Berdanier is a philosophy junior from Boulder, Colorado. She is a senior columnist. Follow her on Twitter @eberdanier.

UT is set to lead a consortium of research institutions in a five-year study on alcoholism and how the disease changes the brain. This is exciting news, but sadly its importance has been overshadowed as focus has been drawn increasingly to national politics and away from issues that directly affect students. While this research brings national attention to UT, it should also draw campuswide attention to the very real issue of alcoholism.

Typically, alcoholics are portrayed in the media in one of two ways. The first is as the degenerate, underperforming drunk whose disease serves to hinder the lives of those around him and is never cured. The second is the high-functioning alcoholic, who typically works as a lawyer or a doctor and whose disease is never seen as the problem it is.

In the media, however, college-aged adults are never portrayed as alcoholics, thus causing actual college students to believe they could never be categorized as such.

In college, binge drinking is a large part of the party culture that prevails across campuses nationwide. Because all drinking is portrayed as harmless, this too is viewed as just another part of the party culture. But it shouldn’t be. Binge drinking in college can hurt your grades, and even lead to a future dependence on alcohol, increasing your risk for developing alcoholism.

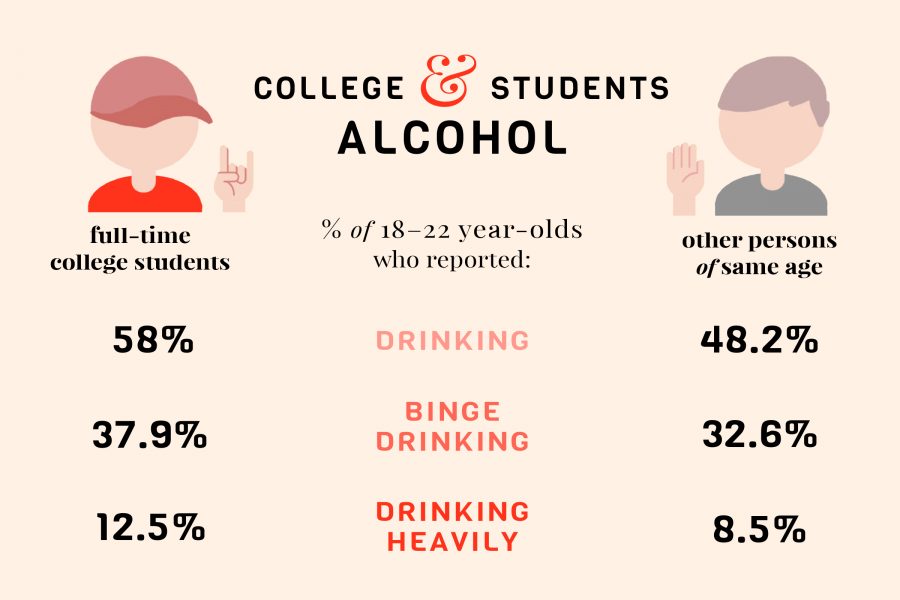

A reported 37.9 percent of college students engage in binge drinking, higher than the rate of non-college students of the same age group. Yet we don’t view these behaviors as dangerous. Instead they’re accepted, and almost expected of college students. We’re supposed to go out to fraternity parties, drink too much and black out on our 21st birthdays. All these behaviors are viewed as normal, almost a rite of passage into college life.

About 20 percent of college students meet the criteria for Alcohol Use Disorder, otherwise known as alcoholism. The prevalence of drinking in college doesn’t come without consequences. And since the topic isn’t widely discussed on campuses, it leads to a stigma being placed on those who do have drinking problems. Discussion about the research we’re conducting on alcoholism could easily lead to destigmatizing the disease on our campus.

With UT leading a $29 million series of studies on alcoholism and its effects on the brain, we have the perfect opportunity to bring the topic into general discussion. UT needs to do more than the brief online course it requires freshmen to take. It must bring the issue into broad discussion, especially among upperclassmen, with whom drinking is a more rampant and available pastime. Alcoholism is more than just adults who have lost their way, it begins with college students lost in a party culture.