For more than six years, law professor Ariel Dulitzky would pack up his things and head out after office hours — not to go home and relax, but to begin work on his second job as one of five representatives on the United Nations Human Rights Council‘s Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances.

Dulitzky studied kidnappings and enforced disappearances as the U.N. representative for Latin America and the Caribbean from 2010 to this year. He spent the maximum amount of time an appointed expert can spend — two three-year terms — and was elected chair of the group from 2013 to 2015.

The native Argentinian completed his final term in the spring, but he continues to transfer the lessons he learned as a U.N. representative to his law students in the Human Rights Clinic and published a report with them on kidnappings in Mexico last month.

“Positive change takes time, and in human rights, positive change even takes longer,” Dulitzky said. “And it’s very easy to destroy achievement in a second, and it’s very, very difficult to reconstruct those achievements once they are destroyed. So we need to be very, very aware of how to protect what we achieve.”

For years, Dulitzky persisted on a mission that may seem thankless to others; it was unpaid work with a slim chance of closing a case. Dulitzky said since the creation of the council in 1980, representatives have only been able to solve or receive information on about 20 percent of over 55,000 cases.

Dulitzky said his main role as representative was to serve as a channel of communication between grieving families, government and other organizations as well as provide emotional support.

“Imagine that your husband disappears and you don’t know what happened, you don’t know if that person is alive or dead,” Dulitzky said. “Your anguish is really bad. Mental health support is very, very important.”

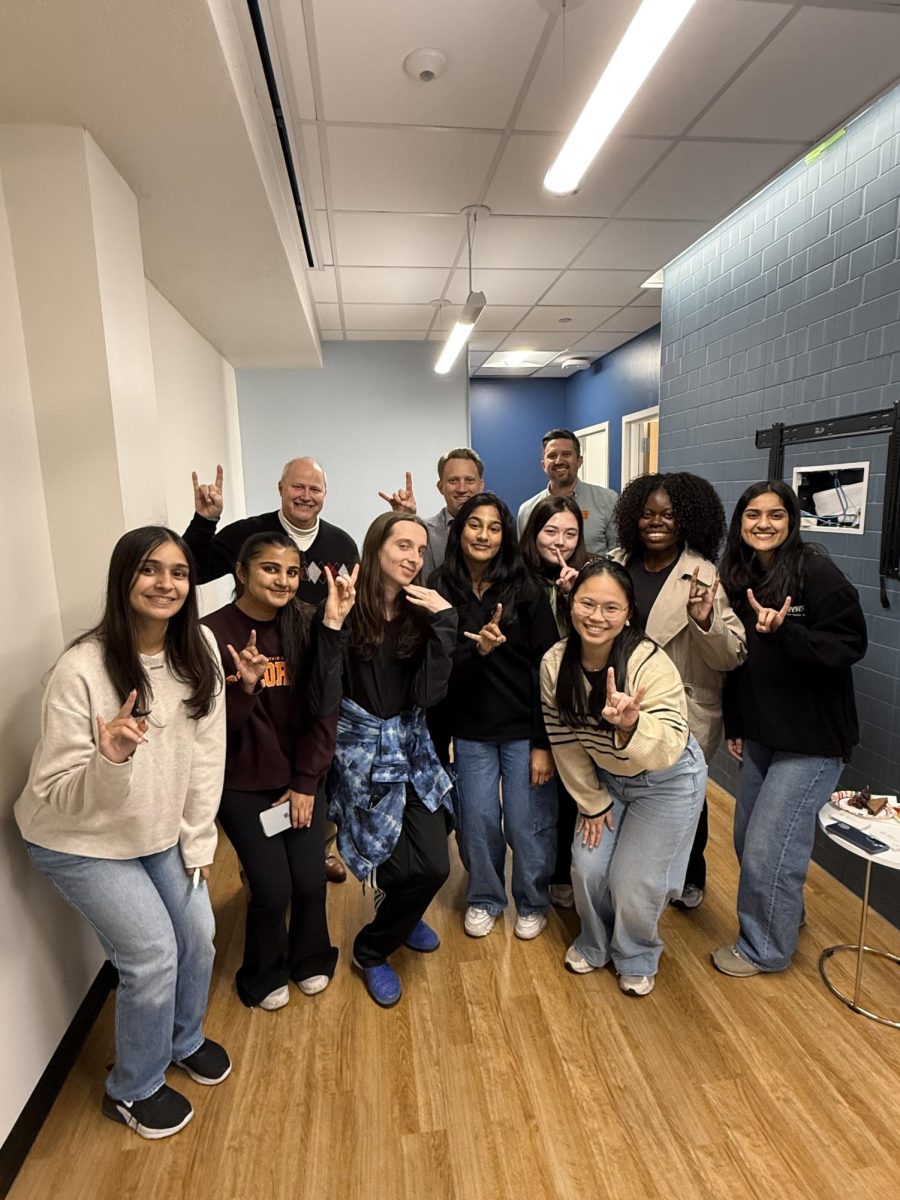

In recent years, Dulitzky brought his work with him to UT to his clinic students. Last month, they released a report on Zeta drug cartel kidnappings in Mexico. Dulitzky and his students spent three semesters studying testimonies and found patterns in the speech, including some implicating Texans in providing weapons to the cartel members.

Moravia de la O, graduate student in Latin American studies and social work, said working on the report was challenging and sometimes stressful when reading testimonies of extreme violence, but also a great learning experience.

“For me, working on this project really highlighted the powerful impact that academia can have to addressing and challenging social injustice, whether that be in Texas, in Austin or internationally,” de la O said.

Clinic administrator Ted Magee said by going through actual trial testimonies, students built real-life skills in researching an important issue related to the violation of people’s rights in Mexico.

“All the clinics exist to give law students practical skills with either law or advocacy … beyond what they learn in class,” Magee said.

After years working with the U.N., Dulitzky said his main takeaway is that slowing down is not an option.

“As a human rights defender, as a human rights scholar, I need to keep going,” Dulitzky said. “I need to keep trying. I need to keep thinking and devising more effective ways to protect human rights.”