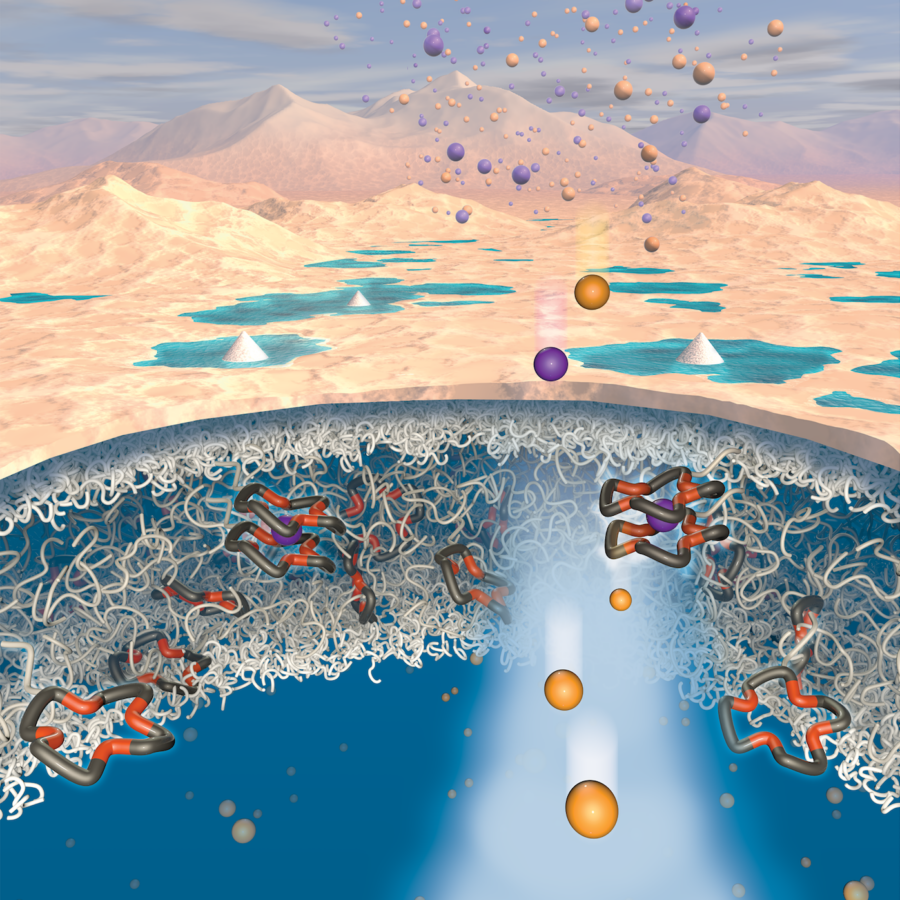

A shift in how Austin houses source their electricity is key to reducing carbon emissions in residential areas of Austin, UT researchers found.

Currently, many houses are set up to receive energy directly from natural gas. But if houses receive their energy from power plants, any type of energy source can be used, paving the way for a switch to renewable resources. The process of heating our homes from electric plants instead of directly through natural gas pipelines is called electrification.

Benjamin Leibowicz, researcher and assistant professor of engineering, said direct natural gas consumption in residential areas of Austin is responsible for 14 percent of the city’s carbon emissions. Additionally, UT-Austin is responsible for 3,742,528 thousand cubic feet of natural gas usage in 2017, which is lower than previous years according to UT-Austin’s Utilities and Energy Management department.

In addition to better construction practices, Leibowicz and earth and energy resources member Christopher Lanham, among others, evaluated the use of cleaner energy sources and more efficient appliances. They evaluated each to figure out which combination of strategies would be the most effective in reducing carbon emissions.

“The dominant trend was towards electrification and electrifying those building services,” Leibowicz said. “More efficient buildings save money in terms of energy in a lot of different ways because buildings require less energy for heating and cooling. And certain appliances are cost-effective to switch devices, like light bulbs.”

Electrification involves transitioning a household’s energy supply from carbon-producing sources, such as natural gas, to electric power plants. While electricity production may not be clean, it gives buildings the opportunity to continue to decarbonize by providing the infrastructure to switch to renewable resources, which helps in the long-term, according to Leibowicz.

“A key point is that it’s important to consider long-term emission targets before investing in strategies that might be helpful for reducing emissions in the short-term,” Leibowicz said. “It’s possible that in the short-term, using natural gas for heating could reduce emissions and be cost-effective, but this strategy would limit the ability to decarbonize the system more significantly in the long-term.”

Eliminating the direct consumption of fossil fuels by residential buildings would almost be impossible in the long-term due to the structure of buildings, Leibowicz said. He also said buildings relying on natural gas are hard to decarbonize without replacing the whole building.

Leibowicz added that Austin’s use of natural gas is smaller than that of cities in colder climates because our peak energy consumption has a shorter duration. According to the Institute of Physics, heating systems are also more energy-demanding than cooling systems.

“It really depends on how quickly we want to decarbonize,” Leibowicz said. “In Austin, natural gas consumption in the residential sector is smaller than in colder climates.”

Leibowicz said these findings apply to both consumers and city government. Residents can invest in energy-efficient appliances. Additionally, the City of Austin can make more strides to be green. Coupling initiatives with higher level policies such as carbon taxes or decarbonized building codes can also be powerful, Leibowicz said.

“What really matters is when you save energy,” Leibowicz said. “The Texas peak in energy usage is in middle of the year, and peak A/C demand goes down with increased insulation in buildings. Ultimately, it’s not only how much energy you save, it’s also when you save it.”