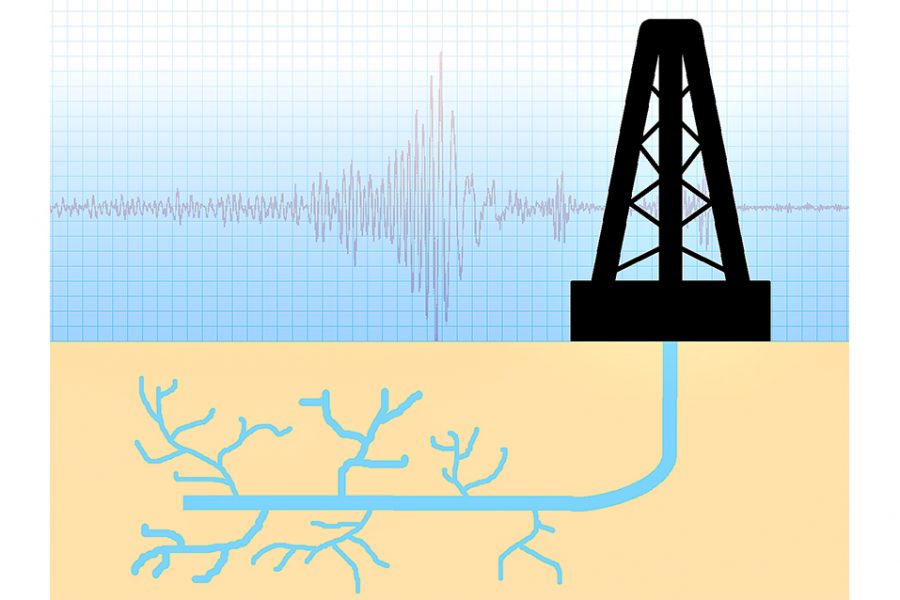

UT research revealed that excess water produced from hydraulic fracturing, a method used to extract natural resources such as oil by injecting pressurized liquid into rocks, can disrupt pressure levels underground and lead to earthquakes, according to a journal in the Seismological Research letters published on Oct. 31.

Researchers examined places where water was stored near tight oil fields including Oklahoma, Bakken, Eagle Ford and the Permian Basin shale field. Oklahoma had the highest levels of induced seismicity, with 56 percent of wells used to dispose produced water associated with earthquakes, according to the study. Eagle Ford Shale in South Texas came in second place, where 20 percent were associated with earthquakes.

Bridget Scanlon, lead author of the study and hydrogeologist, said Oklahoma was an exceptional study area because water was disposed near the basement, an area below sedimentary material.

“We were interested in determining why we see so much seismicity in Oklahoma,” Scanlon said. “The results of our analysis is that produced water is disposed in shallow zones in each of the other plays, whereas in Oklahoma, it was mostly disposed near the basement in deep wells.”

The findings revealed there were three factors — proximity to the basement , produced water injection rates and cumulative water volume — that led to minor earthquakes as a result of fracking, Scanlon said.

“Some previous studies emphasize injection rates alone or the distance from the basement alone,” Scanlon said. “But when we analyzed the data from Oklahoma, we found that all three factors are important.”

Scanlon said the research began when the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, a nonprofit that funds STEM research, asked her team to take a look at water issues related to seismicity, or frequency levels of earthquakes in Oklahoma.

“If we’re trying to manage produced water from oil and gas to minimize earthquakes, we need to understand what the relationship is between how we’ve been managing the water and what we’ve seen in terms of seismicity,” Scanlon said.

When water is stored in deep geologic formations, as is the case with Oklahoma, it can be easier to trigger earthquakes, because these formations are connected to faults underground, Scanlon said.

When oil and gas is extracted, water is usually injected back into the reservoir, which helps to stabilize pressure within it. Hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, cannot do this because the rock pores are too small for the water to be injected back, resulting in the water being injected into nearby geologic formations. This can increase pressure on the surrounding rocks, Scanlon said.

In 2015, the Oklahoma Corporation Commission reduced produced water injection rates and regional injection volumes by 40 percent in deep wells to mitigate seismicity, according to the study. The study also found that these changes resulted in a 70 percent reduction in the number of earthquakes over a 3.0 magnitude in 2017 compared with 2015.

Kyle Murray, co-author of the study and adjunct professor at the University of Oklahoma, said this estimation indicates that water disposal management is a potential way to mitigate earthquakes.

“The findings are consistent with the actions taken by the Oklahoma Corporation Commission to mitigate seismicity,” Murray said.

Scanlon said that for mitigating of earthquakes in Texas, they use the TexNet Seismic Monitoring Program to continue to study the effects of fracking.