Editor’s Note: This is the fourth installment of The Texan’s series “Raising Voices,” which highlights issues of diversity at UT. Stories are produced in partnership with UT’s chapters of Asian American Journalists Association, National Association of Black Journalists, National Association of Hispanic Journalists and the National Lesbian Gay

Journalists Association.

Everyone knows senior chemistry Jackson Reyna is an avid scientist — it’s an inherent part of who he is. But for 20 years, no one knew an equally important part of Reyna: he is transgender.

“I just couldn’t take it anymore,” Reyna said. “It’s just so difficult keeping that inside, and there just comes a point where people start to question. You just have to let it out and be honest or forever hold your peace.”

When Reyna came out his third year of college, he was working closely with Kate Biberdorf, associate professor of chemistry, both as a teaching assistant and as a volunteer for the Fun With Chemistry program. Reyna said she was an important part of his coming out process.

“The first person I told who was affiliated with UT was Dr. B (Biberdorf),” Reyna said. “She was amazingly supportive and switched names and pronouns the very minute that I told her.”

Reyna said he received support from his inner circle, but the response from the larger scientific community was not quite as warm.

“It’s been a lot of misgendering, and despite correcting people over and over again, they’re still like, ‘No, I’m still going to say what I want,’” Reyna said. “I’m also a racial minority, so being a minority and LGBT is kind of difficult because you don’t have any kind of upper hand in authority.”

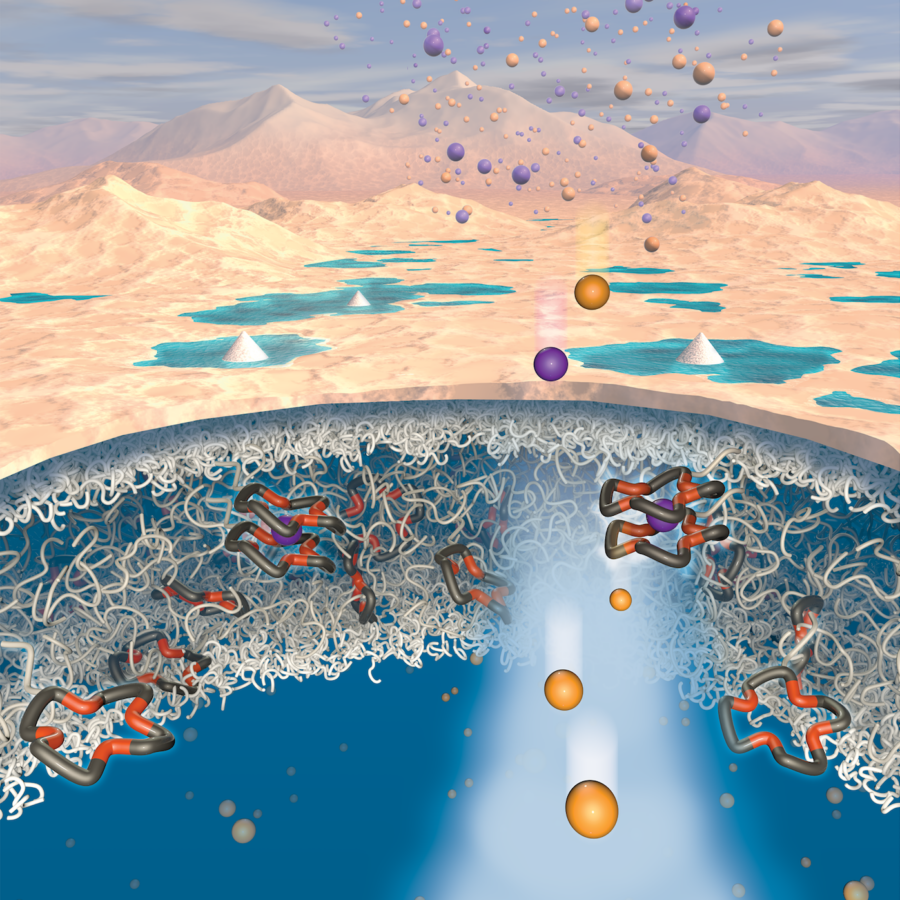

In science, individual identity often takes a backseat to research and objective data, Reyna said. This phenomenon was explored in a 2015 study published by researchers from California State University and the University of Minnesota.

The study revealed that STEM professionals tend to assume “neutrality” or remain indifferent in situations of inequality, resulting in the lack of attention to gender and sexuality issues. This behavior contributes to the invisibility and exclusion of many identities in science, technology, engineering and math fields, according to the study.

This neutrality can be attributed to science’s historical lack of diversity, said Stephen Russell, professor of human development and family science and chair of the College of Natural Science Diversity and Inclusion Committee.

“In some other fields, like the liberal arts or social sciences, people can actually see themselves reflected in the text of their scholarly endeavors, and they’re more likely to be around people like (themselves),” Russell said. “The possibility here for the College of Natural Sciences is to think about ways that STEM fields can be places where you can see yourself — to imagine what it means to be yourself in science.”

It was exactly this lack of representation that Reyna said motivated him and Biberdorf to launch S.T.E.M. oUT, an LGBTQ outreach program for the chemistry department, in spring 2017.

“Our main goal is to give LGBT representation in STEM while providing a safe place for discussion for allies to come in, ask questions and talk about things that they would be scared to talk about normally with other people,” Reyna said.

One of S.T.E.M. oUT’s main initiatives is allyship training. The Human Rights Campaign defines an ally as anyone who supports the LGBTQ community.

S.T.E.M. oUT conducts allyship training through live presentations that seek to create an open environment for LGBTQ students in STEM fields while also involving exciting chemistry demonstrations, Reyna said.

“In lab, if someone’s (transgender), everyone defaults to the ‘normal’ use of pronouns, and no one asks,” Reyna said. “We’ve designed (the presentation) to keep it entertaining while also being informative because it’s really about getting all of these scientists to be allies to these LGBTQ+ people.”

Reyna said he believes the presentations, which were given to all first-year College of Natural Sciences graduate students this year, have made an impact.

“My analytical chemistry graduate student is a first year, and, on the first day of lab, she asked us all to write our names and pronouns down on a sheet of paper,” Reyna said. “If she was at the presentation, then score, because that means we’re changing something.”

The importance of correct pronouns was explored by Russell in a study he published earlier this year. He found the use of correct pronouns was associated with dramatic differences in mental health for transgender adolescents, including decreased risks of depression and suicide.

“What that translates for the University is we should figure out how to check our assumptions based on our perceptions of gender expressions and figure out ways to be proactive about acknowledging people the way they want to be understood in this world,” Russell said.

Just as important as using correct pronouns is having strong and supportive mentorship from faculty and staff, Reyna said.

“It (mentorship) gave me a purpose: to be here with Fun With Chemistry rather than just going through the motions of going to class everyday,” Reyna said.

Today, Reyna said he feels more empowered than ever knowing that there are allies around him. Still, he said diversity in STEM fields must be encouraged and amplified.

“Diversity in STEM is important because people from different walks of life have different experiences and view the world differently,” Reyna said. “I want to see more representation. I want more people to be open about being themselves. Just because you’re in a science class doesn’t mean you’re losing your identity.”