Editor’s note: This is the second in a two-part series on blood donations. The first installment focused on what happens during the blood donation process. The second focuses on what happens to blood after it has been donated.

It only takes five to 10 minutes for a trained medical professional to draw a pint of someone’s blood for donation. However, once the blood’s in the bag, it still has a long way to go before it can be given to a recipient.

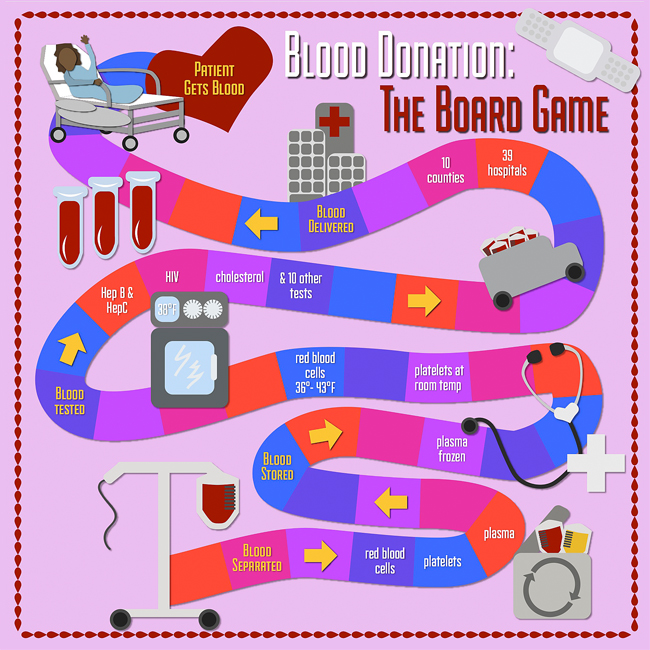

After the blood is drawn, it is separated into individual components — red blood cells, platelets and plasma — all of which have different shelf lives.

Plasma lasts the longest of the three components: a full year. Red blood cells can go six weeks without expiring. Platelets, which must remain at room temperature, are more likely to harbor bacterial growth and can only last five days.

It takes six to 10 blood donations to generate enough platelets for a recipient, so centers encourage direct platelet donations. During a two-hour platelet donation, blood from a donor’s arm passes through a machine where a centrifuge removes platelets. The machine then returns the blood into the patient’s arm. With this technology, a healthy individual can provide up to 24 platelet donations every year.

During either donation process, the technician draws an additional three vials of blood — which sounds like a lot — but isn’t even enough to fill a shot glass. These vials go to a separate facility where they undergo 14 tests. One of them is a cholesterol test so that frequent donors can keep tabs on their levels. Other tests check for blood compatibility, as well as for sicknesses such as syphilis, hepatitis and the big one — HIV.

These tests reduce the risk of transmitting these illnesses down to practically zero. There are 30 million transfusions per year, and the last time one resulted in a confirmed transmission of HIV was in 2008. In this case, a donor had only recently become infected, and the level of HIV antibodies in his system was too low to detect. He also had anonymous sexual encounters with both men and women outside his marriage and lied about them during the donor screening process.

While hospitals sometimes know they are going to need blood in advance — such as in planned surgeries — the center mostly provides blood for the unexpected, such as automobile accidents.

In the unfortunate and rare case that blood expires before finding a proper host, medical companies can use the blood to test equipment they are developing. Very little blood is wasted.

The bigger concern is blood shortages, as it is hard for hospitals to anticipate when there will be a high demand. When a tragedy occurs, it’s easy to convince people to donate, but those donations take several days to process and can’t be used right away. Hospitals need blood in anticipation of the disaster — not afterward.

For this reason, it is best for eligible donors to make giving blood a habit. If you are in good health and weigh more than 115 pounds, consider donating a pint yourself today.