Virtual spiders may actually be beneficial to those who fear the eight-legged arachnids.

In a recent study, UT psychology researchers teamed up with the UT3D program to develop an immersive, 3D video exposure-based therapy for arachnophobia, or the fear of spiders. By the end of the treatment, people were more willing to approach a live spider, and a questionnaire showed their ratings for fear of spiders decreased, said Emily Carl, a UT clinical psychology graduate student who helped analyze the results of the study.

Exposure-based therapies work by exposing a patient to the feared object, situation or event in a safe environment in order to break a pattern of avoidance and safety behaviors such as touching spiders while only wearing gloves, Carl said.

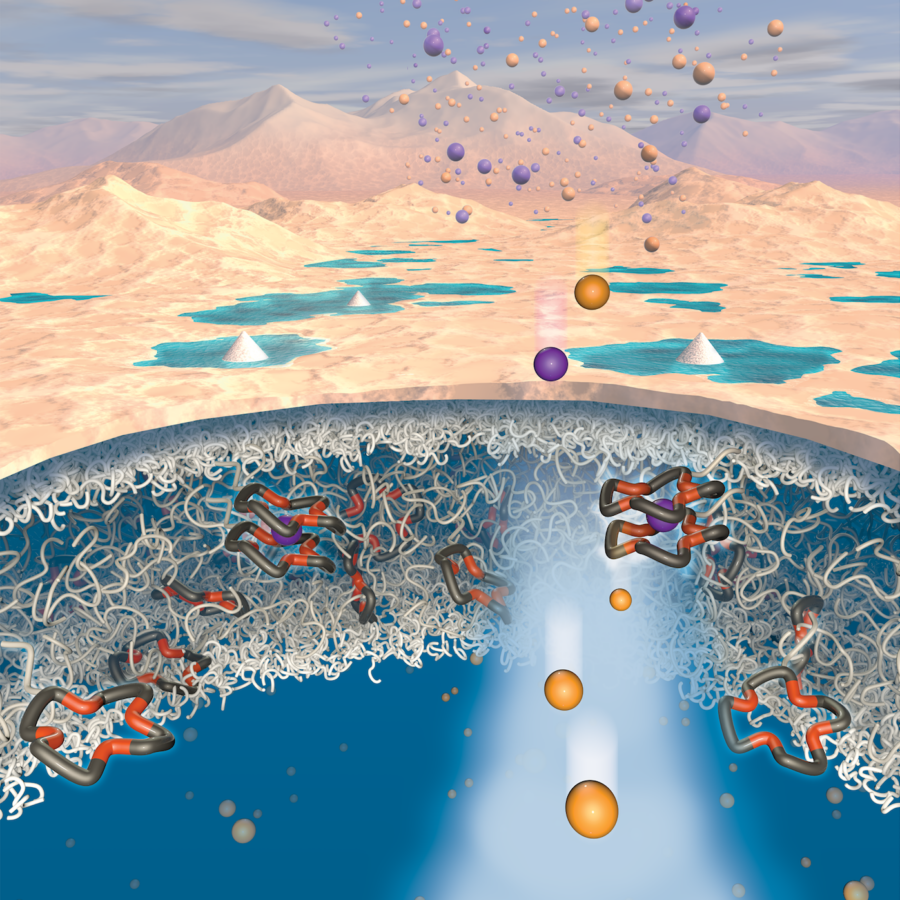

For the study, participants who exhibited a strong fear of spiders were shown five minute videos of a live, Chilean rose hair tarantula through a virtual reality headset.

The footage included a spider crawling towards the camera to create a looming sensation and the 3D-effect made it seem as if the spider was directly coming towards the participant, according to the study.

The videos were filmed by the UT3D department using stereoscopy technology.

Stereoscopic 3D video works by tricking the brain into perceiving 2D images as if they were 3D, said the study’s lead researcher Sean Minns, UT radio-television-film graduate and current clinical psychology graduate student at Columbia University.

“You have two images — one image in one eye, one image in the other — that are close enough together but just slightly apart, that when looked at, your brain connects them and creates this sense of depth,” said Minns.

Minns also said this technology can be used to make exposure-based therapies more effective in treating phobias.

“Prior research shows that exposure therapy works incredibly well when you can take the patient and put them in front of what they’re afraid of,” said Minns. “The issue is that a lot of the time, the patient either isn’t willing to face the phobic stimuli in-person or it’s not logistically feasible.”

By using immersive stereoscopic 3D video-based treatments, patients can practice exposing themselves to the feelings of encountering a spider in real life, Minns said.

“During the study, when the spider was approaching the participant, it activated a splurry of front detection systems in the brain,” said Minns. “By getting people to activate these, it allows them to be more efficiently habituated to those sensations and to get through those fears in a situation that’s safe for them.”

Carl said stereoscopic 3D videos may even be a better alternative to more expensive computer generated imagery based treatments.

“If the CGI is not well-developed, it can end up looking cheesy like a nintendo-like spider,” said Carl. “In this case, we actually had footage of real spiders taken. It was less time-intensive, less expensive to develop and you don’t have to worry about it not looking real enough.”

With rapidly advancing technology allowing it to become cheaper to develop immersive 3D videos, Minns said he hopes this will encourage researchers and filmmakers to work together to create these new types of therapies.

“My hope is that this will give researchers the confidence to get in contact with whatever film program is in their city and create these collaborative projects where art and science can merge together to create new treatment platforms for patients,” Minns said.