In elementary school, UT doctoral student Christina Gonzalez’s biggest worry wasn’t making friends in her new class — it was getting through her next word.

“I first became aware of my stutter when I was six years old and at a new school,” Gonzalez said. “It was my peers and teacher who made me cognizant of the way I speak differently. As I grew up, my parents’ concern [for my speech] and their efforts to put me in therapy [made] it a ‘thing’ in my consciousness; that I had to make stuttering something I had to overcome.”

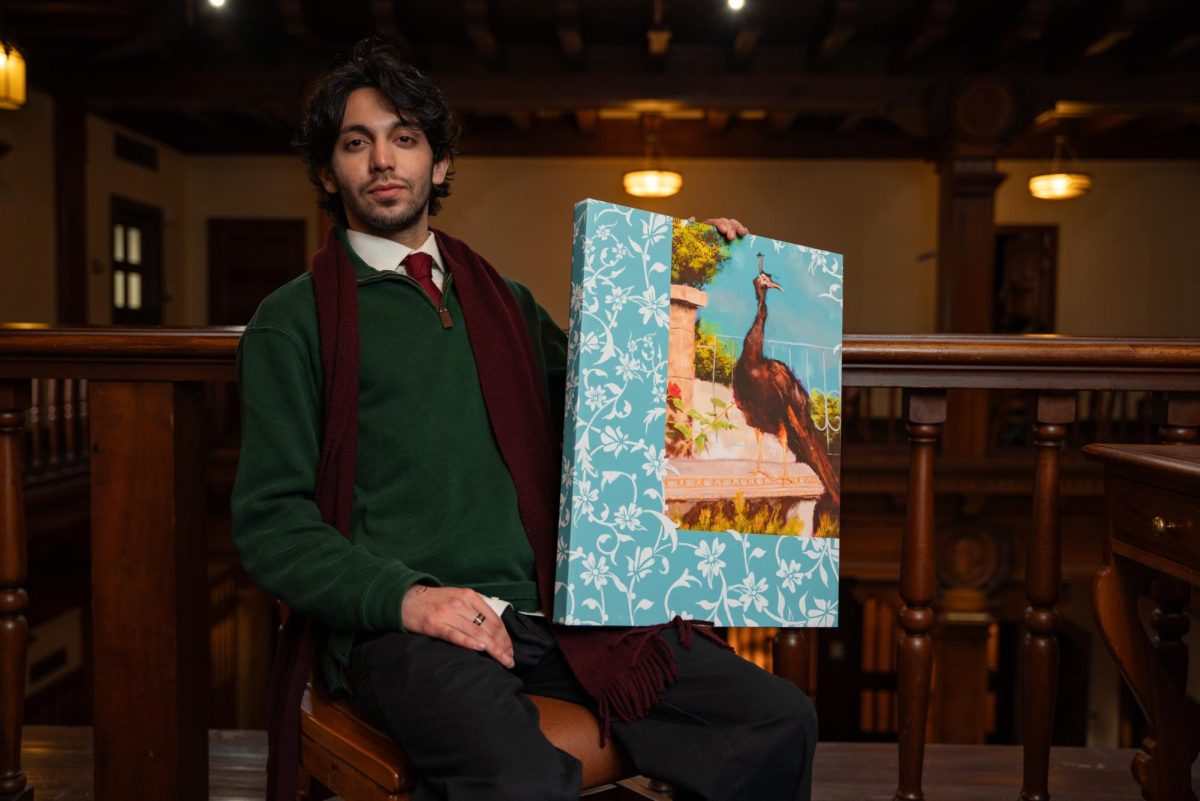

Gonzalez, a third-year anthropology doctoral student, said she continues to stutter and at times struggles with it. Her speech has commonly generated uncomfortable looks and uneasiness from her listeners, common responses that she said she has gotten used to and is no longer bothered by.

While in college, Gonzalez said she has sometimes felt the stress of the feeling that she might not always be able to effortlessly convey her thoughts.

“It’s an anxiety-ridden experience to move through a university for a person who stutters, especially the higher up you go because there’s this expectation about what an 'expert' looks like,” Gonzalez said.

Gonzalez recently began attending the Lang Stuttering Institute, a nonprofit research and treatment center at UT that aims to help people who stutter. Patients regularly participate in group discussions and present speeches to their counterparts.

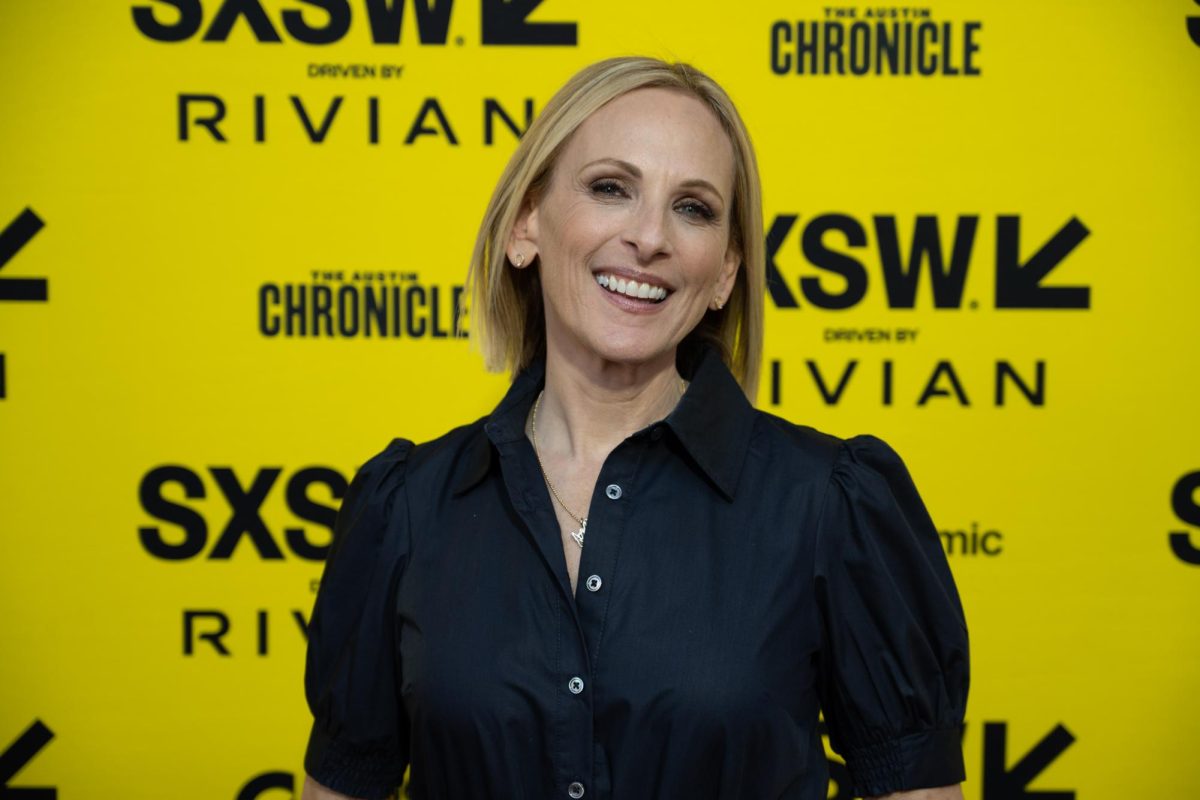

Stuttering is widely thought to be curable or reversible. Courtney Byrd, the Lang Stuttering Institute director and UT associate professor, said media that depicts stuttering as a largely treatable problem, such as in the film “The King’s Speech,” have it all wrong.

“Stuttering is neurophysiological in nature,” Byrd said. “The notion that there is a cure is a fallacy, and a common one. [The institute] can help young kids who stutter. We can get them to reach a level of fluency where you listen to them and you would not hear someone who stutters. However, as you get older and you have less neuroplasticity, it’s more challenging to create a foundation of fluency.”

The Lang Stuttering Institute is able to primarily carry out its mission through volunteer efforts. Aside from Byrd and another professor, the institute is essentially run through student leaders from a variety of majors.

“Stuttering isn’t just about speech pathology,” Byrd said. “It’s about something we all struggle with. It’s about communicating and connecting with others and expressing our thoughts without having the fear of being judged. This role entrapment and all these stereotypes and false perceptions that continue to be pervasive will no longer exist, and that it will start here, because of the efforts of our students.”

Gonzalez, who is interested in being a professor after graduate school, said she aspires to continue to do and study what she loves, living life without apprehension about how listeners might perceive her speech. She said she wants to be understood.

“This is the way I speak,” Gonzalez said. “At the end of the day, I want to be a better communicator. But it’s not just about speech. It’s about self-knowledge, self-awareness and self-mastery. I hope I can help push against any sort of preconceived notions and stereotypes, not only of what a stutterer looks like or is but also of what a person who is accomplished in academia looks like and is.”

This article has been updated since publication.