given a mini-physical. During the examination, the donors will have their pulse, temperature and blood pressure checked. They will also receive a finger-stick to determine their red blood cell count.

After this preliminary screening process, donors move to the blood donation room, where they lie in a bed. They can read, make conversation or Snapchat with friends while a trained phlebotomist — a person who draws blood — does all the work. The whole process is completely safe and only takes about an hour. Garza recommends donors share any fears they may have with the technicians ahead of time.

“Donors should let their phlebotomist know that they’re really nervous about [the process],” Garza said. “That’s really helpful for the person that’s drawing their blood to know. They can help them through that.”

After the donation, the donor walks to a room in the back of the blood center to eat cookies, drink juice and relax for a few minutes until they feel comfortable walking out on their own. After a brief respite, they’re encouraged to eat a good meal, stay hydrated and avoid heavy lifting and alcohol.

And that’s it: This basic process is all a donor has to do to save up to three lives.

“Everybody has it; everybody needs it; why not share?” said Cindy Rowe, public relations manager for the blood center.