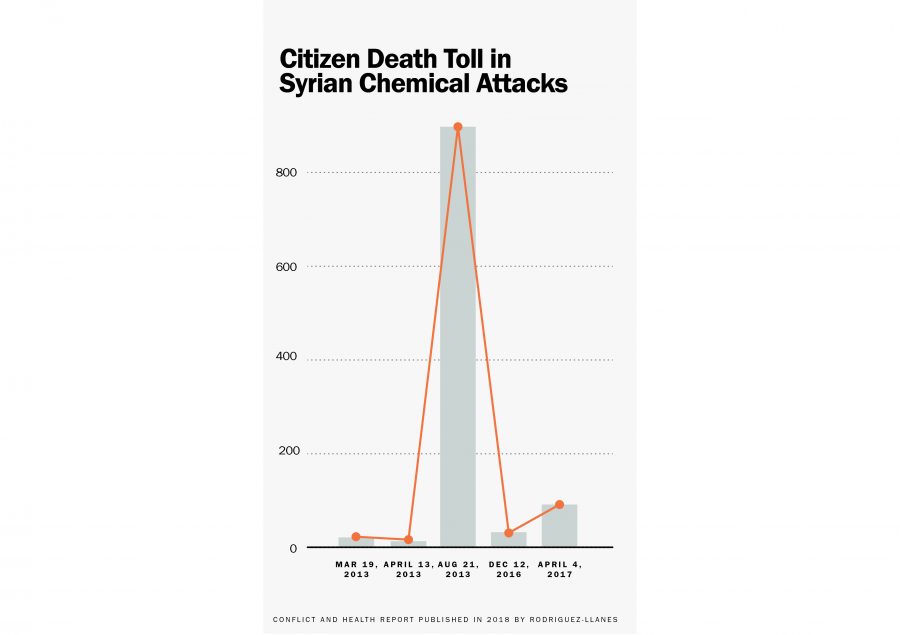

A wave of colorless, odorless and toxic gas spread over the Eastern Ghouta region in August 2013. It was one of many chemical attacks of the Syrian Civil War, contributing to the mounting death count in the region, according to The Washington Post.

Current technologies lag in tracking the spread of dangerous chemicals, but researchers from UT San Antonio are developing numerical models with the power to provide near real-time tracking of communities facing chemical attacks. This development was only possible through the help of Stampede2, the flagship supercomputer at UT Austin’s Texas Advanced Computing Center.

Previous models for predicting the spread of airborne chemicals had calculation times upwards of four hours. But the improved model, developed by UT San Antonio mechanical engineering associate professor Kiran Bhaganagar and her team, has cut that time down to 30 minutes, Bhaganagar said. Bhaganagar added that she hopes to eventually make it 10.

“Syria is one of the cases where there was so much fatality in just one small incident, and that’s extremely worrisome,” Bhaganagar said. “And these are chemicals that can easily be obtained everywhere. This is a problem we already knew how to tackle, we just needed to do it.”

The current challenge comes from inaccurate hand-held sensors that don’t give enough data for predictions, Bhaganagar said. That’s why their team from the Laboratory of Turbulence Sensing and Intelligence Systems turned to mobile sensors.

Researcher Sudheer Bhimireddy monitored how chemicals in the air behave. He compared actual data with data produced by the model to gauge accuracy of predictions.

“Databases like these will help to narrow down the model accuracy,” Bhimireddy said. “But, as timescales (in tracking chemicals) decrease, I need much better information on local weather conditions. That’s where the mobile sensors come in.”

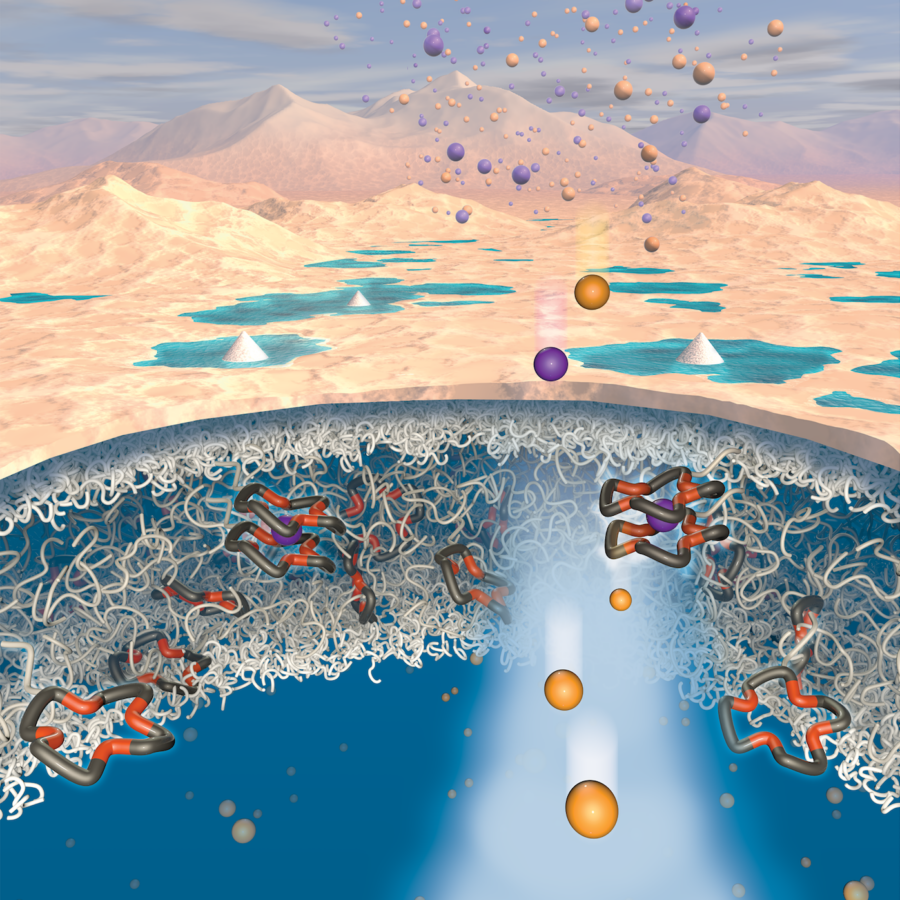

Using reports from the Syrian attacks, the team was able to test the accuracy of the model by inputting local weather conditions. Bhaganagar said the mobile sensors cost only a few hundred dollars and stand on tripods to measure a variety of factors. Time of day, seasons and location all play an important role in predicting which way airborne chemicals spread, according to Bhimireddy. The most important factor in determining where a chemical will travel is turbulence, an element which is key in determining the direction wind will travel.

“Take a cup of coffee and add sugar,” Bhaganagar said. “You mix sugar in the coffee, and after some time you just have a sweet liquid. That’s exactly what turbulance does. It creates a homogeneous medium for air.”

None of these calculations would be possible without the help of UT-Austin, though, Bhaganagar said. She added that normal computers can’t handle the amount of data needed to quickly predict where and how chemical attacks will travel. Other computers will often take weeks to compute the information UT’s supercomputer Stampede2 can process, such as pinpointed weather data, in under an hour.

“Their (UT-Austin) resources are very valuable because in order to test all these things, we need to have that supercomputer,” Bhaganagar said. “Otherwise this would just be a hypothesis. For some of these models we would need 20 days on other computers, but now we don’t.”