Students, staff and faculty are working toward improving the University’s Title IX policies to better inform the University community about Senate Bill 212 and further support survivors.

Adriana Alicea-Rodriguez, UT associate vice president and Title IX coordinator, said the University’s Title IX Office’s SB 212 committee is currently reviewing the draft of SB 212 rules and enforcement as determined by the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board. SB 212 imposes criminal charges and job termination against faculty and staff who do not report Title IX violations promptly or who make false reports.

“(The) SB 212 committee is looking at all of the policies in place that could be impacted by this law and reviewing those to develop the implementation plan to make sure all campus community members are aware of the new reporting requirements,” Alicea-Rodriguez said.

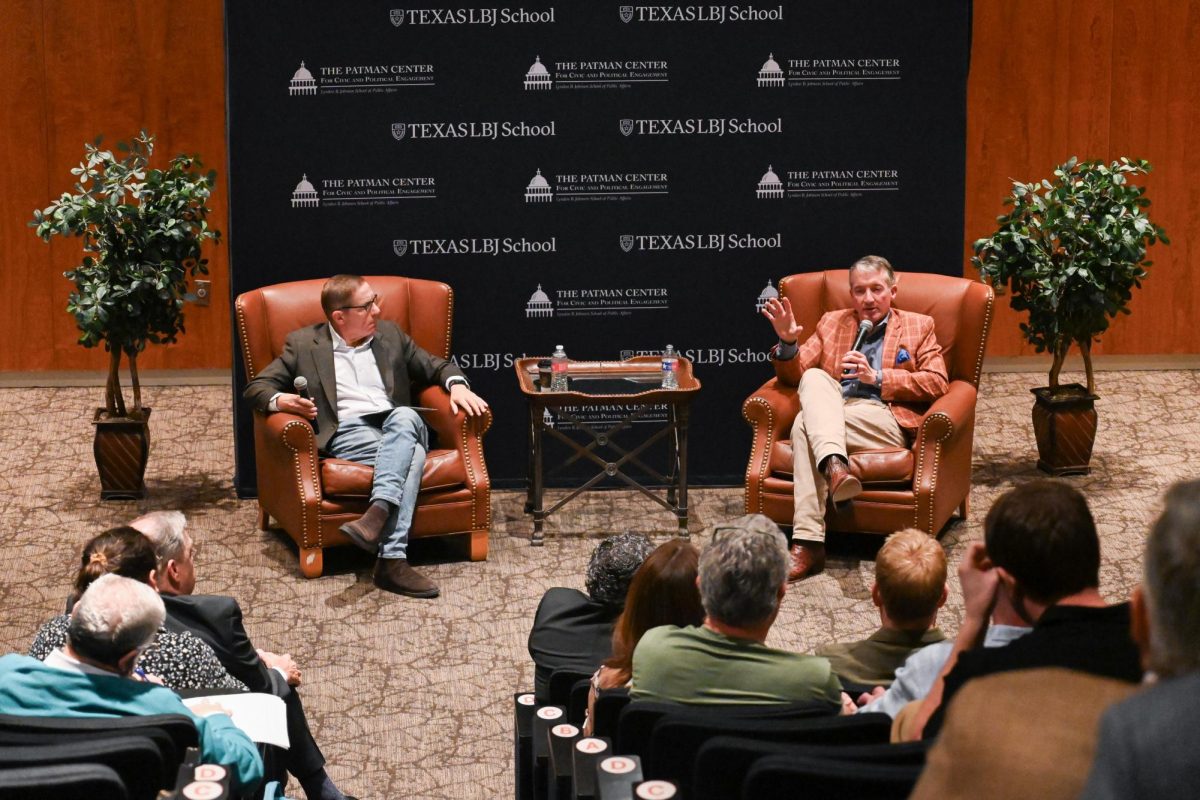

Faculty Council chair elect Brian Evans said he is working with Alicea-Rodriguez to create a Title IX training session for students and another for staff and faculty on SB 212, which will be enforced Jan.1. Title IX is the federal law banning discrimination on the basis of sex at any institutions receiving federal financial assistance.

“Title IX training is best done by a whole department,” engineering foundation professor Evans said. “The way we’ve been doing it at the University is, you just sign up for it if you want to, but you really need to retrain an entire academic unit. That’s how you change the culture.”

Alicea-Rodriguez said while there has been a spike in the number of daily Title IX reports made by faculty and staff since Sept. 1 in comparison to last year, she could not provide data or say it is only because of SB 212.

Delaney Davis, president of the sexual assault prevention student organization It’s on Us, said the organization is working on a bill with the UT Senate of College Councils that would require professors to disclose they are mandatory reporters on their syllabi beginning in Spring 2020. She said the bill would help students understand that if they share information that could be a Title IX violation, the professors are obligated to report it.

“The more information that we put out there about faculty and staff members being mandatory reporters, the better it is for students,” Alicea-Rodriguez said. “I’m always going to be in favor of anything that puts the information more out there so that we can reach out to more people.”

During roundtables hosted by It’s on Us this semester, Davis said many students complained about the length of formal Title IX investigations. She said investigations can take up to nine months, and many students said they do not get periodic updates about their case.

“It’s an already traumatic situation for someone who’s been sexually assaulted, and to have it take a super long time makes it even worse,” said Davis, a government and Spanish junior. “That’s almost a year’s worth of school where you’re dealing with an investigation where, by nature, you have to relive your trauma a little bit because due process is provided for the respondent as well.”