College athletes have long gone without pay for their talents, but new NCAA rules will give student-athletes opportunities to profit from their names, images and likenesses.

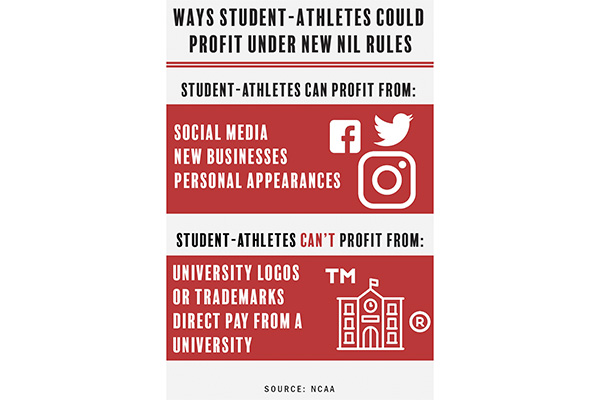

Name, image and likeness comprise an individual’s “right of publicity,” which allows control over the commercial use of one’s identity. NCAA officials voted unanimously in October 2019 to begin altering the organization’s rule that bars student-athletes from profiting off their names, images and likenesses to ensure collegiate athletes have equal opportunities as other students to make money. The NCAA Board of Governors approved new rules on April 28 that would allow student-athlete compensation through avenues such as social media that wouldn’t involve universities or their trademarks. Many wonder what the full rules will entail, with the NCAA’s three divisions expected to enact them in January 2021.

UT wouldn’t pay Texas senior quarterback Sam Ehlinger or junior center Charli Collier to play under new name, image and likeness rules, but they could potentially earn thousands of dollars on social media, according to data published by Axios from Opendorse, a platform that builds athlete brands.

“Students who have already established a great brand from the beginning will enjoy this,” Collier said via text. “Our name associated with the school brings money and attention, so why can’t we do the same as student-athletes without using the University’s name?”

New name, image and likeness rules could allow less-visible athletes to seek outside employment, said Tolga Ozyurtcu, an assistant professor of instruction in the Department of Kinesiology and Health Education.

“Our imaginations are like, we’re going to see Sam (Ehlinger) … selling SUVs on TV, but it also means … walk-on rowers who give the school 50 hours a week … can go get a job,” Ozyurtcu said.

Current NCAA compliance rules bar student-athletes from external employment, unless their university, another institution or private organization hires them as a counselor at a clinic or camp upon the NCAA’s approval, or the student-athlete starts their own business without using their “name, photograph, appearance or athletics reputation” to promote it. The rule book lists several employment caveats and exceptions, in addition to these exemptions.

“The model of amateurism cannot be upheld, according to them, if athletes are being paid for their performance — even if their employment is explicitly not related to their athletic performance,” said Markell Braxton-Johnson, a sports management graduate student, in an email.

Critics worry athlete compensation might eliminate integrity from college sports, but many athletes who might benefit most from their names, images and likenesses attend universities to meet professional league requirements, said Nick Phynn, a 2017 UT track alumnus.

“Are they really at the school for an education?” Phynn said. “I don’t think we’re changing integrity because these athletes are going to move on if they have the chance.”

Others argue scholarships and educational opportunities suffice, but Phynn said his scholarship didn’t cover all his expenses, and the 98% of athletes whose careers end after college don’t always enjoy promised benefits, as they leave universities with little real-world experience after investing all their time in sports.

Those who are not student-athletes can pursue endless endeavors, from creating startups to joining bands, Ozyurtcu said. He said modifications to name, image and likeness rules would give collegiate athletes the same freedoms.

“When it comes to the athletes, … we’re paternalistic,” Ozyurtcu said. “We want to ‘take care’ of them. What if we just treated them like adults and let them make decisions?”